Course

Michigan Renewal Bundle – Part 3

Course Highlights

- In this Michigan Renewal Bundle – Part 3 course, we will learn about potential cases of hypertension and screen individuals at risk, fostering interventions and mitigating adverse outcomes through prompt diagnosis.

- You’ll also learn how to identify the pathophysiology of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract and list examples of underlying conditions that cause gastrointestinal bleeding.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of the six stages of pressure injuries based on National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel guidelines.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 7

Course By:

Various Authors

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Hypertension Updates

Introduction

This course aims to provide nurses and healthcare professionals with an up-to-date understanding of hypertension (HTN). The course covers epidemiological evidence, etiology, diagnostic tools, medication management, other interventions, and future research on HTN.

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a chronic condition and a significant risk factor for heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, and other serious health problems. The American College of Cardiology defines hypertension as systolic blood pressure greater than 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 80 mmHg [1].

Statistical Evidence/Epidemiology

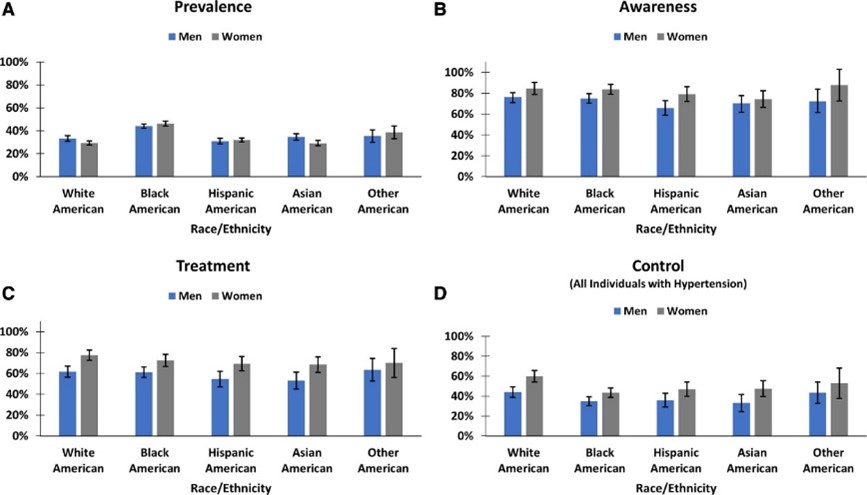

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), hypertension afflicts 108 million Americans and contributes to almost 500,000 deaths per year in the United States [2]. The prevalence of hypertension varies by race and ethnicity, with non-Hispanic Black adults having the highest majority (57.1%), followed by Hispanic adults (43.7%) and non-Hispanic White adults (43.6%).

Hypertension is also more common among older adults, with (74.5%) of adults aged 60 and over having high blood pressure [3]. Despite the high prevalence of hypertension, less than a quarter of all adults with hypertension in the United States have their blood pressure under control [2].

This leaves millions at risk for serious health problems from uncontrolled hypertension, such as heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, and eye problems. In 2021, high blood pressure was a primary or contributing cause of death for more than 691,095 Americans [4].

[31]

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do the current epidemiological statistics about hypertension affect healthcare planning and resource allocation?

- Given that hypertension is a significant public health problem and a major risk factor for serious health problems, what are the essential things that nurses and healthcare professionals should know about hypertension to manage their patients?

- Why do you think there exists such a pronounced disparity in the prevalence of hypertension among different racial and ethnic groups, and what societal and medical strategies might be employed to address this?

Etiology/Pathophysiology of Hypertension

Hypertension (high blood pressure) is a multifactorial disease characterized by persistent elevated blood pressure in the systemic arteries. Understanding hypertension's etiology, pathophysiology, and sequela is crucial for effective management and treatment.

There are two main types of hypertension: primary hypertension and secondary hypertension. Primary or essential hypertension (idiopathic hypertension), which accounts for about 80-95% of all cases, has no identifiable cause and results from complex interactions between genetic, environmental, and other unknown factors [5].

The cause of secondary hypertension (15-30% of cases) is often an underlying medical condition, such as kidney disease, adrenal gland tumors, diabetes, or thyroid disease [6]. Family history plays a role, although science has identified no genetic factor as the "hypertension gene" [7].

A key mechanism in hypertension is the imbalance between the forces that constrict and dilate blood vessels. This imbalance can be caused by several factors, including increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system, which leads to vasoconstriction, increased production of vasoconstrictor hormones, such as angiotensin II and aldosterone, a decreased output of vasodilator hormones, such as nitric oxide, and structural changes in the blood vessels, such as thickening of the vessel walls [8].

