Course

Understanding Lupus Nephritis

Course Highlights

- In this Understanding Lupus Nephritis course, we will learn about the prevalence and epidemiology of lupus nephritis among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

- You’ll also learn how to recognize the presentation of a patient with lupus nephritis.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of interprofessional team strategies for improving care and outcomes in patients with lupus nephritis.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 2

Course By:

Abbie Schmitt

RN, MSN

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

A lupus diagnosis and the complications that arise can be devastating for patients. Nurses are often looked to for support and answers, so it is important to educate ourselves on these serious conditions. Lupus nephritis (LN) is considered one of the most severe organ manifestations of the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Essential knowledge on lupus nephritis includes the defining features, epidemiology, pathophysiology of normal kidney function and lupus nephritis, clinical presentation, and treatments.

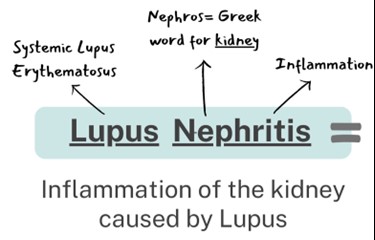

Lupus Nephritis

Lupus nephritis (LN) is an organ manifestation of the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The cause of lupus erythematosus is not known. Researchers suggest a genetic predisposition, but a genetic link has not been identified (2). This is a difficult reality, as patients and healthcare providers usually hope for a why. We will discuss the definition, prevalence, pathophysiology, manifestations, clinical diagnosis guidelines, and treatment regimens for LN.

Definition

Lupus nephritis (LN) is considered a condition and a manifestation. LN is one of the most severe organ manifestations of the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). LN is a form of glomerulonephritis, which is inflammation of the glomeruli (the tiny filters within the kidneys). This inflammation causes significant imbalances within the body due to impaired kidney function.

Overview of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by a loss of immune tolerance of endogenous nuclear material, which leads to systemic autoimmunity that may cause damage to various tissues and organs (1). Essentially, the damage to DNA structures causes the body’s immune system to be incidentally programmed to attack its own tissue. There are two types of lupus: systemic lupus erythematosus and “discoid” lupus erythematosus. SLE is systemic, meaning it can affect almost any organ system or tissue and presents in different manifestations impacting the skin, joints, kidneys, and brain (2). “Discoid” lupus erythematosus only affects the skin tissue. Our focus will be on systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) as we gain a deeper understanding of lupus nephritis.

The causes of SLE are unknown but many attribute it to genetic, environmental, and hormonal factors. SLE is hard to diagnose because the symptoms are often mistaken for those of other conditions. There is no cure for SLE, but symptoms can be managed. SLE presentation and prognosis are highly variable, with symptoms ranging from minimal to life-threatening. Patients with lupus may experience periods of exacerbation of symptoms, sometimes called ‘flares’, as well as periods of remission. SLE is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly caused by renal and cardiovascular disease and infections. LN is considered one of the most severe manifestations of SLE.

SLE can be compared to a guard dog intended to protect your home. The guard dog (immune system) protects you from unwanted intruders (infection), but also bites friends, family, and the mailman (your own organ tissue)!

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you cared for a patient with autoimmune disorders impacting the skin or joints?

- Are you familiar with other autoimmune conditions?

- How are systemic and focal conditions different?

- Can you list the two types of lupus?

Epidemiology and Statistical Evidence of Lupus Nephritis

Systemic lupus erythematosus has an estimated prevalence of about 10–150 per 100,000 persons (2). However, a large number of people could be undiagnosed due to being asymptomatic or the symptoms mistaken for other diseases. An average of 40% of SLE patients develop lupus nephritis (LN). Those diagnosed with SLE at a younger age are at a higher risk of developing LN and other complications (1).

SLE in general is more prevalent in women, especially women of reproductive age, than in men; the ratio is 9:1 (1). Therefore, 90% of SLE cases are women. However, men who have been diagnosed with SLE more commonly develop LN than women with SLE. Numerous studies have also found that the prevalence of LN in patients with SLE is higher in African American, Hispanic, and Asian populations (1). The impact of SLE disproportionately affects children and adults living in poorer geographic areas (8).

Within 10 years of the initial SLE diagnosis, 5–20% of patients with LN develop end-stage kidney disease and the multiple comorbidities associated with immunosuppressive treatment (1). Mortality in LN is quite variable ranging in between 15% and 25% (6). It is important to remember that the treatments are also very risky because it is difficult to balance the risks and benefits of suppressing the immune system. LN is a topic of significant research, so nurses can have a meaningful impact in raising awareness and encouraging hope for more advanced treatment development.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you name the population at greatest risk for developing SLE?

