Course

Suicide Risk ER Admission

Course Highlights

- In this Suicide Risk ER Admission course, we will learn about the process for hospital ER admission.

- You’ll also learn to define terms of suicide, suicide attempt, and suicidal ideation, and the prevalence and incidence of suicide in the US.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the treatment and management of a client who is at risk of suicide, including legal and ethical issues related to managing suicidal persons.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 2

Course By:

Tracey Long

PhD, APRN-BC, CCRN, CDCES, CNE, COI

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

This continuing education will help you answer those questions about suicide risk and admission to the ER.

Case Scenario

Chad, a 27-year-old male, is brought into the emergency department (ER) by paramedics after a suicide attempt. His wife found him unconscious in their apartment after overdosing on medication. He is conscious but visibly distressed and angry as he is wheeled into the ER.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- As an emergency department nurse, do you know what to do?

- What labs should be ordered?

- How would you approach your patient and his wife?

- What resources do you have at your work to help him in the short and long term?

- What are the policies and procedures for admitting him?

Suicide in the United States

Having a background knowledge of the risks and statistics of suicide in America is important for ER nurses to have an appreciation of the severity and factors related to suicide.

Prevalence, Incidence, Demographics, and Statistics

One suicide is one too many. Suicide is a tragic event and affects the lives of more than the person who took their own life. It impacts family, friends, associates, and others interacting with the individual. Suicide is beyond a cry for help, as the person believes taking their own life is the only solution to their pain and suffering.

Suicide is the ninth leading cause of death in the United States according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention costing $69 billion and the loss of approximately 48,344 lives in 2022 (1). Suicide rates are estimated to be approximately 14.5 per 100,000 individuals (2). From 1999 to 2016, American suicide rates increased by nearly 30%. Risk factors appear to be multifactorial and not always due to a mental health disorder.

Suicide in the United States has been ranked as one of the highest rates among developed nations and increased by 30% between 2000 and 2020, from 10.4 to 13.5 suicides per 100,000 individuals (3). In the top nine leading causes of death among those ages 10-64, there were almost 46,000 deaths in the United States from suicide in 2020, which is approximately one death every 11 minutes (4).

The rate of those who think about suicide is higher than those who carry it out. In 2020, 12.2 million Americans admitted to seriously thinking about killing themselves, 3.2 million planned a suicide attempt, and 1.2 million attempted a suicide, not resulting in death (5, 75). During the COVID-19 worldwide pandemic, depression rates increased three-fold, leading to an increase in suicide rates in the U.S., especially for men of color (6). Mental health became a publicly discussed health issue more than ever during the pandemic.

According to the CDC, firearms account for 50% of suicides in the United States, followed by suffocation (28%), drug poisoning (11%), and non-drug poisoning (3%) (3).

There has been a steady increase in both completed suicide and suicidal ideation in the past decade, possibly due to the increase in the availability of firearms, but also complicated by the stressful lifestyle of modern society. Interestingly, more suicides occur in rural areas than suburban areas, again possibly due to the availability of firearms (74).

The American Psychiatric Association Assessment and Management of Risk for Suicide Working Group explains the risk of suicide increases with the following conditions (35):

- Psychiatric diagnoses: especially mood disorders, psychotic disorders, anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, and disorders associated with impulsivity.

- Medical conditions: particularly those that are chronic, debilitating, disfiguring, or painful.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is the prevalence of suicide in the United States?

- What is the difference between the incidence and prevalence of suicide?

- What are the most common methods of suicide in the US?

- Why is it important for an ER nurse to know about the risk factors of suicide?

Definition of Terms

Defining terms related to suicide is important to understand what suicide is, versus suicide attempt and the terms related to self-inflicted death.

Suicide is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and accepted as a standard definition as “death caused by injury to oneself with the intent to die” (3).

A suicide attempt is the action of self-harm with the intent to cause death without resultant death.

Suicidal ideation is the continual thinking of self-harm and death but is a broad term describing wishes and preoccupations of death and suicide. Because there is no standard definition for suicidal ideation, it becomes difficult for clinicians, researchers, and educators to identify and even code for it as a diagnosis (7).

Research indicates those with a mental health disorder are at higher risk for both suicidal ideation and eventual suicide, however, one study collected by the Centers for Disease Control revealed that as high as 50% of those who committed suicide had no known mental health disorder (7). Whether those deceased had a mental illness that was not yet diagnosed or not is unknown.

A study in the United Kingdom found that as high as 90% of those who successfully committed suicide had disclosed their suicidal ideation to their primary practitioner and 44% within the month of suicide. This points to the standard policy that a suicide threat should always be taken seriously (8).

The study found that only 22% of those primary care providers believed the threat and suicidal ideation to be a concern as they thought the person would never actually carry out the threat. For all healthcare professionals, this is a huge message and reminder to always take seriously any suicidal ideation of a client.

Imminent harm: An immediate and impending action that will cause bodily harm to self or others is imminent harm. When a client is assessed to be in imminent harm to themself, such as in an emergency department, an emergency legal code may be initiated to legally restrain the person to keep them safe. Each state may have a different code. The factors to consider include the duration of the risk, the nature of the potential injury, and the timeframe before the potential harm would occur.

Lethal: An action that is considered lethal, is sufficient to cause death. When discussing suicide, a legal action would cause the end of life of that person.

Homicide: The deliberate and unlawful killing of another person and is also called murder. Suicide is killing oneself and contrasts with homicide, which is taking the life of another person.

Classifying Levels of Risk

Identifying risk factors for suicide is valuable for suicide prevention. Recognizing which factors lead to suicide helps healthcare professionals classify the level of risk to know which level of action is necessary.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Identify the definition of suicidal ideation.

- Compare and contrast the definition of suicidal attempt and completed suicide.

- What is imminent harm?

- What are methods to determine lethality and suicide risk?

Suicide Risk Factors

Because suicide is multifactorial there are many issues to consider for those that may increase the risk for suicide. There are also protective factors within each category to consider and encourage that may help a person avoid suicidal ideation and behaviors.

Cultural Factors

Culture is defined as the customs, beliefs, behaviors, art, communication style, and dietary habits of a particular group based on ethnicity, race, religion, or even social group (10).

Cultural norms throughout history have had a powerful impact on the individual’s definitions of life, death, wellness, and disease. Historically, in some cultures, self-sacrifice by death could be considered honorable such as the Japanese belief in hari-kari death by disembowelment as a form of seppuku, a ritual suicide.

Suicide by ethnic groups varies with white European Americans having the highest rates, and American Indians and Native Alaskans the highest of ethnic groups (11).

Research also reveals that motivations towards suicide vary among different ethnicities. Latinx or Hispanic individuals were more likely to commit suicide for external stressors such as job loss, divorce, abuse, or discrimination, compared to their white counterparts who cite internal feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness (12). Ethnic minorities often demonstrate more feelings of hopelessness due to discrimination and racism, which puts them at risk for suicidal ideation and suicide (13).

Within culture there is a religious influence among people for their interpretation of the act of suicide. In Christian groups, suicide is considered one of the highest acts against God and is a sin. Other religions may consider suicide as the passing of this one life with a negative consequence for the reincarnation of the next life. Inherent in most cultures however is the sanctity of life and abhorrence of suicide, which in Hindu is termed soul-murder.

Culturally sanctioned doctor-assisted euthanasia is found in some European cultures and is acceptable only for terminal illnesses (13). Interviews with women after a suicide attempt reveal their feelings of not belonging to either culture as their adolescent experience is vastly different from their parents in the country of origin and they feel neither their parents nor peers understood them.

This research revealed that depression may not be the only emotion before a suicide attempt but additionally feelings of anger. Whereas the typical white male will commit suicide with firearms, and have access to them, a younger ethnically diverse population may attempt suicide with hanging or over-the-counter medication overdose demonstrating anger turned within.