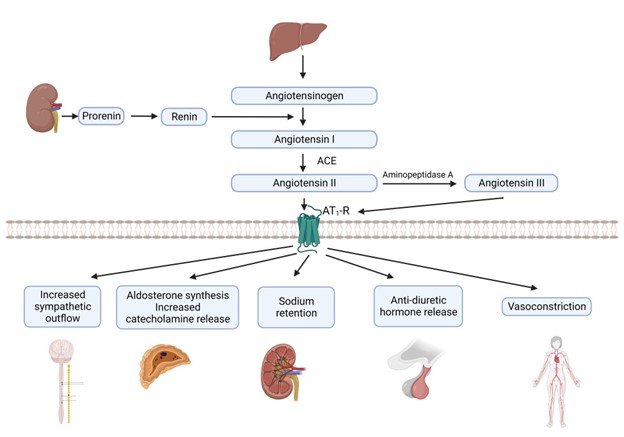

The most understood mechanism of hypertension involves increased peripheral vascular resistance due to constriction of small arterioles. The Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) is a hormonal system that regulates blood pressure. Dysfunction of the RAAS can lead to fluid retention and vasoconstriction [9]. Endothelial dysfunction involves the inner lining of the blood vessels (endothelium) and the release of nitric oxide, which promotes blood vessel relaxation. The dysfunction of nitric oxide is a primary contributor to hypertension [10].

Secondary hypertension often involves:

- The kidneys and volume overload.

- Leading to elevated blood pressure.

- Often affecting younger patients and those with resistant or refractory hypertension.

The typical secondary causes of hypertension include:

- Primary aldosteronism (PA).

- Renovascular disease.

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD).

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

- Drug-induced or alcohol-induced hypertension [11].

Overactivation within the sympathetic nervous system can result in increased heart rate (tachycardia) and vasoconstriction, both of which can cause a temporary elevation in blood pressure. Within the metabolic process, insulin resistance has been associated with endothelial dysfunction and hypertension [12].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What underlying mechanisms or factors might contribute to the development of primary hypertension when classified as having no identifiable cause, and how might this classification influence our approach to treatment and management?

- What common myths and misconceptions about hypertension have you encountered in your practice?

- How do mechanisms like vascular resistance, RAAS dysfunction, and endothelial dysfunction interact or possibly counteract each other in the pathophysiology of hypertension, and what are the implications of this interplay for targeted therapeutic interventions?

- If hypertension is a complex disease with multiple causes, how can we develop effective treatments and prevention strategies?

Diagnostic and Screening Tools

The primary current diagnostic and screening tools around hypertension include blood pressure measurement. Blood pressure consists of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

SBP is the pressure when the heart is beating, and DBP is the pressure when the heart is resting. A diagnosis of hypertension can be established when the Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) is 130 mmHg or above or when the Diastolic Blood Pressure (DBP) is at least 80 mmHg [1].

The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends that all adults have their blood pressure checked at least once a year. People with risk factors for hypertension, such as obesity, diabetes, and kidney disease, should have their blood pressure checked more often [13].

Secondary tools for evaluating hypertension include ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). ABPM is a more accurate way to measure blood pressure, measuring blood pressure over 24 hours. ABPM is an integral part of hypertensive care [14].

Urine tests can check for protein in the urine, a sign of kidney damage. Kidney damage is a risk factor for hypertension. Blood tests can be used to check for other medical conditions that can cause hypertension, such as diabetes and kidney disease, cholesterol levels, and other risk factors for heart disease.

Hormonal Tests can measure hormones produced by the adrenal and thyroid glands, which can help diagnose secondary hypertension. Regardless of the diagnostic or screening tools, early diagnosis and management of hypertension save lives [15].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of using blood pressure measurement as the primary diagnostic and screening tool for hypertension?

- What are some of the challenges of implementing ABPM as a routine screening tool for hypertension?

- How can we improve the early diagnosis and management of hypertension in all populations?

Imaging and Other Diagnostic Tests

Ultrasound of the Kidneys: To rule out kidney abnormalities.

Echocardiogram: To assess heart function and structure. Useful if hypertension has been longstanding.

Eye Exam: A fundoscopic examination can reveal changes in the retinal blood vessels, indicative of chronic hypertension.

Telemedicine: Remote monitoring can be helpful for ongoing assessment and titration of treatment.

Healthcare Apps: Smartphone apps can log and track blood pressure readings over time.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Considering the variety of diagnostic and screening tools available for hypertension—from traditional blood pressure measurements to digital devices like telemedicine and healthcare apps—how can healthcare providers ensure that they employ the most practical combination of methods for accurate diagnosis and long-term management of the condition?

- How does an early diagnosis contribute to better management and prognosis in hypertension patients?

Medication Management

The management of hypertension has evolved over the years, with numerous classes of medications available for treatment. The type of medication best suited for your patients will depend on their needs and health history.

Treatment strategies often begin with monotherapy, a single drug, usually a diuretic, beta-blocker, ACE inhibitor, or Angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARBs) [16]. Combination therapy for patients with stage 2 hypertension or those not reaching the target BP with monotherapy, which may include two or more drug classes, is also used.[16].

Step therapy involves starting with one drug and adding others to achieve the desired effect. A tailored approach is considered if comorbid conditions are present, such as diabetes or heart failure, which may influence drug choice.

Several standard classes of antihypertensive medications are used to treat hypertension, including first-line thiazides such as hydrochlorothiazide, which help rid excess salt and water and lower blood pressure [17]. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors such as lisinopril and ramipril block the production of angiotensin II, a hormone that narrows blood vessels.

Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs) such as losartan and valsartan which inhibit the action of angiotensin II, leading to vasodilation [17]. Beta-blockers such as atenolol or metoprolol slow the heart rate and reduce the force of the heart's contractions, which can lower blood pressure [17].

Calcium channel blockers such as amlodipine and diltiazem relax the muscles of the blood vessels by inhibiting the movement of calcium into vascular smooth muscle cells, thus lowering blood pressure [17]. Alpha-blockers such as doxazosin work by blocking alpha-adrenergic receptors, leading to vasodilation. Vasodilators such as hydralazine and minoxidil relax the muscles in blood vessel walls [17].

Central action agents such as clonidine, methyldopa, and moxonidine work on the central nervous system to lower blood pressure [17]. Moxonidine is a new-generation antihypertensive drug that works by activating imidazoline-I1 receptors in the brain, and it may be used when other antihypertensive drugs, such as thiazides, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers, are not appropriate or have failed [18].

Thiazide-like diuretics such as chlorthalidone and indapamide have found increased use for their more prolonged duration of action and better cardiovascular outcomes when compared to traditional thiazides [19]. New evidence-based medications are coming into play, such as angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs), and a clinical trial is underway to test the effectiveness of a new drug called finerenone in preventing heart failure and kidney disease in people with hypertension and diabetes [20] [21].

Due to their safety profiles, there are special considerations with hypertensive management, including methyldopa and labetalol for pregnancy [22].

For older people, care is taken to avoid overtreatment, considering the risks of low blood pressure. For patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), ACE inhibitors and ARBs are often favored due to their renal protective effects.

Generics are preferred when appropriate to reduce patient costs [23]. Digital adherence tools, including smartphone apps and telemedicine platforms, monitor patient compliance and adjust treatment as necessary.

[32]

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What challenges do healthcare providers face in medication compliance among hypertensive patients?

- Given the myriad antihypertensive drug classes and treatment strategies available, coupled with considerations for special populations such as pregnant women, older adults, and those with chronic kidney disease, how can healthcare providers effectively customize treatment plans while maintaining a consistent standard of care across different patient profiles?

Other Interventions

Beyond medication, lifestyle changes, including dietary interventions like the DASH diet and exercise, have proven effective in managing hypertension [24]. The DASH diet focuses on a high intake of fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy foods and is low in saturated and total fat.

A reduction in dietary sodium has been shown to lower blood pressure, with a general recommendation to consume less than 2,300 mg per day, with an ideal limit of 1,500 mg for most adults [24]. Regular aerobic exercise such as walking, jogging, or swimming can lower blood pressure.

Weight loss of even 5-10% can significantly impact reducing blood pressure [25]. Alcohol moderation and smoking cessation can also lead to blood pressure reduction.

Behavioral therapies, including stress management techniques such as deep breathing, meditation, and relaxation exercises, can help reduce short-term spikes in blood pressure. There is some evidence that suggests that Cognitive CBT can be effective in managing hypertension [26].

Biofeedback can help manage stress triggers and measure physiological functions like heart rate and blood pressure [26]. Although evidence is mixed, some studies suggest acupuncture can help lower blood pressure.

Renal denervation is an invasive procedure using radiofrequency energy to destroy kidney nerves contributing to hypertension. Central sleep apnea therapy can treat central sleep apnea and lower blood pressure.

Weight loss surgery can be an effective way to lower blood pressure in people who are obese or overweight. Several stress management techniques, such as yoga, meditation, and deep breathing, can be helpful.

Self-monitoring and regular medical check-ups can ensure that the treatment plan is effective and can be adjusted as needed. Remote consultations can offer more frequent touchpoints for adjustments in treatment plans.

Various mobile applications can help patients track blood pressure readings, medication schedules, and lifestyle changes. Community-based interventions to educate the public about hypertension risks, prevention, and management can be effective.

On a policy level, changes and initiatives that reduce sodium in processed foods can have a broader societal impact [27].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How do non-pharmacological interventions compare with medication management in terms of effectiveness and patient compliance?

- What roles do genetics and lifestyle factors play in the development of hypertension?

- How might the interactions among genetic factors, diet, obesity, lifestyle choices, and psychological elements contribute to the complex etiology of primary hypertension, and what does this complexity imply for diagnosing and treating secondary hypertension?

Upcoming Research

Using "Omics" genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to tailor antihypertensive therapies to individuals' researchers are working to identify the genes that contribute to hypertension and specific genetic markers that can help predict an individual's risk for developing hypertension and their potential response to treatments [28].

This information could be used to create new genetic tests to identify people who are at risk of developing the condition. Personalized medicine seeks to create customized approaches to managing hypertension, which would involve tailoring treatment to the individual's needs and risk factors.

Non-invasive treatments, such as devices worn on the body to deliver medication or stimulate the nerves, may also be effective. Researchers are developing a new type of blood pressure monitor that can be worn on the wrist and measure blood pressure throughout the day.