- Do you think all ethnicities are impacted equally?

- Do you think men and women are impacted equally when developing SLE and LN?

- Have you ever cared for a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus? If so, what were specific problems they faced?

Normal Kidney Function

The kidneys have several life-sustaining functions. The kidney serves to maintain fluid and chemical homeostasis and to contribute to hemodynamic stability (3). The renal tubules of the kidneys have unique and vital roles. Daily urine output is about 1–2 L, and over 98% of the glomerular filtrate is reabsorbed by the renal tubules (3).

There is a delicate balance and interdependency between the kidneys and other organs. For example, the kidneys produce hormones that help regulate blood pressure and control calcium metabolism, the kidneys also release a hormone that stimulates red blood cell production. A simple and fun mnemonic formula to help you remember the vital functions: A WET BED.

A WET BED: Functions of the Kidneys

A - controlling ACID-base balance

W - controlling WATER balance

E - maintaining ELECTROLYTE balance

T - removing TOXINS and waste products from the body

B - controlling BLOOD PRESSURE

E - producing the hormone ERYTHROPOIETIN

D - activating vitamin D

Controlling acid-base balance

- Our bodies always have a state of delicate equilibrium among the acids and bases, which has a parameter known as pH.

- The kidneys excrete or retain acids and bases when there is an excess or lack of them.

- The normal pH of the blood is 7.35 to 7.45.

Controlling water balance

The kidneys regulate the volume of urine produced and adapt to one’s hydration level to maintain water balance.

Maintaining electrolyte balance

The kidneys filter specific electrolytes from the blood, return them back into circulation, and excrete excess electrolytes into the urine. Kidneys maintain electrolyte balances like sodium and phosphate.

Removing toxins and waste products from the body

The kidneys remove water-soluble waste products and toxins and excrete them in urine.

Controlling blood pressure

The kidneys produce an enzyme called renin, which converts the angiotensinogen produced in the liver into angiotensin I, that is later converted in the lungs into angiotensin II. Angiotensin II constricts the blood vessels and increases blood pressure. Another way the kidneys help reduce elevated blood pressure is they produce more urine to reduce the volume of liquid circulating in the body to compensate.

Producing the hormone erythropoietin

The kidneys produce a hormone called erythropoietin, which aids in the creation of more red blood cells (erythrocytes), which are vital for the transport of oxygen throughout all the tissues and organs.

Activating vitamin D

The kidneys transform calcifediol into calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are ways to help remember the major functions of the kidneys?

- How do the kidneys regulate and maintain electrolyte balance?

- Can you list examples of how electrolyte imbalances affect various organ functions? (example: cardiovascular system)

- What are some ways the kidneys help to regulate blood pressure?

Anatomy and Physiology of the Kidneys

It is important to review the anatomy and physiology of the kidneys. The urinary system as a whole is composed of two kidneys, a pair of ureters, a bladder, and a urethra. The kidneys are located at the back of the abdominal wall and at the beginning of the urinary system. The size of each kidney is dependent on age, sex, and height, but the average length is approximately 10–12 cm, and the right kidney may be slightly smaller than the left kidney (3). The kidneys are made up of nephrons, which are microscopic structures composed of a renal corpuscle and a renal tubule.

The average human kidney is composed of approximately one million individual functioning nephrons, each containing a single glomerulus or filtering unit (3). The function of filtration is accomplished by three major components of nephron activity: (1) glomerular filtration, (2) tubular reabsorption, and (3) tubular secretion. These components respond to factors including renal blood flow, neuroendocrine effects, and the fluid and nutrient supply to the body.