Healthcare professionals need to recognize the impact and influence of culture and religion on an individual’s mental health and behaviors, which may either increase or protect against suicidal ideation and behaviors. Application for clinicians is to consider cultural implications along with the generic suicide risk tool that is being used.

Recognizing that Asian and Latinx Americans are generally motivated by external factors and white European Americans may be more motivated by internal factors can help guide the clinician to inquire about life factors that may impact depression, mental health, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

Sometimes the culture itself may create feelings of shame such as the Asian culture of “saving face” versus the shame of letting parents or the general culture down. Some Asian cultures place great emphasis on excelling academically and if a child chooses not to study the topic directed by the parents, or doesn’t have the academic interest or aptitude, the child may experience deep shame and stress (15).

Protective factors within culture for an individual include feeling a sense of community within their culture. Following cultural norms and expectations appears to be protective as those who commit suicide are described as living without the boundaries of the culture such as being isolated and deviant.

Protective factors for any culture appear to be a sense of connectedness and purpose in life. Some people who still experience feelings of worthlessness or hopelessness may still find protection from feeling connected to their culture, family, an individual, or divine responsibility to honor the sanctity of life (13). Teaching traditional values and spirituality within the culture is a protective factor for youth (16).

Geographic Factors

Research shows geographic factors that matter in the incidence and prevalence of suicide.

Those in rural areas, including Veterans, have a higher incidence of suicide, which may be due to the availability of firearms (17). The only exception to that locality factor is African American males who have an increase in suicide in urban areas.

Living in rural areas may also promote social isolation, barriers to access to medical care for counseling and mental health treatment, and dangerous work conditions such as in farming communities. In addition to living in isolated areas, such as rural communities, geographic factors include living in negative and dangerous or disturbing neighborhoods in urban areas.

Protective factors include programs that help recognize people in isolated rural communities. Veteran programs can be helpful to those in rural areas who choose more isolated areas but can still promote a sense of community and belonging.

Telemedicine has been extremely helpful during the COVID-19 pandemic in delivering mental health and general medical care to people in isolation even in urban areas and can be used more in rural settings. The trend of embracing telemedicine during and after the pandemic has helped improve access to healthcare despite poor or no insurance. Sometimes people who have used telemedicine and screened positive for suicide risk are directed to an emergency department, where ER nurses can continue the screening and crisis management.

Economic Factors

External environmental factors such as unemployment and poverty play a role in despair. Areas with people below the poverty line and those who are unemployed do have an increased rate of suicide (18). Eviction and home foreclosure also increase the risk of suicide. Interestingly, a significant worsening of financial status was more significant as a risk towards suicidal ideation than chronic poverty (19).

Poor economic status also contributes to the lack of resources for mental health counseling and medications. The application for healthcare professionals is to assess the individual’s ability to afford psychiatric medications including simple SSRIs.

Protective factors could include robust financial resources, but suicide occurs even among wealthy or economically stable individuals.

Home and Family Factors

Family dynamics and a sense of belonging are key factors that can be either contributors to suicidal risk or protective factors (20). Even when a person may have a sense of family, they may still have a belief that they don’t want to be a burden, which can outweigh the home and family support, as seen in elderly suicide or those with terminal illnesses.

Studies reveal that the perception of a hostile home environment, criticism, invalidation, and lack of support for life choices increases suicidal ideation and behaviors of not just youth but adults (21, 22). Because suicide attempts are 20 times greater than completed suicide, interviews from persons who attempted suicide reveal family disharmony, parental divorce or arguments, sibling conflicts, and lack of support as factors that contributed to their sense of urgency to disappear from life.

Family factors also include a family history of suicide. Physical and genetic predispositions to mental health may be involved, but also important are the pattern of poor stress management and dysfunctional interpersonal dynamics. A history of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, including incest, is a sign of dysfunctional family dynamics. A recent family loss and difficulty grieving can also be a risk factor.

Adverse childhood events (ACEs) accelerate mental health disorders and despair and create negative health outcomes in adulthood (23). The key message for healthcare professionals is to consider family dynamics beyond the individual at risk for suicide. Family intervention and group counseling and support may be needed in addition to the individual attention given for more effective risk management.

Protective factors for home and family include the strength and support a person may feel within a family unit. A sense of validation for their existence by loving family members is powerful. If an individual has mental health disorders or chooses an alternative lifestyle, support and understanding are protective against feelings of isolation and hopelessness.

Mental and Emotional Health

Studies reveal that although mental health disorders are found in approximately 50% of those who commit suicide, it is not a consistent factor for all cases of suicide. The more specific mental health issues include intrapersonal thoughts of a persistent sense of hopelessness, worthlessness, shame, guilt, meaninglessness, and a feeling trapped with no way out (24). Those with a sense of loneliness, separation, isolation, and feeling unloved, or rejected have an increased risk of suicidal ideation and behaviors (24).

In completing suicide screening tools, researchers have noticed that some people will skip the question of previous suicide attempts leading to a false conclusion of lower risk. Significance for clinical personnel is to review the entire instrument for completion before scoring.

Although depression is a recognized precursor to suicide it is not the only factor and is not always present. (23). Screening for depression in all individuals ideally should be done but screening is not adequate if there are no solutions or resources for the person, which could make the depression worse by creating a sense of hopelessness.

It is estimated that up to 18 million adults and 7% of the adult population have depression at any time (25). According to the American Society on Aging, up to two-thirds of elder suicides were related to untreated or undiagnosed depression. Not everyone who has depression should be placed in restraints and confinement for protection. Some screening instruments have fallen out of use after not being able to demonstrate valid and reliable identification of risk factors, such as the SAD screening tool (9).

Protective factors include strong mental and emotional health, but that is difficult for anyone to stay consistent all the time. Life itself is inherently difficult but the concept of resilience is key. Can you bounce back from a bad day within a short period, or do you linger in a state of despair or negative emotions? The ability to be resilient through life’s difficulties is key.

Mental health status and emotional strength can either increase suicide risk or add protection.

Depression

Depression is unfortunately a common emotion and is seen in at least 10% of adults at any time in the United States. Depression is a condition that follows and is interlaced with other health conditions such as the following (36). Depression is the most common mental health disorder as the issues of perceived isolation, hopelessness and lack of purpose are reported for those with suicide attempts and completed suicide.

Conditions that often correlate with depression:

- Cancer: 25% of cancer patients experience depression.

- Stroke: Up to 27% of post-stroke patients (more than 1/4 of all stroke patients) experience depression.

- Heart attack: 1 in 3 attack survivors experience depression.

- HIV: Depression is the second most common mental health condition of those with HIV.

- Parkinson’s Disease: 50% experience depression.

- Eating Disorders: approximately 33-50% of clients with anorexia have a comorbid mood disorder, such as depression (37).

- Substance Use Disorder: Over 20% of Americans with a mood disorder, including anxiety or depression have an alcohol or substance use disorder.

- Diabetes Mellitus: approximately 1/3 of all people with diabetes experience depression (Holt, et al, 2014).

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): 20% of women with PCOS experience depression. (38).

Each of these conditions creates an additional risk of dissatisfaction with life and self-harm. Recognizing the prevalence of depression in the adult population is a call for healthcare professionals to screen all patients with simple questions for suicidal ideation.

Physical Factors

There are interesting theories based on physical factors that may impact the brain’s ability to think clearly and avoid self-harm. One theory proposes that low cortisol levels are seen in people who commit suicide, which may represent a lack of natural fight-or-flight response to stress. Low cortisol levels were found in the family history of suicide or suicide attempt. Lower than normal cortisol levels were also found in those who reported suicidal ideation. (26).