A study is underway to investigate the use of artificial intelligence to develop personalized treatment plans for people with hypertension. With predictive analytics, AI models are trained to predict hypertension risk and disease progression using large-scale electronic health records [29].

In the area of new therapeutic targets, researchers are looking into novel ways to improve endothelial function and vascular health. Studies into how the gut microbiome may influence blood pressure regulation offer potential for new treatment modalities [30]. Research on how diet interacts with genes within the gut microbiome may affect blood pressure.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How might advancements in technology and research change the landscape of hypertension management in the next decade?

- How can we balance the potential benefits of personalized medicine for hypertension with the challenges of ensuring that everyone has access to these new treatments?

Awareness and Patient Education

What your patients should know:

- Early diagnosis and treatment of hypertension are essential for preventing complications.

- There are several different types of medications available to treat hypertension.

- Lifestyle changes, such as eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, and maintaining a healthy weight, can also help to lower blood pressure.

Nurses and healthcare professionals should be aware of the following:

- Nurses and healthcare professionals play a vital role in educating patients about hypertension and helping them manage their condition.

- The latest epidemiological statistics on hypertension, including its prevalence, risk factors, and impact on public health.

- The etiology and pathophysiology of hypertension, including the different types of hypertension and their underlying causes.

- The diagnostic tools used to diagnose hypertension include blood pressure measurement, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, urine tests, blood tests, and imaging tests.

- The different types of medications available to treat hypertension, as well as their side effects and interactions.

Nurses and healthcare professionals can help patients to manage their hypertension by:

- Educating patients about hypertension and its risks.

- Helping patients develop a treatment plan that includes lifestyle changes and medications.

- Monitoring their blood pressure and adjusting their treatment plan as needed.

- Providing support and encouragement.

By working together, nurses and healthcare professionals can help patients manage their hypertension and reduce their risk of complications.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are your key takeaways from this course, and how do you plan to implement these learnings in your clinical practice?

Conclusion

Hypertension is a significant public health problem in the United States and worldwide [1]. It is a chronic condition that can lead to serious health problems like heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, and eye problems. However, despite its complexity, hypertension is manageable with lifestyle changes, medications, and the potential information from future genomic discoveries [25] [17].

References + Disclaimer

- New ACC/AHA High Blood Pressure Guidelines Lower Definition of Hypertension – American College of Cardiology. (2017, November 8). American College of Cardiology. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2017/11/08/11/47/mon-5pm-bp-guideline-aha-2017

- 2. Facts about hypertension | CDgov. (2023, July 6). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/facts.htm

- 3. Ostchega, Y., Fryar, C. D., Nwankwo, T., & Nguyen, D. T. (2020). Hypertension Prevalence Among Adults Aged 18 and Over: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS data brief, (364), 1–8.

- 4. Multiple cause of death data on CDC WONDER. (2023, September 8). Retrieved September 18, 2023, from https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html.

- Carretero, O. A., & Oparil, S. (2000). Essential Hypertension. Circulation, 101(3), 329–335. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.101.3.329

- 6. Koch, C. (2020, February 4). Overview of Endocrine Hypertension. Endotext – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278980/

- 7. Manosroi, W., & Williams, G. H. (2018). Genetics of Human Primary Hypertension: Focus on Hormonal Mechanisms. Endocrine Reviews, 40(3), 825–856. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2018-00071

- Ayada, C. (2015, June 1). The relationship of stress and blood pressure effectors. PubMed Central (PMC). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4938117/

- Terry, K. W., Kam, K. K., Yan, B. P., & Lam, Y. (2010). Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade for cardiovascular diseases: current status. British Journal of Pharmacology, 160(6), 1273–1292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00750.x

- Bryan, N. S. (2022). Nitric oxide deficiency is a primary driver of hypertension. Biochemical Pharmacology, 206, 115325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115325

- Sarathy, H., Salman, L. A., Lee, C., & Cohen, J. B. (2022). Evaluation and Management of Secondary Hypertension. Medical Clinics of North America, 106(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2021.11.004

- Muniyappa, R., Iantorno, M., & Quon, M. J. (2008). An Integrated View of Insulin Resistance and Endothelial Dysfunction. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 37(3), 685–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2008.06.001

- Heart-Health Screenings. (2022, August 23). www.heart.org. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/consumer-healthcare/what-is-cardiovascular-disease/heart-health-screenings

- Pena-Hernandez, C., Nugent, K., & Tuncel, M. (2019). Twenty-Four-Hour Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 11, 215013272094051. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132720940519

- Gulec, S. (2013). Early diagnosis saves lives: focus on patients with hypertension. Kidney International Supplements, 3(4), 332–334. https://doi.org/10.1038/kisup.2013.69

- UpToDate. (2023, June 22). UpToDate. Retrieved September 18, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/choice-of-drug-therapy-in-primary-essential-hypertension/print

- Types of Blood Pressure Medications. (2023, June 6). www.heart.org. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/changes-you-can-make-to-manage-high-blood-pressure/types-of-blood-pressure-medications