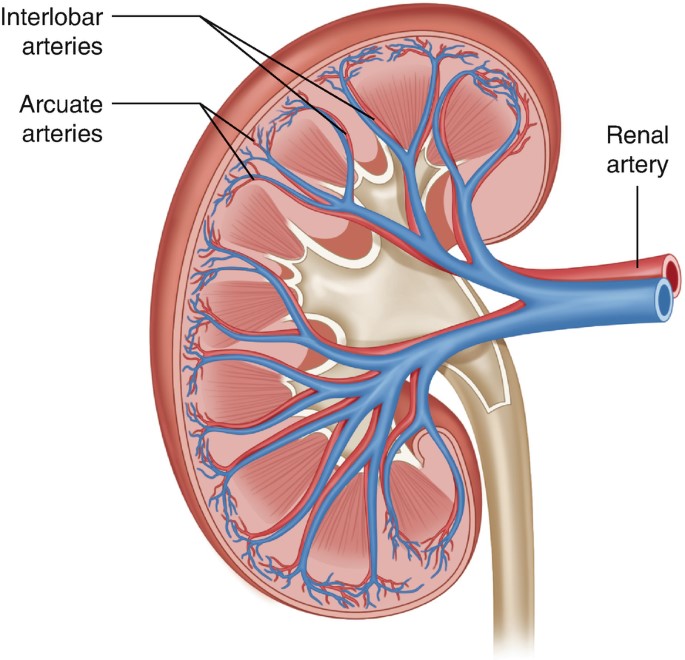

Vascular Structure of the Kidneys

The kidneys are perfused with 1.2 liters of blood per minute, which represents about 25% of the cardiac output (3). From the abdominal aorta, the main renal artery carries blood into the kidney and then branches to segmental arteries, then to interlobar arteries, then branches to arcuate arteries, followed by branching to interlobular arteries, and finally onto afferent arterioles (3). Vascular resistance in the kidney is low when compared to other vascular beds within the body.

Figure 2. Vascular Structure of the Kidneys (3)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you explain the major functions of the kidneys?

- How would you describe the vascular structure of the kidneys?

- Are you familiar with focused physical assessment techniques for assessing peripheral edema?

- Have you ever cared for a patient with impaired renal function?

Pathophysiology of Lupus Nephritis

Have you ever played dominos? If aligned properly, the domino effect will rapidly cause a consecutive reaction. The immune response can be compared to this domino effect. One cellular action will cause the response and activation of many other cells. A perceived foreign body activates certain immune responses. In most cases, this maintains life. In some cases, it is harmful to vital tissue.

An autoimmune response to the renal system involves the T- and B-cell interactions stimulating interstitial plasma cell generation in the kidney; interstitial tissue leads to restricted autoantibody-producing plasma cells (6). This cascade of inflammatory response is facilitated by the production of interferon-α (IFN-α), which augments autoreactive B-cell activation and its reciprocal interaction in T-cell activation. This prolonged local injury and inflammation attracts neutrophils that try to help alleviate this inflammation, but the sustained local injury leads to neutrophil apoptosis (cell death), which further causes local injury. This injury further augments the inflammatory response by enhancing the intrarenal autoimmunity and inflammation, leading to kidney tissue injury (6).

Lupus nephritis is considered a type-3 hypersensitivity reaction. A hypersensitivity reaction is an inappropriate or overreactive immune response to an antigen. Symptoms typically appear when an individual has had a previous exposure to the antigen. Hypersensitivity reactions can be classified into four types (9).

- Type I – IgE mediated immediate reaction

- Type II – Antibody-mediated cytotoxic reaction (IgG or IgM antibodies)

- Type III – Immune complex-mediated reaction

- Type IV – Cell-mediated, delayed hypersensitivity reaction

In type III hypersensitivity reactions, antigen-antibody aggregates called “immune complexes” are formed. When someone has lupus, a number of DNA are damaged and have cell death, which exposes parts of the nucleus in the cell, and parts of the nucleus are recognized by the immune system as “nuclear antigens.” Remember, the immune system attacks antigens. The antigen-antibody complexes are transported by the blood and are deposited in various tissues, such as the kidneys.

When the complexes are deposited, it initiates the recruitment of inflammatory cells (monocytes and neutrophils) that release lysosomal enzymes and free radicals at the site of immune complexes, causing damage to that tissue (9). Examples of tissues that it may deposit in include skin, joints, blood vessels, or glomeruli. In the case of LN, the site of damage is the glomeruli of the kidneys, and it can have a disastrous impact.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you describe the differences between the types of hypersensitivity reactions?

- How would you describe the composition of the antigen-antibody complexes?

- Can you name types of inflammatory cells?

- Can you think of reasons the glomeruli of the kidneys may be a deposit site for free radicals and antigen-antibody complexes?

Clinical Presentation

The clinical manifestations of LN can be unpredictable and very different among patients. Patients may present with no symptoms at all, while other patients may have significant proteinuria progressing to acute renal failure. Understanding the disease and its progress is vital for nurses to provide optimal care and education to the patient. Remember, these patients may have signs and symptoms from their lupus already, so isolating renal impairment is essential.