Another physiologic-based theory shows that microglial cells, found in activation of inflammation and stress are found concentrated in the prefrontal cortex of those who committed suicide. Excess microglial cells affect the concentration of neurotoxic waste products compared to neuroprotective metabolites (27).

Glutamine is a dietary amino acid related to mood and sense of well-being and inflammation may also cause alterations that may contribute to a lack of cognitive flexibility, increased impulsivity, poor memory, depressed mood, and suicidality (28).

There is emerging interest in identifying any genetic mutations that may increase the risk of suicidal ideation. Several studies have identified that gene mutations in families of those with increased incidence of depression include variants of the FKBP5 gene (29).

Risks for suicide are multifactorial and the research continues as suicide for any person and family is devastating.

Social Factors

Social isolation, feelings of not being socially accepted, or socially significant such as immigrants or ethnic minorities, are at risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors. The social construct is also related to culture as it involves interpersonal relationships.

Evidence shows that education, social status, and employment play an important role in suicidal ideation and behavior. Social factors include being male, unemployed, a lone person in a household, and divorced, widowed, or separated are strongly associated with death by suicide (30).

Protective social factors involve positive interpersonal relationships. Healthcare primary care providers, such as nurse practitioners, can refer individuals at risk for individual and group counseling and resources to develop improved emotional intelligence and interpersonal skills.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Identify at least 5 risk factors for suicide.

- Compare the statistics of suicide in the U.S. to world incidence and prevalence.

- Compare and contrast the risk factors with protective factors for suicide.

- What would you do if you recognized the behaviors of a colleague that may indicate high suicide risk?

At-Risk Populations

Identifying at-risk populations comes from demographic information about the incidence and prevalence of suicide in the United States. Statistics reveal important information about the increased risk for some individuals, which is worth recognizing. Health departments and national organizations can better create prevention and education programs based on this data.

For example, knowing that Veterans in rural areas are at increased risk of suicide due to isolation and poor access to mental health resources allows Veteran agencies to better accommodate those needs, which has been helpful. As noted in the above-listed risk factors several population groups have been recognized to be at greater risk.

Gender

There is a higher incidence of suicide among males worldwide compared to females. Studies reveal that although the incidence of suicide is low in white males over age 75, those men who do attempt suicide have higher success rates. It is estimated 40 per 100,000 men over age 75 will commit suicide. Gender makes a difference as to the means of committing suicide.

When men attempt suicide, it is with more lethal and violent means such as with guns and ropes. Women over age 75 have much lower rates of 4 per 100,000 and are often less successful with suicide efforts and commonly use less lethal methods such as drug overdose attempts. Women are twice as likely to attempt suicide but when men have greater completion rates than women.

Age

The risk of suicide affects people differently in different age groups. There are two age groups with an increased incidence of suicide which include young adults from 25-34, and again a surge in reported attempts and completed acts in the elderly from age 75-84.

Adolescents with any of the above risk factors of depression, mental health disorders, race, dysfunctional family situation and substance use are at greater risk of suicide.

“During 2019, approximately one in five (18.8%) youths had seriously considered attempting suicide, one in six (15.7%) had made a suicide plan, one in 11 (8.9%) had made an attempt, and one in 40 (2.5%) had made a suicide attempt requiring medical treatment” (31).

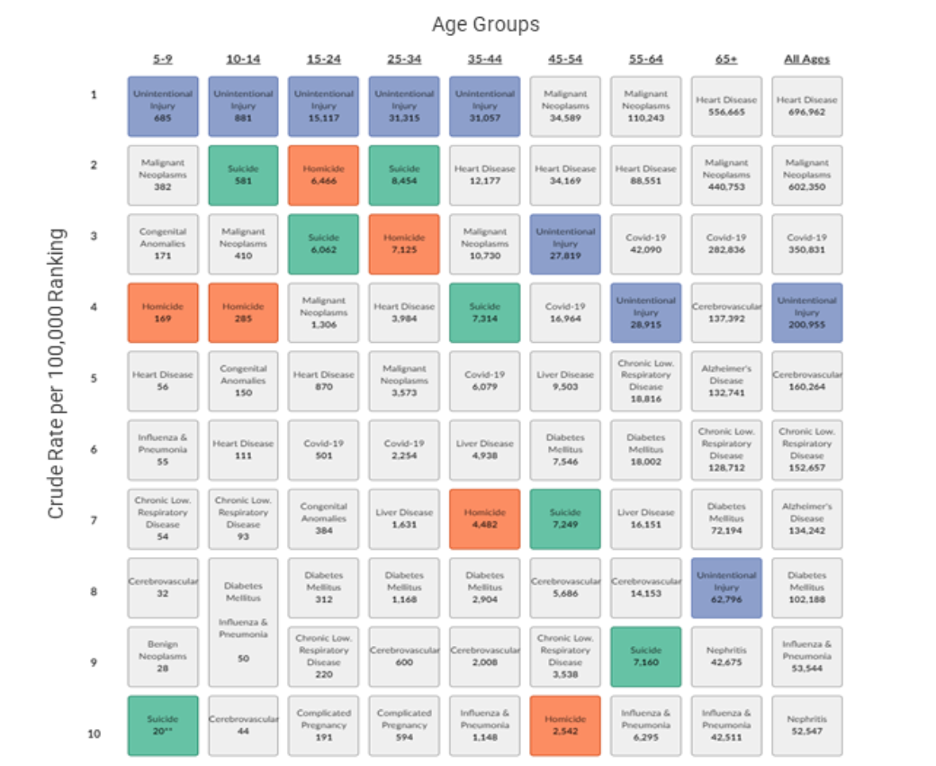

According to the Suicide Prevention Center, suicide was the second leading cause of death for youth ages 10 to 14, and adults ages 25 to 34 in 2020. Suicide was the third leading cause of death for people ages 15 to 24, the fourth leading cause of death for ages 35 to 44, and the seventh leading cause of death for ages 55 to 64 (32).

Image Source: CDC, 2021

Race

Ethnic groups with the highest rates of suicide and suicidal attempts are people of color, non-Hispanic whites, and native American Indians. Race, ethnicity, and culture were discussed earlier.

Diagnosis of Substance Use Disorder

Individuals with substance use disorders (SUD) are at a significantly greater risk of suicide for both males and females than those who don’t partake of addictive substances (72). Most research connecting substance use disorders with suicidal ideation and behaviors was conducted with Veterans, but another study examined the general population and found similar results (72). Using multiple substances is extra risky. Alcohol substance use disorder was the most common substance in the historical use of suicide attempts and completed suicide.

It is acknowledged that SUD and mental health disorders often are seen together. It is understood that the SUD condition is often an effort to deal with difficult mental health issues, family, and social issues and even loneliness and despair. When the combination of SUD and mental health disorders is not treated effectively, individuals often see suicide as a viable way to “make it all go away.”

The key message for healthcare professionals is to increase screening for substance use disorders. Using the Substance Use Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) method of asking simple screening questions should be done at each client interaction.

Military and Veterans

According to the National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report, there are approximately 6000 veteran suicides annually, and 22 veteran suicides each day. The rate of suicides among this unique population is 1.5 times greater than the rate of non-military and veterans (33).

The Veterans Affairs Department (VA) recognizes the incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among veterans who have served in the military and offers free services and education for prevention. Online website training, smartphone apps, and free counseling are available for veterans, healthcare professionals, and families.