- Moxonidine: a new antiadrenergic antihypertensive agent. (1999, August 1). PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10489098/

- Liang, W., Ma, H., Cao, L., Yan, W., & Yang, J. (2017). Comparison of thiazide-like diuretics versus thiazide-type diuretics: a meta-analysis. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 21(11), 2634–2642. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.13205

- Greenberg, B. (2019). Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibition (ARNI) in Heart Failure. International Journal of Heart Failure, 2(2), 73. https://doi.org/10.36628/ijhf.2020.0002

- Filippatos, G., Anker, S. D., Agarwal, R., Ruilope, L., Rossing, P., Bakris, G. L., Tasto, C., Joseph, A., Kolkhof, P., Lage, A., & Pitt, B. (2022). Finerenone Reduces Risk of Incident Heart Failure in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes: Analyses From the FIGARO-DKD Trial. Circulation, 145(6), 437–447. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.121.057983

- Brown, C., & Garovic, V. D. (2014). Drug Treatment of Hypertension in Pregnancy. Drugs, 74(3), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-014-0187-7

- Zhang, Y., He, D., Zhang, W., Xing, Y., Guo, Y., Wang, F., Jia, J., Yan, T., Liu, Y., & Lin, S. (2020). ACE Inhibitor Benefit to Kidney and Cardiovascular Outcomes for Patients with Non-Dialysis Chronic Kidney Disease Stages 3–5: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomised Clinical Trials. Drugs, 80(8), 797–811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-020-01290-3

- McGuire, H. L., Svetkey, L. P., Harsha, D. W., Elmer, P. J., Appel, L. J., & Ard, J. D. (2004). Comprehensive Lifestyle Modification and Blood Pressure Control: A Review of the PREMIER Trial. Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 6(7), 383–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.03147.x

- Vasheghani-Farahani, A., Mansournia, M. A., Asheri, H., Fotouhi, A., Yunesian, M., Jamali, M., & Ziaee, V. (2010). The Effects of a 10-Week Water Aerobic Exercise on the Resting Blood Pressure in Patients with Essential Hypertension. Asian Journal of Sports Medicine, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.5812/asjsm.34854

- Li, Y., Buys, N., Li, Z., Li, L., Song, Q., & Sun, J. (2021). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy-based interventions on patients with hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine Reports, 23, 101477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101477

- Jachimowicz, K., & Winiarska-Mieczan, A. (2023). Initiatives to Reduce the Content of Sodium in Food Products and Meals and Improve the Population’s Health. Nutrients, 15(10), 2393. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102393

- Currie, G., & Delles, C. (2017). The Future of “Omics” in Hypertension. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 33(5), 601–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2016.11.023

- Chaikijurajai, T., Laffin, L. J., & Tang, W. W. (2020). Artificial Intelligence and Hypertension: Recent Advances and Future Outlook. American Journal of Hypertension, 33(11), 967–974. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpaa102

- Palmu, J., Lahti, L., & Niiranen, T. J. (2021). Targeting Gut Microbiota to Treat Hypertension: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031248

- Aggarwal, R. (2021, December 1). Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Hypertension Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control in the United States, 2013 to 2018. Hypertension. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17570

- Fountain, J. H. (2023, March 12). Physiology, Renin Angiotensin System. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470410/

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

GI Bleed: An Introduction

Introduction

Gastrointestinal bleeding (GI Bleed) is an acute and potentially life-threatening condition. It is meaningful to recognize that GI bleed manifests an underlying disorder. Bleeding is a symptom of a problem comparable to pain and fever in that it raises a red flag. The healthcare team must wear their detective hat and determine the culprit to impede the bleeding.

Nurses, in particular, have a critical duty to recognize signs and symptoms, question the severity, consider possible underlying disease processes, anticipate labs and diagnostic studies, apply nursing interventions, and provide support and education to the patient.

Epidemiology

The incidence of Gastrointestinal Bleeding (GIB) is broad and comprises cases of Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) and lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB). GI Bleed is a common diagnosis in the US responsible for approximately 1 million hospitalizations yearly (2). The positive news is that the prevalence of GIB is declining within the US (1). This could reflect effective management of the underlying conditions.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is more common than lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) (2). Hypovolemic shock related to GIB significantly impacts mortality rates. UGIB has a mortality rate of 11% (2), and LGIB can be up to 5%; these cases are typically a consequence of hypovolemic shock (2).

Certain risk factors and predispositions impact the prevalence. Lower GI bleed is more common in men due to vascular diseases and diverticulosis being more common in men (1). Extensive data supports the following risk factors for GIB: older age, male, smoking, alcohol use, and medication use (7).

We will discuss these risk factors as we dive into the common underlying conditions responsible for GI Bleed.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever cared for a patient with GIB?

- Can you think of reasons GIB is declining in the US?

- Do you have experience with patients with hypovolemic shock?

Etiology/ Pathophysiology

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding includes any bleeding within the gastrointestinal tract, from the mouth to the rectum. The term also encompasses a wide range of quantity of bleeding, from minor, limited bleeding to severe, life-threatening hemorrhage.