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of systemic lupus erythematosus depend on the body systems that are affected by the disease. Systemic symptoms include fatigue, malaise, weight loss, anorexia, and fever. The patient may report musculoskeletal symptoms, including joint and muscle pain, joint swelling and tenderness, hand deformities, and skin lesions such as the characteristic “butterfly rash” or maculopapular rash (small, colored area with raised red pimples). Other symptoms stem from the central nervous system (visual problems, memory loss, mild confusion, headache, depression).

It is important for the nurse to establish a history of symptoms related to the hematological system (venous or arterial clotting, bleeding tendencies), cardiopulmonary system (chest pain, shortness of breath, lung congestion), or gastrointestinal system (vomiting, difficulty swallowing, diarrhea, and bloody stools). To differential LN, it is important to focus on specific function impairment and manifestations arising from the kidneys (1).

Nephritic symptoms related to hypertension and poor kidney function:

- Peripheral edema

- Headache and dizziness

- Nausea and vomiting

Nephrotic symptoms related to proteinuria:

- Peripheral or periorbital edema

- Coagulopathy

Patients may report the following:

- Foamy urine

- Blood in the urine

- Dark urine

- Changes in the frequency of urination

- Weight gain and swelling, including the legs and hands

Classifications of Lupus Nephritis

There are six classifications of lupus nephritis:

- Class I: Minimal mesangial

- Prevalence 10-25% of people with lupus (SLE)

- 5% of lupus nephritis cases

- Clinical findings: Kidney biopsy shows build-up of antigen-antibody complex deposits; urinalysis is normal

- Class II: Mesangial proliferative

- Prevalence: 20% of lupus nephritis cases

- Clinical findings: Mesangial hypercellularity of any degree with mesangial immune deposits

- Class III: Focal LN

- Prevalence: 25% of lupus nephritis cases

- Clinical Findings: Active lesions exist in less than half of the glomeruli; hematuria and proteinuria

- Class IV: Diffuse proliferative

- Prevalence: 40% of lupus nephritis cases

- Very severe subtype

- Clinical findings: More than 50% of the glomeruli are affected with active lesions

- Immune complex deposits exist under the endothelial when viewed with an electron microscope

- Hematuria and proteinuria

- Hypertension, elevated serum creatinine, and raises anti-dsDNA (an antibody tested to diagnose lupus)

- Kidney failure is common

- Class V: Membranous

- Prevalence: 10% of lupus nephritis cases

- Clinical findings:

- Hematuria and proteinuria

- Significant systemic edema

- The glomerular capillary wall is thicker in segments

- High risk for renal vein thromboses, pulmonary embolism, or other thrombotic complications; active lesions are present

- Class VI: Advanced sclerotic LN

- Global sclerosis – typically more than 90% of the glomeruli are damaged and have active lesions

- Clinical findings: Progressively worsening kidney function

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some differences in clinical manifestations between renal impairment and renal failure?

- Can you name the different classes of LN?

- How are clinical findings of Class I and Class IV different?

- Can you describe the glomerular function impairment in Class IV LN?

Diagnosis

LN is often the presenting manifestation resulting in the diagnosis of SLE (1). SLE is diagnosed clinically and serologically with the presence of certain autoantibodies. Evaluating kidney function in patients diagnosed with SLE is important as timely detection and management of renal impairment has been shown to greatly improve renal outcomes. The clinical presentation and laboratory findings for LN may differ, ranging from normal urinalysis and normal renal function test results to severe proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, or acute nephritic syndrome, which can result in acute kidney failure (1). Monitoring for the development of lupus nephritis is done by a urinalysis, creatinine, urine albumin-to-creatine ratio, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and a kidney biopsy.

Laboratory tests for SLE disease activity include the following:

- Antibodies to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA)

- Complement (C3, C4, and CH50)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- C-reactive protein (CRP)

Laboratory tests to evaluate kidney function in SLE patients:

- Urinalysis

- Check for protein, red blood cells (RBCs), and cellular casts

- Serum creatinine assessment

- Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) testing

- Spot urine test for creatinine and protein concentration

- 24-hour urine test for creatinine clearance and protein excretion

Urinalysis

A high level of protein or red blood cells in the urine signifies kidney damage. The Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) define renal involvement in lupus as a 24-hour urinary protein excretion of 0.5 g daily or the presence of red blood cell casts in urinary sediment (1). Urinary protein excretion in a 12-hour or 24-hour urine collection provides the best estimate of proteinuria. The most common abnormalities in urinary sediment in patients with LN are leukocyturia, hematuria, and granular casts (1).