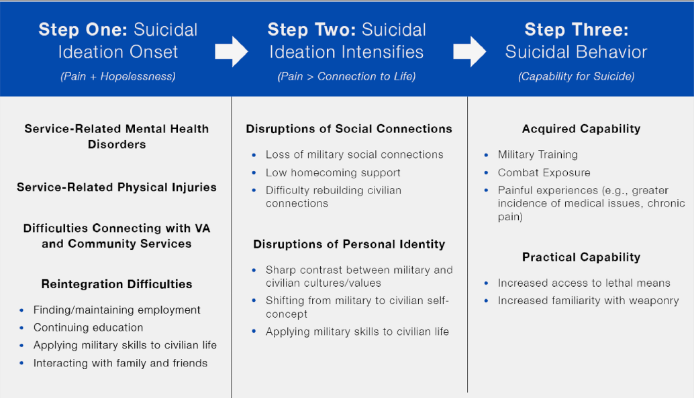

In examining factors that contribute to the increase in suicide among our veterans several contributors have been identified. Transitioning out of the military and into civilian life is the most delicate time as military personnel often struggle to find their new routine and job, culture, new interpersonal relationships, often physical pain from injury, and new purpose (33 The first year of transition has been called “the deadly gap.”

Studies confirm that human beings crave a sense of belonging, which many veterans identify with in their military service. Once they leave that association, they often find a culture gap and few people understand what they may have experienced in war and military service. Veteran suicides represent almost 14% of all suicides even though their population as a group only represents 8% of the adult population (34).

Substance Use Disorder is also a contributor to the veterans’ population which compounds their risk for suicidal ideation and possible suicide (72). Many contributors to this increased risk have been explored such as risk-taking behavior personality that may have drawn them into the military initially, the use of substances to deal with traumatic military experiences, and the skill of firearms. The following diagram depicts these factors for our veterans.

(33)

Our veterans deserve the best medical and psychological care for their service to our country. The role of healthcare professionals, especially primary care providers, is to offer effective screening and education of resources that are available. A challenge is the limited knowledge many medical professionals have about veterans’ resources, which can be difficult to navigate.

Diagnosis of Mental Illness and PTSD

Although it has been assumed all those who commit suicide have a mental health disorder, statistics show only 50% of those who commit suicide had a diagnosed mental health disorder at the time. In contrast, according to the Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults, as high as 90% of people who commit suicide meet the diagnostic criteria for one or more mental health illnesses (35).

Healthcare Providers

A unique population at risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors are the very professionals the general population relies on for healthcare when they are in a suicidal crisis. The emotional and often physical stress of the healthcare job itself can place workers at risk.

Healthcare workers face a unique set of obstacles that increase the risk of suicide. Their demanding nature, long hours, high-stress levels, and exposure to trauma all combine to exacerbate vulnerability, increasing suicide risks. Healthcare providers also endure emotional strain when managing patient suffering and ethical dilemmas while striving to provide optimal care within resource-constrained settings.

As mental illness is still perceived with great stigma in healthcare communities, individuals seeking help for mental health problems might avoid seeking assistance altogether, leading to underreporting and untreated issues of this nature. These factors combine to put healthcare professionals at an increased risk for suicide compared to the general population.

A study in the Journal of American Medical Association revealed physicians to have significantly higher suicide rates compared to general populations, underscoring the critical need for targeted interventions and support systems in healthcare industries to combat this significant threat (77).

Suicide among nurses was publicized more during the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic when nurses and healthcare workers functioned with little sleep between shifts, managed without adequate personal protective equipment, and stood by the bedsides of dying patients on ventilators that couldn’t survive the initial onslaught of the mysterious virus and worked despite fears of exposing their own family and loved ones.

The PTSD they experienced was influenced by feelings of hopelessness when no matter what they did could not stop the fatal power of the virus. Tragically the caregivers in trauma and critical care units often experience PTSD themselves, which we know is a risk factor to suicidal ideation.

Nurses are in a unique position to add mental health screening questions to the intake form of their patients. Likewise, taking time for self-care has become not only acceptable but a popular statement of permission to do what we should have been doing all along: healing the healers.

LGBTQIAS2+ Population

This unique population has been at increased risk for suicide due to the essential elements found in those with suicidal ideation and behaviors such as hopelessness for acceptance, often lack of family support, and lack of customized health resources.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Who are at-risk populations?

- What are the conditions that create the increased risk for people who identify as LGBTQIAS2+?

Special Populations at Risk

Youth and Suicide

Suicide in youth most occurs between the ages 13-21 (69). Suicide by gender also reveals that teen girls from 12-19 are the highest incidence. Thankfully, suicide under the age of 5 is difficult to find in research and statistics. Risk factors include the lack of support and resources, or perceived by the teen, to help them address life’s challenges of critical decisions, high expectations at home, school, athletics, or anything of a competitive nature.

Mental health disorders are found in 90% of teen suicides. The most common disorder is depression. Other common disorders include anxiety and eating disorders that create distress for the individual. About 33% of suicides were proceeded by a suicide attempt or call for help.

As high as 50% of teens who committed suicide had a family member with a mental health disorder. It is supposed that the youth was modeling the maladaptive behaviors seen in the home. Divorce, violence in the home, and negative interpersonal relationships outside the home, such as a romantic breakup, have a great impact on young minds and can become fatal when they are not taught problem-solving skills.

Veterans and Military Personnel

A unique population at risk are our veterans and military personnel due to the added violence they have been exposed to and access to lethal means. Screening should be done by primary care providers, but that means the provider must be aware of their military history and service. Veterans Affairs has created extra programs after recognizing their unique added risk.

Suicide and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Not only did the coronavirus, known as Covid-19, cause the death of millions worldwide, but it created a never-before seen burden on healthcare workers who were exposed to the virus themselves, as they cared for dying patients. The rates of mental health distress, depression and anxiety soared among healthcare workers, which led some to suicide in an often-hopeless environment without adequate personal protective equipment and effective therapies.

It is estimated that in 2020 Covid-19 affected 213, 237, 126 individuals worldwide pending adequate reporting, and result in 4,452,903 deaths including some healthcare professionals.

(70). Those numbers continue to change and still increase each month.

As the burden of new mutations of Covid, including the BA.5 subvariant, take their toll on our vulnerable populations, the nursing shortage has worsened across America. A projected shortfall of 44,500 nurses is estimated by 2030 based on the current workforce and estimated need in hospitals. In the past two years exhausted nurses have left the bedside leaving gaps in direct patient care and facility administrators scrambling for compassionate and competent healthcare workers. Even nurses loyal to the profession have changed their bedside role.

A silver lining through the Covid-19 pandemic has been the new awareness of mental health challenges and stress among healthcare workers. Because of devasting suicides among “our own” more attention to the emotional resilience and well-being of our workers began. Hospitals and administrators began offering counseling, services, and screening.

Much is still needed but at least we as professionals have begun to recognize the healing of our professionals. Just as nurses are taught the risk factors and signs for suicide risk in the general population, we are now being taught to recognize those same signs in our colleagues including irritability, depression, truancy on shifts, appearance of disinterest and just going through the motions at work. Healthcare workers are also at greater risk for substance use disorders due to the increased stress of work and accessibility to medications and mind-altering substances.

Elderly and Suicide

Worldwide suicide rates show that increasing in age increases the risk of suicide, especially of those with chronic disease, or living alone. In the United States, assisted suicide is not a legal option, yet those who experience loneliness after a spouse dies, or have no family members to rely on are at increased risk for self-harm to end it all.

Primary care providers can follow up with care screening questions to identify risk factors. The challenge is always having the time in the insurance reimbursement squeeze of time. Offering seniors access to community services to prevent loneliness such as interest groups or those offered through accountable care organizations in your community can be helpful. Case managers have a unique role as well in being able to make routine phone calls to assess for risk and provide resources.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What screening tools are available for these populations of risk?

- What is a strategy to help family and friends recognize the risk for suicide among their loved ones?

- Why are healthcare professionals, including nurses, at risk of suicide?