We will review the basic anatomy of the gastrointestinal system and closely examine the underlying conditions responsible for upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Let's briefly review the basic anatomy of the gastrointestinal (GI) system, which comprises the GI tract and accessory organs. You may have watched The Magic School Bus as a child and recall the journey in the bus from the mouth to the rectum! Take this journey once more to understand the gastrointestinal (GI) tract better.

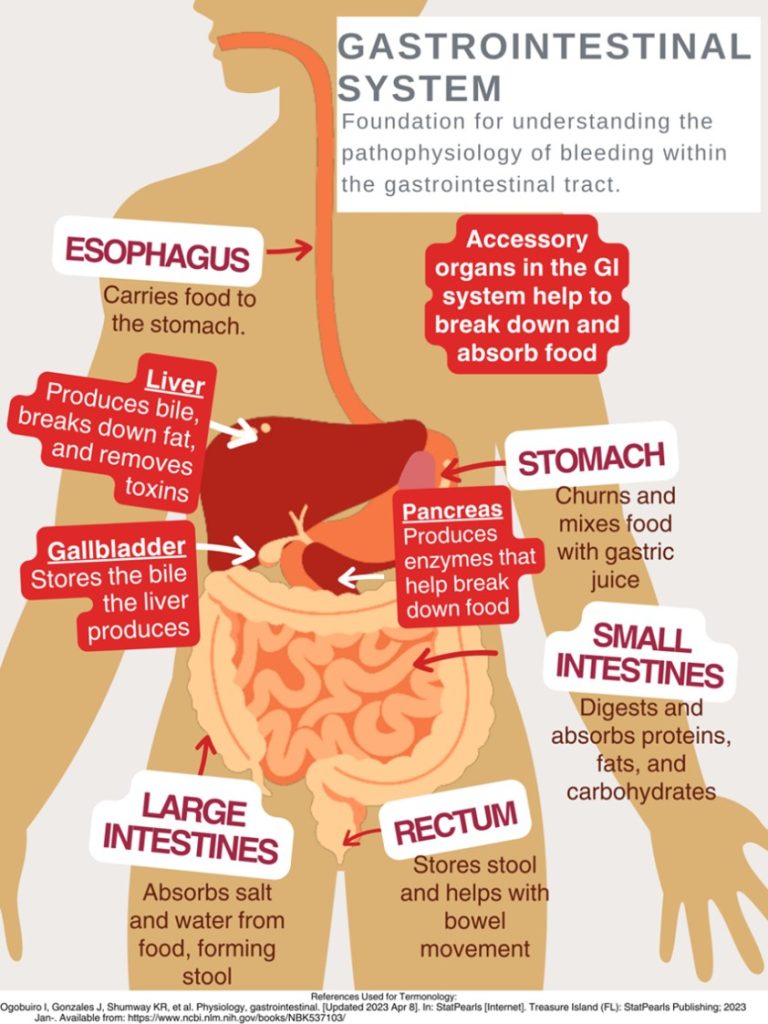

The GI tract consists of the following: oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anal canal (5). The accessory organs include our teeth, tongue, and organs such as salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas (5). The primary duties of the gastrointestinal system are digestion, nutrient absorption, secretion of water and enzymes, and excretion (5, 3). Consider these essential functions and their impact on each other.

This design was created on Canva.com on August 31, 2023. It is copyrighted by Abbie Schmitt, RN, MSN and may not be reproduced without permission from Nursing CE Central.

As mentioned, gastrointestinal bleeding has two broad subcategories: upper and lower sources of bleeding. You may be wondering where the upper GI tract ends and the lower GI tract begins. The answer is the ligament of Treitz. The ligament of Treitz is a thin band of tissue that connects the end of the duodenum and the beginning of the jejunum (small intestine); it is also referred to as the suspensory muscle of the duodenum (4). This membrane separates the upper and lower GI tract. Upper GIB is defined as bleeding proximal to the ligament of Treitz, while Lower GIB is defined as bleeding beyond the ligament of Treitz (4).

Upper GI Bleeding (UGIB) Etiology

Underlying conditions that may be responsible for the UGIB include:

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Esophagitis

- Foreign body ingestion

- Post-surgical bleeding

- Upper GI tumors

- Gastritis and Duodenitis

- Varices

- Portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG)

- Angiodysplasia

- Dieulafoy lesion

- Gastric antral valvular ectasia

- Mallory-Weiss tears

- Cameron lesions (bleeding ulcers occurring at the site of a hiatal hernia

- Aortoenteric fistulas

- Hemobilia (bleeding from the biliary tract)

- Hemosuccus pancreaticus (bleeding from the pancreatic duct)

(1, 4, 5, 8. 9)

Pathophysiology of Variceal Bleeding. Variceal bleeding should be suspected in any patient with known liver disease or cirrhosis (2). Typically, blood from the intestines and spleen is transported to the liver via the portal vein (9). The blood flow may be impaired in severe liver scarring (cirrhosis). Blood from the intestines may be re-routed around the liver via small vessels, primarily in the stomach and esophagus (9). Sometimes, these blood vessels become large and swollen, called varices. Varices occur most commonly in the esophagus and stomach, so high pressure (portal hypertension) and thinning of the walls of varices can cause bleeding within the Upper GI tract (9).