Blood Tests

Creatinine is a waste product from the normal breakdown of muscles in your body. Kidneys remove creatinine from the blood. An elevated creatinine reveals damage to the kidneys because it is not functioning as it should. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) also is an important test to determine how well the kidneys are functioning.

Kidney Biopsy

The next step in diagnosing LN would be a kidney biopsy. Kidney biopsy is currently the gold standard for confirming a diagnosis of LN and characterizing the LN subtype on the basis of histological patterns (1). A kidney biopsy is usually performed as a percutaneous needle biopsy with minimization of risk factors for bleeding complications. The piece of tissue removed is examined under a microscope by a pathologist.

A kidney biopsy can (1):

- Confirm a diagnosis of lupus nephritis

- Help in determining how far the disease has progressed

- Guide treatment

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you describe what the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is important for?

- Can you name components of a urinalysis?

- Have you cared for a patient with hematuria?

- Can you think of reasons a patient may be apprehensive about having a kidney biopsy?

Treatment

Treatment of LN is highly individualized. There is not a specific FDA-approved drug specifically given for the treatment of LN. Treatment cannot be a “one-size fits all” approach, but a plan to target renal impairment and avoid causing further damage. The goal of immunosuppressive therapy is the resolution of inflammatory and immunologic activity. Unfortunately, aggressive treatments can result in additional harm to patients. As the therapy of LN consists of potentially toxic drugs, it may be harmful to begin treatment without a definitive diagnosis (4).

Treatment of LN usually involves immunosuppressive therapy and glucocorticoids. The goals of LN treatment are to achieve rapid remission of active disease, prevent renal flares, prevent progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD), minimize treatment-associated toxicity, and preserve fertility (1). Immunosuppressive therapy is used to treat active focal (class III) or diffuse (class IV) LN or lupus membranous nephropathy (class V); but not usually used to treat minimal mesangial (class I), mesangial proliferative (class II), or advanced sclerosing (class VI) LN.

The treatment of focal or diffuse LN has two main components: initial therapy with anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents to slow kidney injury, followed by long-term subsequent immunosuppressive therapy to control the chronic autoimmune processes of SLE and encourage the repair of damaged nephrons (1).

Treatment Goals

- Reduce inflammation in the kidneys

- Decrease immune system activity by blocking immune cells from attacking the kidneys directly and making antibodies that attack the kidneys

- Treatment of systems (hypertension, fluid retention)

- Support kidney function

Medications

Medications for the treatment of LN include (2):

- Corticosteroid

- Prednisone

- Immunosuppressant

- Cyclophosphamide

- Mycophenolate mofetil

- Hydroxychloroquine (Quinoline drug used to treat or prevent malaria; used for autoimmune response)

Blood pressure control:

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs)

- Diuretics

- Beta blockers

- Calcium channel blockers

| Risk Target and Goals | Interventions |

| Lupus nephritis-related mortality | Chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine |

| Control of blood pressure and hyperlipidemia | |

| SLE and LN activity to avoid ESRD | Immunosuppression no less and no more than necessary |

| Hyperfiltration and proteinuria to avoid end-stage renal disease (ESRD) | Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition |

| Avoid drug toxicity | Infections: Reduce or eliminate corticosteroids, PJP prophylaxis, vaccination, personal infection control |

| Malignancy: Avoid cumulative cyclophosphamide of over 30 grams | |

| Fractures: Reduce or eliminate corticosteroids, vitamin D supplementation, bone density monitoring | |

| Symptoms | Improvement or stabilization of the serum |

| Improvement of the urinary sediment | |

| Nephrotic syndrome: loop of Henle diuretics |

Treatment Guidelines

Key points of American College of Rheumatology guidelines for managing lupus nephritis (1):

- Patients with clinical evidence of active and previously untreated lupus nephritis should have a kidney biopsy to classify the disease according to the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) criteria.

- Patients with lupus nephritis should receive background therapy with hydroxychloroquine, unless contraindicated.

- Glucocorticoids plus either cyclophosphamide intravenously or mycophenolate mofetil orally should be administered to patients with class III or IV LN.