- What are you doing now to prevent suicidal thoughts yourself?

ER Suicide Screening and Assessment

Generally, the first medical professional in the hospital the individual will encounter after a suicide attempt is an ER nurse. The ER nurse is in a unique position to approach the person with compassionate and competent care.

Nurses deliver unconditional care and compassion for patients who are hurting both physically and emotionally. It is often the nurse who serves as the advocate for the patient by providing resources and communication with the family. A careful screening and assessment of all patients for suicide risk is important, especially in the ER as ER nurses encounter a large cross-section of individuals needing immediate help.

The Interview Process and Asking about Safety

Nurses, nurse practitioners, and healthcare workers can improve the ability to identify those at risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors with appropriate and effective screening questions. Often when a provider is unsure about a suspicion for the client’s risk of suicide, completing an objective screening tool can help clarify the risk factors and client’s mental state.

Just by taking this continuing education course, the topic of suicide and recognition of those at increased risk hopefully becomes forefront in your mind. A screening tool beyond a checklist is more valuable and allowing privacy for a client to complete the assessment is also valuable to get genuine responses. This assessment can be completed ideally in an emergency department by the nursing staff.

Screening Tools

The Joint Commission's NPSG 15.01.01 now requires healthcare professionals to use a validated tool to assess suicidal risk for all patients with reasons for seeking healthcare is the treatment or evaluation of a behavioral health condition (40).

When using a suicide risk tool in an emergency department, those patients who were ambivalent about living had a double increased risk of suicide and those with active suicidal ideation who had active thoughts and plans of suicide had a three-fold increase in probability of suicide within 30 days (41, 73).

Various screening tools and instruments exist and may be used differently in a primary care office setting versus an emergency department.

The most common screening tools used in office settings are:

- P4 Screener: a 4-question screening tool that asks the “4 P’s” of past suicide attempts, a plan, probability of suicide, and preventive factors (42).

- PHQ-2 Patient Health Questionnaire 2: this is a simplified 2-question screening for those at risk for harm to themselves or others. (43).

- PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire 2: this is the 9-question version of the PHQ-2.

- Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS): questionnaire to assess suicidal behavior and reveal suicidal ideation for pediatrics to adults (44).

The most common suicide risk screening tools used in emergency departments with strong validity and reliability include:

- Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ): a 4-question screening tool for pediatric & young adults who present with medical complaints. It is recommended to administer without the parent/guardian being present.

- Manchester Self-Harm Rule (MSHR): uses 4 questions to identify the ED patient's risk of suicide or repeating self-harm based on their history.

- Risk of Suicide Questionnaire (RSQ): a 4-question screening tool suitable for 8 years through adult; it takes 90 seconds to complete.

The Joint Commission has approved these additional screening instruments as valid and reliable:

- Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS): a 20-item questionnaire measuring pessimism and hopelessness (7).

- Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSI): a 21-item self-report instrument for detecting and measuring the current intensity of the patients’ specific attitudes, behaviors, and plans to commit suicide during the past week. The first 5 questions can be used as a screening tool (50).

- Scale for Suicide Ideation-Worst (SSI-W): a 19-item rating scale that measures the intensity of patients’ specific attitudes, behaviors, and plans to commit suicide at the period when they were the most suicidal. It takes 10 minutes to complete (7).

- Death/Suicide Implicit Association Test (IAT): developed by Harvard to test implicit thoughts towards death and suicide.

- Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale (GSIS): a 30-item questionnaire assessing suicidal ideation on a Likert scale and customized for ages 65+ (45).

- Nurses Global Assessment of Suicide Risk (NGASR): useful for new nurses in completing a clinical assessment.

- Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI): a classic 19-item questionnaire for clinicians or self-ratings (paper or computer-based).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Name at least 3 screening tools that can be used in the emergency department.

- How would you describe the SBIRT tool to other colleagues you work with?

Recognition of Warning Signs

Unfortunately, despite decades of research to identify possible risk factors of suicide, there is no one clear profile person or set of behaviors that reliably identify a suicidal personality. The conclusion from numerous studies is that suicidal thoughts and behaviors are due to a complex interaction of psychological, biological, environmental, interpersonal, and cultural factors. (46)

Unlike physical conditions that be assessed and identified visibly or with diagnostic instruments, the emotional components of suicidal ideation are complex and there is no one single screening instrument that is always reliable. What research does conclude is that by using any screening tool, and with the genuine sincerity of the practitioner, someone at risk may feel safe enough to open up.

The approachability and authentic compassion of the provider is a key factor in a client honestly expressing suicidal thoughts. Unfortunately, many healthcare providers are working with tight time constraints and limited client interaction, especially in urgent care settings. Practitioners working in a primary care office setting may also not even consider a client is at risk for suicide when the primary chief complaint is something common or mundane.

In one study, five categories of identifying factors should be assessed to identify those at risk for suicidal ideation or behaviors.

Effective suicide screening instruments should assess these components (47).

- Internal psychopathology (e.g., anxiety disorders; mood disorders; hopelessness; emotion dysregulation; sleep disturbances)

- Demographic factors (e.g., age; education; employment; ethnicity; gender; marital status; religion; socioeconomic status)

- Prior suicidal thoughts and behaviors (e.g., prior deliberate self-harm, non-suicidal self-injury, suicide attempt, suicide ideation)

- External psychopathology (e.g., aggressive behaviors; impulsivity; incarceration history; antisocial behaviors; substance abuse)

- Social factors (e.g., abuse history; family problems; isolation; peer problems; stressful life events)

Studies have identified common thought patterns of those who begin to entertain suicidal thoughts as when people perceive themselves to be a burden and don’t have a sense of belonging. These negative thought patterns begin to overcome the instinct of fear of death (48). When a person’s negative thought processes dwell on non-existence, it is said they develop the capability to die.

Repeated exposure to negative events and thoughts perpetuates the feelings of being burdensome and not belonging. If emotional pain is greater than connectedness and purpose the risk of suicide becomes greater.

The feeling of hopelessness was key, and an important concept for healthcare professionals to assess. Using standardized tools to assess for the lack of purpose, belonging, and hope are the critical concepts to assess and screen for.

The concern is that there is no one perfect screening tool, and results vary based on the provider’s personal prejudices, time constraints by the provider and the medical team to assess and address risk factors, cultural considerations of the client, cognition of the client, and current management of mental health disorders (49).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are the warning signs of suicidal ideation?

- What should effective suicidal screening tests inquire about?

- What is the Nurse Practitioner’s responsibility for a suicidal client?

Assessing Lethality

After recognizing risk factors and warning signs, a nurse should assess the lethality and possibility of fatal actions by the client. Some warning signs may actually be indicative of depression and not a true risk for self-harm, however other behaviors may be indicative of a fatal act.

Death or survival depends on various risk factors that affect the degree of lethality. When completing a lethality assessment, three parts should be considered including 1) the degree of planning for suicide, 2) the potential of perceived lethality by the person, and 3) the accessibility to the means to carry out the desired action (51).

A suicide inquiry examines the ideation, plan, behavior, and intent of the client. Assessment tools ideally should be culturally appropriate and continue to be developed yet take time. Although many people have suicidal thoughts, not all will move forward to lethal actions.

It is important to recognize that suicidal thoughts can also move across a spectrum so the client with same risk factors may be at higher risk pending environmental and mental health triggers. Recognizing which risk factors can be modified is also important for a provider when making interventions and recommendations.

Identifying protective factors have not been as researched as risk factors but according to the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention has identified the following such as effective clinical care, access to healthcare and interventions, support from medical professionals and family members, problem solving skills, and cultural and religious beliefs that discourage suicide (52).