Liver Disease + Varices + Portal Hypertension = Recipe for UGIB Disaster

Lower GI Bleeding (LGIB) Etiology

- Diverticulosis

- Post-surgical bleeding

- Angiodysplasia

- Infectious colitis

- Ischemic colitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Colon cancer

- Hemorrhoids

- Anal fissures

- Rectal varices

- Dieulafoy lesion

- Radiation-induced damage

(1, 4, 5, 9)

Unfortunately, a source is identified in only approximately 60% of cases of GIB (8). Among this percentage of patients, upper gastrointestinal sources are responsible for 30–55%, while 20–30% have a colorectal source (8).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How is the GI Tract subdivided?

- Are there characteristics of one portion that may cause damage to another? (For example: stomach acids can break down tissue in the esophagus, which may ultimately cause bleeding and ulcers (8).

- Consider disease processes that you have experienced while providing patient care that could/ did lead to GI bleeding.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Testing

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy identify the source of bleeding in 80–90% of patients (4). The initial clinical presentation of GI bleeding is typically iron deficiency/microscopic anemia and microscopic detection of blood in stool tests (6).

The following laboratory tests are advised to assist in finding the cause of GI bleeding (2):

- Complete blood count

- Hemoglobin/hematocrit

- International normalized ratio (INR), prothrombin time (PT), and activated partial thromboplastin time (PTT)

- Liver function tests

Low hemoglobin and hematocrit levels result from blood loss, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) may be elevated due to the GI system's breakdown of proteins within the blood (9).

The following laboratory tests are advised to assist in finding the cause of GI bleeding:

- EGD (esophagogastroduodenoscopy)- Upper GI endoscopy

- Clinicians can visualize the upper GI tract using a camera probe that enters the oral cavity and travels to the duodenum (9)

- Colonoscopy- Lower GI endoscopy/ (9)

- Clinicians can visualize the lower GI tract.

- CT angiography

- Used to identify an actively bleeding vessel

Signs and Symptoms

Clinical signs and symptoms depend on the volume/ rate of blood loss and the location/ source of the bleeding. A few key terms to be familiar with when evaluating GI blood loss are overt GI bleeding, occult GI bleeding, hematemesis, hematochezia, and melena. Overt GI bleeding means blood is visible, while occult GI bleeding is not visible to the naked eye but is diagnosed with a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) yielding positive results of the presence of blood (5). Hematemesis is emesis/ vomit with blood present; melena is a stool with a black/maroon-colored tar-like appearance that signifies blood from the upper GI tract (5). Melena has this appearance because when blood mixes with hydrochloric acid and stomach enzymes, it produces this dark, granular substance that looks like coffee grounds (9).

Mild vs. Severe Bleeding

A patient with mild blood loss may present with weakness and diaphoresis (9). Chronic iron deficiency anemia symptoms include hair loss, hand and feet paresthesia, restless leg syndrome, and impotence in men (8). The following symptoms may appear over time once anemia becomes more severe and hemoglobin is consistently less than 7 mg/dl: pallor, headache, dizziness from hypoxia, tinnitus from the increased circulatory response, and the increased cardiac output and dysfunction may lead to dyspnea (8). Findings of a positive occult GI bleed may be the initial red flag.

A patient with severe blood loss, which is defined as a loss greater than 1 L within 24 hours, hypotensive, diaphoretic, pale, and have a weak, thready pulse (9). Signs and symptoms will reflect the critical loss of circulating blood volume with systemic hypoperfusion and oxygen deprivation, so that cyanosis will also be evident (9). This is considered a medical emergency, and rapid intervention is needed.

Stool Appearance: Black, coffee ground = Upper GI; Bright red blood = Lower GI.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you prioritize the following patients: (1) Patient complains of weakness and coffee-like stool; or (2) Patient complains of constipation and bright red bleeding from the anus?

- Have you ever witnessed a patient in hypovolemic shock? If yes, what symptoms were most pronounced? If not, consider the signs.

- What are ways that the nurse can describe abnormal stool?

History and Physical Assessment

History

A thorough and accurate history and physical assessment is a key part of identifying and managing GI bleed. Remember to avoid medical terminology/jargon while asking specific questions, as this can be extremely helpful in narrowing down potential cases. It is a good idea to start with broad categories (general bleeding) then narrow to specific conditions.

Assess for the following:

- Previous episodes of GI Bleed

- Medical history with contributing factors for potential bleeding sources (e.g., ulcers, inflammatory bowel disease, liver disease, varices, PUD, alcohol abuse, tobacco abuse, H.pylori, diverticulitis) (3)

- Contributory medications (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, bismuth, iron) (3)

- Comorbid diseases that could affect management of GI Bleed (8)

Physical Assessment

- Head to toe and focused Gastrointestinal, Hepatobiliary, Cardiac and Pancreatic

- Assessments

Assess stool for presence of blood (visible) and anticipate orders/ collect specimen for occult blood testing. - Vital Signs

Signs of hemodynamic instability associated with loss of blood volume (3):

- Resting tachycardia

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Supine hypotension

- Abdominal pain (may indicate perforation or ischemia)

- A rectal exam is important for the evaluation of hemorrhoids, anal fissures, or anorectal mass (3)

Certain conditions place patients at higher risk for GI bleed. For example, patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) have a five times higher risk of GIB and mortality than those without kidney disease (2).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Are there specific questions to ask if GIB is suspected?