- Patients with class I/II nephritis do not require immunosuppressive therapy.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers should be administered if proteinuria reaches or exceeds 0.5 g/day (1).

- Blood pressure should be monitored and maintained at or below 130/80 mm Hg.

- Patients with class V lupus nephritis are generally treated with prednisone for one to three months, followed by tapering for one to two years if a response occurs.

For those who progress to kidney failure, treatment options include dialysis and kidney transplant.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you think of examples of treatments for blood pressure control other than medications?

- Can you think of treatments for LN and the risks of these treatments?

Complications

Complications of LN can be categorized into comorbidities from the actual condition and treatment-associated adverse outcomes. As mentioned, immunosuppressive therapy and glucocorticoids have harmful risks of their own. Comorbidities can include complications of the renal system and cardiovascular system. Treatment-associated complications can include infections, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and reproductive impairment (1).

SLE and treatments, including glucocorticoids and calcineurin inhibitors, can cause hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and nephrotic syndrome (1). Many patients with LN have progressive CKD with associated comorbidities, such as anemia, osteoporosis, and other bone and mineral diseases. These factors contribute to vascular risks of progressive CKD and can lead to cardiovascular disease.

The prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis is high in patients with LN taking immunosuppressive therapy. In patients with severe nephrotic syndrome, a loss of plasma proteins, including clotting inhibitors, transferrin, immunoglobulins, and hormone-carrying proteins (such as vitamin D-binding protein), can lead to protein malnutrition, anemia, hormonal and vitamin deficiencies, hyperlipidemia, and increased risk for venous or arterial thrombosis (1). High-dose cyclophosphamide therapy correlates with premature gonadal failure in some cases, which is a complication of male and female reproductive organs (1).

Immunosuppressive agents increase the risk of infection, which can be further increased by disease activity, leukopenia, and CKD-related factors, such as nephrotic syndrome. Patients receiving immunosuppressive treatment can be at risk for poor outcomes with pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, herpes, hepatitis B, tuberculosis, influenza, and pneumococcal infection (1).

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is a major complication of LN. Some 5–20% of patients with LN develop ESRD (1). By definition, all patients with LN have chronic kidney disease (CKD), but not all patients with CKD progress to ESRD. Essentially, ESRD occurs when the kidneys are no longer able to function to maintain life and either dialysis or a kidney transplant is needed.

Figure 4. Complications of Lupus Nephritis

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you describe how renal impairment impacts the cardiovascular system?

- Can you name signs and symptoms of renal impairment?

- Have you cared for a patient experiencing adverse reactions to medications for immunosuppression?

- Are you familiar with risk factors for long-term corticosteroid use?

Screening and Prevention of Lupus Nephritis

Screening for LN onset and relapses is important for prompt treatment to improve outcomes. There are many new biomarkers under exploration for predicting and assessing LN (1). Patients with SLE should be screened periodically, even during periods of remission, every six to 12 months, or more frequently when clinically indicated (1). During regular check-ups, screening for LN onset or flares in patients with SLE should include evaluation of volume status, blood pressure measurement, urinalysis, and measurement of serum parameters. Elevation of serum creatinine level, the appearance of dysmorphic erythrocytes, cellular casts and new-onset proteinuria may indicate onset of LN (1). Nurses should encourage patients to regularly attend their appointments.

Patient Education

Patient education must be individualized to each unique patient. Lupus or LN may be a new diagnosis, or the patient may have been diagnosed previously. Teaching topics should include education on the disease process, the purpose of treatment regimens, and the importance of compliance.

Education on medication regimens is essential. Include the purpose, dosage, and possible side effects of all medications. Teach the patient when to seek medical attention. Provide tips such as wearing a medical alert bracelet or lanyard noting the condition and medications so appropriate action can be taken in an emergency. Provide resources on smoking cessation for patients who use tobacco. Teach the female patient the importance of planning pregnancies with medical supervision because pregnancy is likely to cause an exacerbation of the disease and the disease may cause negative pregnancy outcomes.

Discuss all precipitating factors that need to be minimized or avoided, including fatigue, vaccination, infections, stress, surgery, certain drugs, and exposure to ultraviolet light. Teach the patient to avoid strenuous exercise, but instead set goals of steady pace and balance. Describe pain management strategies and the importance of adequate nutrition. The patients may have concerns about skin care products and cosmetics. Teach the patient that these products should be hypoallergenic and approved by a provider prior to use. Encourage the patient to contact appropriate support groups available in the area.