Levels of Risk

Completing the screening survey is just one step, however, the practitioner needs to identify the score and level of risk. Just documenting the risk assessment score is not adequate. A meta-analysis study revealed that despite recognizing of warning signs and clear risk factors on an assessment, 95% of those did not commit suicide however 50% of those who did were in the low-risk categories (53). Perhaps less important than a score is to truly assess the client’s physical behaviors and emotional affect, and then take appropriate actions.

It is important to distinguish between active and passive suicidal ideation. Active suicidal ideation is when a person has a conscious desire for self-harm and death as a result. The means of inflicting death should not be the key focus, but rather the thought process and person’s expectation that their attempt could be fatal is the primary concern (54).

An example of an active suicidal ideation assessment item is the Modified Suicidal Ideation Scale (Miller et al, 1991) which asks questions such as:

- "Over the past day or two, when you have thought about suicide, did you want to kill yourself? How often? A little? Quite often? A lot? Do you want to kill yourself now?"

Examples of passive suicidal ideation assessment items include:

Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI) with questions to measure "passive suicidal desire.”

- 0 = Would take measures to save [one's own] life

- 1 = Would leave life/death to chance

- 2 = Would avoid steps necessary to save or maintain life

European Depression Scale (55) that asks:

- "In the past month, have you ever wished you were dead?"

Documenting Suicide Risk

Documenting suicide risk must be done as always after a provider’s visit, as in any documentation of a visit. The name of the risk screening tool and score should be included in the notes, along with interventions for safety and client/family education.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are methods to determine lethality and suicide risk?

- How should suicide risk be documented in your department?

- Explain the levels of risk scale for suicide.

Healthcare Provider Training

Due to the continual high rates of suicide and suicide attempts, more effective suicide prevention strategies are needed. Ideally, if we knew exactly how to prevent suicide, there would be no more suicides, however the reality is much more complicated. Several ideas have been proposed including better training for practitioners to screen and interview effectively, and to reduce access to firearms (56).

The Joint Commission has issued recommendations for healthcare professionals and primary care providers to do the following before a client leaves an appointment or the ER:

- Review each patient’s personal and family medical history for suicide risk factors.

- Screen all patients for suicide ideation using a brief, standardized, evidence-based screening tool.

- Review screening questionnaires before the patient leaves the appointment or is discharged.

- Act based on the assessment results to inform the level of interventions needed (40).

Teaching family members and friends to support someone in a suicide crisis requires clear guidance (75).

Healthcare professionals can begin the public awareness of how to help such as the following actions:

- Talk openly and honestly. Don’t be afraid to ask questions like: “Do you have a plan for how you would kill yourself?”

- Remove means such as guns, knives, or stockpiled pills.

- Calmly ask simple and direct questions, like “Can I help you call your psychiatrist or counselor?”

- If there are multiple people around, have one person speak at a time.

- Express support and concern

- Don’t argue, threaten, or raise your voice.

- Don’t debate whether suicide is right or wrong.

- Try to model calmness in your own body.

- Be patient with the person.

- Use the phrase “It’s safe for you to share your feelings with me because I care about you.”

- Let the person know there are healthcare professionals who can help them with their thoughts.

Recognition of Warning Signs

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, recognizing warning signs and behaviors of someone about to commit suicide include the following:

- Increased alcohol and drug use

- Aggressive behavior

- Withdrawal from friends, family, and community

- Dramatic mood swings

- Impulsive or reckless behavior

- Collecting and saving pills or buying a weapon

- Giving away possessions

- Tying up loose ends, like organizing personal papers or paying off debts

- Saying goodbye to friends and family

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is a strategy to help family and friends recognize the risk of suicide among their loved ones?

- How can you support the family of an individual who has attempted to commit suicide?

- What phrases should you never use to an individual who has attempted suicide?

Treatment and Management of Clients at Risk

Treatment and management of clients at risk for suicide is based on the unique risk factors and needs of the individual client. Several strategies including different therapies have been studied and are available.

Medical Management of Mental Illness

According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) as high as 46% of those who committed suicide had a mental illness (2). Management of clients with mental illness is one important treatment strategy. When clients with mental illness are not treated appropriately with effective pharmacological management or counseling, the risk of suicidal ideation increases.

The concerning mental health issues include intrapersonal thoughts of a persistent sense of hopelessness, worthlessness, shame, guilt, meaninglessness, and a feeling trapped with no way out (12). A combination of depression, anxiety, or psychological disorders can compound the feelings of hopelessness. Research shows that both pharmacological treatment and cognitive behavior therapy for mood disorders including depression and bipolar disorder, which are among the most common disorders in the world, have better outcomes than either strategy alone (61).

Currently, antidepressant medications used for mood disorders include monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants. In the past two decades, the more commonly prescribed agents that block the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin/noradrenaline-reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (62).

Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) has been the most researched therapy for the treatment of mood disorders and shows statistically significant improvements in mood for participants. ER nurses can also help patients obtain access to mental health services in their community. Knowing and sharing which mental health services are available is a way of advocating for patients experiencing depression and stress.

Management of Substance Abuse

As substance use disorder is associated with an increase in suicide risk, the ER nurse should screen for substance use. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is an evidence-based practice used to identify, reduce, and prevent problematic use, abuse, and dependence on alcohol and illicit drugs (5). The SBIRT model is the practice of having healthcare professionals, from physicians, nurses, nursing assistants, medical assistants and any medical person who interacts with patients, screen for substance use and abuse. If the patient’ screen is positive, the healthcare professional refers them to available programs and community resources. SBIRT is an early and brief intervention of screening questions and takes less than 5 minutes. An additional history, physical exam, and clinical diagnosis of substance abuse disorder take an additional 10-20 minutes. The time for asking screening questions and offering resources is billable to Medicare/Medicaid. The screening and referral to treatment includes a patient encounter, history, physical exam, clinical diagnosis, and plan for care specific to the concern of substance abuse.

A key aspect of SBIRT is the integration and coordination of screening, early intervention, and treatment components into a system of care. The link between substance uses and suicidal ideation has been documented (5).

It is estimated that a person with a substance abuse addiction must be asked at least 10 times by a healthcare professional before they even move towards contemplation in the behavior change process. You may be person #2 or #10 but it takes screening without judgment, in the spirit of help and coaching to move a person forward to begin to consider substance use. Many people in a substance abuse pattern want to stop but don’t know how or what their resources are.

Simple questions to begin with include “Do you smoke?” If yes, then ask about the frequency of daily consumption and years smoked to calculate pack years. The next important question is simply to ask if they have a desire to stop smoking. If the answer is yes, then you can offer programs and resources. If the answer is no, then let them know you are concerned about their health and you are available with resources when they’re ready to stop.

Each time you have a patient encounter, simply go through the same questions and eventually the person may begin to be in the contemplative stage of change. For alcohol and illicit drug use using the CAGE format is an acronym to help you remember to ask certain questions.

Many people with a substance use disorder may feel like they are in a CAGE and just need help to get out.

C: Have you ever felt you needed to Cut down on your drinking? ...

A: Have people Annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? ...

G: Have you ever felt Guilty about drinking? ...

E: Have you ever felt you needed a drink first thing in the morning (Eye-opener) to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover?

Learning how to become comfortable with asking the screening questions takes practice and you can overcome any hesitation you may feel that you are prying into their personal life by practicing simple questions. Asking the screening questions is a strong start and then referring clients to effective resources for cessation and recovery is the next important component of SBIRT.

You need to learn what resources are available in your community such as free Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and groups, and more. A simple Google search is a good place to start. There are also many free national resources such as the 1-800-quit-now phone lines that will offer resources to individuals seeking help.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What screening tools do you currently use in your ER for suicidal ideation?

- What screening tools do you want to learn more about?

- After the acute stage of a suicide attempt, what are the treatment strategies for a patient?

- What is the role of the nurse in helping with the transition from the acute crisis stage to admission?

Suicidal ER Admission

ER nurses play a strong role in caring for a patient being admitted after a suicide attempt, one who verbalizes a high threat of suicide, and those who screen at risk for suicide.

When patients who have attempted suicide arrive at an ER for evaluation and admission, several critical steps must be followed to ensure their safety and provide appropriate care. Initial assessment takes place in the triage area where a nurse assesses and prioritizes care based on the severity of injuries sustained and mental health status.

Nurses working in triage play an invaluable role in quickly recognizing patients in need of immediate medical assistance, particularly those at risk of further harm or worsening health conditions.

After receiving reports from paramedics regarding any attempted suicide attempts and methods used in attempts, as well as interventions taken en route to hospital care, the nurse gathers pertinent details to share with the provider.

This report aids emergency room physicians and clinicians with their evaluation and treatment plan. Following triage and initial assessment, the nurse conducts a full physical exam on the patient to assess physical health issues because of attempted suicide as well as any injuries from the attempt (78).

This assessment includes vital signs monitoring, wound examination, and neurological testing to detect trauma or intoxication symptoms. Nurses conduct mental health evaluations to detect any psychiatric conditions or risks and assess an attempter's suicide risk.

Safety must always come first when caring for such individuals. Nurses work closely with hospital security to create an atmosphere conducive to patient safety and staff wellbeing. Security measures implemented may include continuous observation of patients and removal of potentially hazardous objects from the area near them; in addition to maintaining a calm, supportive atmosphere in the emergency department (ER).

Working closely together between nurses and security staff is vital to effectively address safety concerns and avoid additional injury. Security staff may assist in de-escalating volatile situations and assuring physical safety for both patients and others in the emergency setting.

Together with nurses and security personnel, nurses and security personnel can manage admission processes for those who have attempted suicide efficiently and compassionately while offering comprehensive emergency care in this setting.

Labs and Diagnostic Tests

Healthcare providers assessing suicidal patients in medical settings typically order laboratory and diagnostic examinations to evaluate physical health issues, identify any underlying medical conditions, and assess any self-inflicted injuries sustained during evaluation. These tests may differ based on an individual patient's presentation, medical history, and clinical judgment.

Some common lab and diagnostic tests that might be done for someone post-suicide attempt or in an acute suicide crisis include (80):

- Full Blood Count (CBC): This provides detailed information regarding red and white blood cell counts, platelet count, and hemoglobin levels of an individual patient. Abnormalities in these parameters could indicate serious medical conditions like infection, anemia, and other blood disorders.

- A Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP) measures various organ function markers including electrolyte levels, kidney, and liver enzyme levels such as creatinine urea nitrogen ratios as well as liver enzyme activity including Alanine Amitransferase, Aspartate Amitransferase levels as well as glucose concentration levels.

- Urinalysis: Urinalysis evaluates both physical and chemical characteristics of urine samples to detect metabolic imbalances or organ dysfunction, including any trace amounts of blood, proteins, glucose, or abnormal cells present. Urinary tract infections, kidney dysfunction, or metabolic disorders may all be detected using simple labs and then a simple ultrasound.

- Drug Screening: Toxicology screening may also be conducted if substance abuse or overdose is suspected. This process typically includes clinical interviews, standardized assessment tools, and collaboration between mental health providers.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What lab tests may be taken on someone who has attempted suicide and why are they done?

- What is the relationship between suicidal ideations and possible physical disorders?

Legal and Ethical Issues with Suicide

Even with the best intentions to help people at risk for suicide, there are legal and ethical issues to consider. Privacy and the right to choose are still key concepts in our society. ER nurses are the frontrunners in seeing the legal side of protecting patients often against their will. When a patient is brought into the ER after a suicide attempt or threat of suicide, the admitting provider may write an order for a 72-hour emergency hold. This is about the legal statute that a person may be held against their will if they are deemed a threat to themselves or others.

Ideally ER admission for suicide should include a safe and compassionate environment, however, most emergency departments (EDs) lack the facilities, staff or expertise required to respond appropriately when dealing with mental health emergencies. Furthermore, most EDs tend to be noisy and disorganized environments unsuitable for de-escalating behavioral health crises. Retrofitting emergency departments to handle behavioral health and suicidal patients is expensive for many hospitals.

Even with adequate funding in place, psychiatric patients frequently experience more stigma and bias when receiving emergency care, including being made to undress without privacy as they may be placed in a hallway for easier monitoring, prolonged boarding times, and minimal therapeutic support during that period (79). ED patients generally don't benefit from much therapeutic assistance during that time. Basic needs like showering, brushing teeth, using the phone, and eating can be extremely challenging for psychiatric patients in ER settings.

An emergency department mental health evaluation does not aim to initiate or provide even short-term mental healthcare but to assess an individual's risk of self-harm (80). Such assessments only consider admission or discharge requirements without providing recommendations for actual treatments or recommendations to manage conditions that have arisen during evaluations.

As part of an overall suicide risk screening in an emergency department (ED), brief screening for suicide risk has limited sensitivity in identifying which patients pose the highest risk. However, low-risk patients can still be identified, and those in which psychiatric holds and real-time psychiatric consultation while in the ED may no longer be necessary allowing more expeditious discharge from the ED.

The role of the ER nurse in admitting a suicidal patient is a careful and delicate one due to the potentially lethal outcomes if a patient is discharged unsafely. Suicidal patients may be admitted into a psychiatric unit where security is provided at a higher level and psychiatric consultations are given. Ideally, the patient will be able to receive further assessments and referrals for appropriate services. Unfortunately, an ER nurse may never know the outcome of their careful attention to the suicidal patient, but knowing the nurse did all possible within their scope can still help. ER nurses can make a difference by becoming more active in public legislation for safe facilities for mental health patients, improvements in hospital policy development and staffing, and effective use of existing screening tools.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are ethical issues to consider for an ER nurse about admitting a patient without adequate safety measures?

- What is the role of the nurse in the transition process from the ER to admission?

Case Study Continues

Due to careful and compassionate care from an emergency room nurse, Chad, the 27-year-old male who was brought into the ER after a suicide attempt was admitted and provided with appropriate psychological evaluation and referral for counseling services. After arriving at the emergency department following an attempted suicide attempt, he was met with kindness from a dedicated nurse.

Recognizing how urgent his condition was, she swiftly coordinated his admission process, so he received immediate medical care. With compassion and professionalism, the nurse conducted a detailed assessment, covering both physical and mental aspects of her patient's illness. Once stable, he continued receiving support from the nurse as his condition stabilized over time.

Recognizing the necessity for psychological evaluation and counseling services, the nurse collaborated closely with the healthcare team to facilitate the transition of the patient to appropriate mental health resources. The nurse advocated on behalf of his patient's needs, making certain he received follow-up care and support to address mental health concerns and reduce future self-harm risk. Through careful intervention and a compassionate approach by this ER nurse, the patient felt heard, understood, and supported during a vulnerable moment in his life.

With access to comprehensive mental health services as well as ongoing support services available at his disposal, his journey toward recovery was enabled thanks to a compassionate ER nurse who made such a significant difference when needed the most.

Resources

* Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline1-800-273-TALK (8255). Here is a list of international suicide hotlines.

* Text TALK to 741741 for 24/7, anonymous, free counseling.

* Call the SAMHSA Treatment Referral Hotline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357), for free, confidential support for substance abuse treatment.

* Call the RAINN National Sexual Assault Hotline, 1-800-656-HOPE (4673), for confidential crisis support.

* Call Trevor Lifeline, 1-866-488-7386, a free and confidential suicide hotline for LGBT youth.

* 7 Cups and IMAlive are free, anonymous online text chat services with trained listeners, online therapists, and counselors.