Diet

Education on diet and nutrition for patients with LN can be very helpful in managing this condition. A diet regimen can be challenging because many people with this condition may also experience weight loss or gain, inflammation, osteoporosis, high blood pressure, and atherosclerosis. Recognizing specific nutritional concerns for each condition is important. A registered dietitian would be a meaningful resource for those with LN.

A kidney-healthy diet consists of low salt, low fat, and low cholesterol, with an emphasis on fruits and vegetables. Eating the right foods can help patients manage kidney impairment, maintain a healthy weight, and lower their blood pressure. Steroid medications can cause significant fluctuation in weight and energy.

The provider may advise restrictions on dietary protein intake. According to nephrology research, consuming more than 1.5 g of protein per kilogram per day can overwork the kidney filters, causing hyperfiltration (5). Many proteins are composed of amino acids that are converted to acids that are harmful to the kidney in large amounts; a diet high in animal proteins also contains sulfuric and phosphate acids that promote kidney damage (5). Potassium intake is also an important aspect of diet for those with LN. Potassium is secreted by the kidneys and may rise when kidney function declines; abnormal potassium levels can impact muscle function and increase the risk of hypertension, coronary artery disease, or stroke (5). A balanced diet with special considerations is a key teaching factor. It may be helpful to seek out resources from registered dieticians when needed.

Overview of Teaching Topics

Topics for education:

- Disease process

- Treatment plan

- Diagnostic studies and lab results

- Medications

- Purpose

- Dosage

- Side effects

- Contraindications

- Infection control

- Diet

- Tobacco cessation resources

- Reproductive complications

- Techniques to minimize ultraviolet exposure

Resources

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and Lupus Foundation of America (LFA) are excellent resources for patient with lupus that provide education and resources to improve overall well-being. The Lupus Foundation of America has a team of physicians, scientists, health educators, and individuals with lupus who work together to create resources, support groups, awareness initiatives, and programs. Patients can go to the “Ask our Health Educator” portal and get answers to questions they may have.

Conclusion

Nurses need to have a good understanding of lupus nephritis to provide patients with appropriate support and advice about how to maintain wellbeing and lead meaningful active lives. Knowledge on disease pathophysiology, manifestations, treatments, and complications is valuable for this serious condition. Patients often rely on nurses to support and empower them on this pathway.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you describe lupus to a non-medical person?

- Can you describe the difference between normal immune response and autoimmune response?

- Can you name clinical signs and symptoms specific to lupus?

- What is the most reliable diagnostic tool for LN?

- What are some ways the nurse can advocate for a patient having a kidney biopsy?

- How would you empower a patient with a new diagnosis of LN in knowledge of medications and their treatment regimen?

References + Disclaimer

- Anders, H., Ramesh, S., Ming-hui, Z., Ioannis, P., Salmon, J. E., & Mohan, C. (2020). Lupus nephritis (Primer). Nature Reviews: Disease Primers, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0141-9

- Arnaud, Laurent., & Vollenhoven, R. van. (2018). Advanced handbook of systemic lupus erythematosus. Adis. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43035-5

- Hailemariam, F., Falkner, B. (2022). Renal Physiology for Primary Care Clinicians. In: McCauley, J., Hamrahian, S.M., Maarouf, O.H. (eds) Approaches to chronic kidney disease. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83082-3_1

- Jaryal, A., & Vikrant, S. (2017). Current status of lupus nephritis. The Indian journal of medical research, 145(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_163_16

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Mitch, W.E., Fadem, S.Z. (2022). Diet to preserve kidney function. In: Fadem, S.Z. (eds) Staying Healthy with Kidney Disease. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93528-3_7 Maarouf, O.H. (2022). Lupus nephritis. In: McCauley, J., Hamrahian, S.M., Maarouf, O.H. (eds) Approaches to Chronic Kidney Disease . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83082-3_10

- Parodis, I., & Sjöwall, C. (Eds.). (2023). Clinical Features and Long-Term Outcomes of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. MDPI – Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute.

- Pryor, K. P., Barbhaiya, M., Costenbader, K. H., & Feldman, C. H. (2021). Disparities in Lupus and Lupus Nephritis Care and Outcomes Among US Medicaid Beneficiaries. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America, 47(1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdc.2020.09.004

- Usman N, Annamaraju P. (2023). Type III hypersensitivity reaction. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559122/

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click Complete

To receive your certificate