Veterans Crisis Line 1-800-273-8255 or text 838255 or go to veterancrisisline.net

Conclusion

Suicide remains one of the leading causes of death in the United States. Risk factors have been identified and solutions proposed. Various prevention strategies include mental health awareness, public awareness for suicide prevention and detection, addressing limited access to lethal weapons, addressing unique concerns for high-risk sub-groups such as offering school-based resources for youth, educating healthcare primary care providers as the gatekeepers, staffing crisis hotlines, and promoting more free counseling services with legislation and tax funds.

Suicide is a complex issue and there are no single solutions. It will continue to require a multifactorial approach that addresses the cultural, economic, political, social, and religious factors. Every effort as a Nurse Practitioner to truly connect with your patients, provide screening, and offer real resources, is a life that may be saved.

References + Disclaimer

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2022a). Suicide data and Statistics. NCHS Data Brief. Number 433, March 2022. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/suicide-data-statistics.html

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): https://www.nimh.nih.gov

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022b). Facts about Suicide. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html#:~:text=Suicide%20is%20death%20caused%20by,suicide%20or%20protect%20against%20it.

- National Vital Statistics System. NVSS Vital Statistics Rapid Release: Provisional Numbers and Rates of Suicide by Month and Demographic Characteristics: United States, 2020.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA (2021). Key substance uses and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/suicidal-thoughts-and-behavior-33-metropolitan-statistical-areas-update-2013-2015

- Nevada Coalition for the Prevention of Suicide (2020). Suicide Facts and Figures. Retrieved from https://nvsuicideprevention.org/facts-about-suicide/

- Harmer B, Lee S, Duong TVH, Saadabadi A. Suicidal Ideation. 2022 May 18. In: StatPearls Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 33351435.

- Stene-Larsen K, Reneflot A. Contact with primary and mental health care prior to suicide: A systematic review of the literature from 2000 to 2017. Scand J Public Health. 2019 Feb;47(1):9-17.

- Warden S, Spiwak R, Sareen J, Bolton JM. The SAD PERSONS scale for suicide risk assessment: a systematic review. Arch Suicide Res. 2014;18(4):313-26.

- Merriam-Webster dictionary. nd. Culture defined. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/culture

- Clay, R. (2018). The cultural distinctions in whether, when, and how people engage in suicidal behavior. American Psychology Today. Vol 49, No. 6, p. 28. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2018/06/ce-corner#:~:text=While%20Asian%2D%20and%20Pacific%20Islander,groups%20as%20well%2C%20Odafe%20adds.

- Chu, J., Khoury, O., Johnson, M. Bahn, F., Bongar, B., and Goldblum, P. (2017). An Empirical Model and Ethnic Differences in Cultural Meanings Via Motives for Suicide. Journal of Clinical Psychology. Vol 73, Issue 10, pp. 1343-1359. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jclp.22425

- Pierre JM. Culturally sanctioned suicide: Euthanasia, seppuku, and terrorist martyrdom. World J Psychiatry. 2015 Mar 22;5(1):4-14. doi: 10.5498/wjp. v5. i1.4. PMID: 25815251; PMCID: PMC4369548.

- Simes, D., Ian Shochet, Kate Murray, Isobel G. Sands. (2022) A Systematic Review of Qualitative Research of the Experiences of Young People and their Caregivers Affected by Suicidality and Self-harm: Implications for Family-Based Treatment. Adolescent Research Review 7:2, pages 211-233. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/citedby/10.1080/13811118.2017.1304305?scroll=top&needAccess=true

- Tran, K., Joel, Y., Wong, K., Oakley, O., Brownson, C., Drum, D., Awad, G., and Wang, M. (2015) Suicidal Asian American College Students’ Perceptions of Protective Factors: A Qualitative Study, Death Studies, 39:8, 500-507. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07481187.2014.970299

- LaFromboise, T., Malik, D., Saima, S. Zane, N., Guillermo, B., Leong, F. (2016). Evidence-based psychological practice with ethnic minorities: Culturally informed research and clinical strategies., (pp. 223-245). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association, xvi, pp. 330.

- Ivey-Stephenson, A. Z., Crosby, A. E., Jack, S. P. D., Haileyesus, T., & Kresnow-Sedacca, M. (2017). Suicide trends among and within urbanization levels by sex, race/ethnicity, age group, and mechanism of death – United States, 2001-2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 66(18), 1–9.

- Rehkopf, D. H. & Buka, S. L. (2006). The association between suicide and the socioeconomic characteristics of geographical areas: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 36, 145–57.

- Turvey, C., Stromquist, A., Kelly, K., Zwerling, C., & Merchant, J. (2002). Financial loss and suicidal ideation in a rural community sample. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 106(5), 373–80.

- Mathew A, Saradamma R, Krishnapillai V, Muthubeevi SB. Exploring the Family factors associated with Suicide Attempts among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Qualitative Study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2021 Mar;43(2):113-118. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8313455/#bibr10-0253717620957113

- Lasrado RA, Chantler K, Jasani R, et al. Structuring roles, and gender identities within families explaining suicidal behavior in South India. Crisis, 2016; 37(3): 205–211.

- Macalli M, Tournier M, Galéra C, et al. Perceived parental support in childhood and adolescence and suicidal ideation in young adults: a cross-sectional analysis of the I-Share study. BMC Psychiatry, 2018; 18(1): 373.

- Brådvik L. Suicide Risk and Mental Disorders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Sep 17;15(9):2028. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6165520/

- Chu, J., Khoury, O., Johnson, M. Bahn, F., Bongar, B., and Goldblum, P. (2017). An Empirical Model and Ethnic Differences in Cultural Meanings Via Motives for Suicide. Journal of Clinical Psychology. Vol 73, Issue 10, pp. 1343-1359.

- Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jclp.22425

- National Institute of Mental Health “Major Depression”, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.dbsalliance.org/education/depression/statistics/

- O’Connor DB, Green JA, Ferguson E, O’Carroll RE, O’Connor RC. Cortisol reactivity and suicidal behavior: Investigating the role of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responses to stress in suicide attempters and ideators. Psych neuroendocrinology. 2017 Jan; 75:183-191.

- Suzuki H, Ohgidani M, Kuwano N, Chrétien F, Lorin de la Grandmaison G, Onaya M, Tominaga I, Setoyama D, Kang D, Mimura M, Kanba S, Kato TA. Suicide and Microglia: Recent Findings and Future Perspectives Based on Human Studies. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019; 13:31.

- De Berardis D, Fornaro M, Valchera A, Cavuto M, Perna G, Di Nicola M, Serafini G, Carano A, Pompili M, Vellante F, Orsolini L, Fiengo A, Ventriglio A, Yong-Ku K, Martinotti G, Di Giannantonio M, Tomasetti C. Eradicating Suicide at Its Roots: Preclinical Bases and Clinical Evidence of the Efficacy of Ketamine in the Treatment of Suicidal Behaviors. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 Sep 23;19(10)

- Hernández-Díaz Y, González-Castro TB, Tovilla-Zárate CA, Juárez-Rojop IE, López-Narváez ML, Pérez-Hernández N, Rodríguez-Pérez JM, Genis-Mendoza AD. Association between FKBP5 polymorphisms and depressive disorders or suicidal behavior: A systematic review and meta-analysis study. Psychiatry Res. 2019 Jan; 271:658-668.

- Biddle, N. Ellen, L, Reddy, K. (2020). Suicide and Self-harm monitoring. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/research-information/releases

- Ivey-Stephenson A, Demissie Z, Crosby A, et al. (2020) Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Suppl; 69(Suppl-1): 47–55. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/su/su6901a6.htm?s_cid=su6901a6_w

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022c), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. Feb 2022. Retrieved from http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html