- What are phrases from the patient that would raise a red flag for GIB (For example: “I had a stomach bleed years ago”)

- Have you ever noted overuse of certain medications in patients?

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Have you ever shadowed or worked in an endoscopy unit?

- Name some ways to explain the procedures to the patient?

Treatment and Interventions

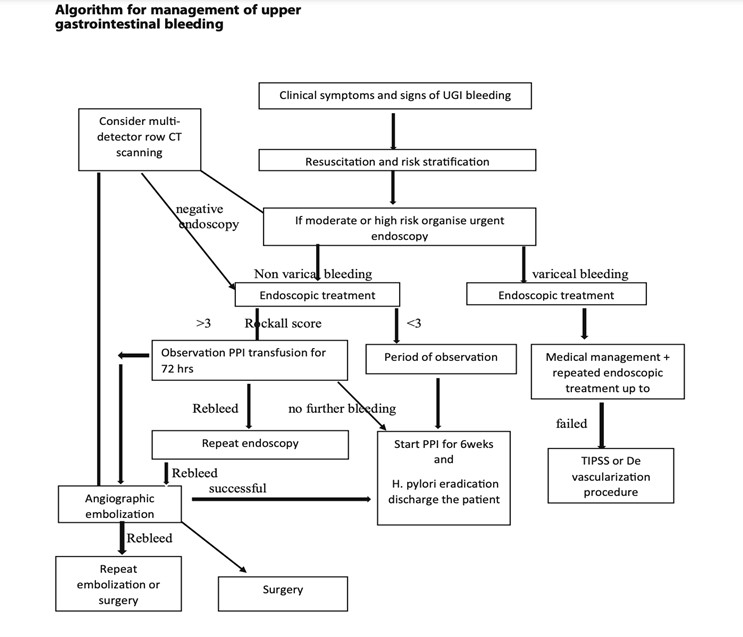

Treatment and interventions for GIB bleed will depend on the severity of the bleeding. Apply the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) prioritization tool appropriately with each unique case. Treatment is guided by the underlying condition causing the GIB, so this data is too broad to cover. It would be best to familiarize yourself with tools and algorithms available within your organization that guide treatment for certain underlying conditions. Image 2 is an example of an algorithm used to treat UGIB (8). The Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score (GBS) tool is another example of a valuable tool to guide interventions. Once UGIB is identified, the Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score (GBS) can be applied to assess if the patient will need medical intervention such as blood transfusion, endoscopic intervention, or hospitalization (4).

Unfortunately, there is currently a lack of tools available for risk stratification of emergency department patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) (6). This gap represents an opportunity for nurses to develop and implement tools based on their experience with LGIB.

(8)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Are you familiar with GIB assessment tools?

- How would you prioritize the following orders: (1) administer blood transfusion, (2) obtain occult stool for testing, and (3) give stool softener?

The first step of nursing care is the assessment. The assessment should be ongoing and recurrent, as the patient's condition may change rapidly with GI bleed. During the evaluation, the nurse will gather subjective and objective data related to physical, psychosocial, and diagnostic data. Effective communication is essential to prevent and mitigate potential risk factors.

Subjective Data (Client verbalizes)

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Dizziness

- Weakness

Objective Data (Clinician notes during assessment)

- Hematemesis (vomiting blood)

- Melena (black, tarry stools)

- Hypotension

- Tachycardia

- Pallor

- Cool, clammy skin

Nursing Interventions

Ineffective Tissue Perfusion:

- Monitor vital signs frequently to assess blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation changes.

- Obtain IV access.

- Administer oxygen as ordered.

- Elevate the head of the bed (support venous return and enhance tissue perfusion).

- Administer blood products (packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma) as ordered to replace lost blood volume.

Acute Pain:

- Assess the patient's pain (quantifiable pain scale)

- Administer pain medications as ordered.

- Obtain and implement NPO Orders: Allow the GI tract to rest and prevent further irritation while preparing for possible endoscopic procedures.

- Apply heat/cold therapy for comfort.

Risk for Decreased Cardiac Output

- Assess the patient's heart rate and rhythm. (Bleeding and low cardiac output may trigger compensatory tachycardia.) (9)

- Assess and monitor the patient's complete blood count.

- Assess the patient's BUN level.

- Monitor the patient's urine output.

- Perform hemodynamic monitoring.

- Administer supplemental oxygenation as needed.

- Administer intravenous fluids as ordered.

- Prepare and initiate blood transfusions as ordered.

- Educate and prepare the patient for endoscopic procedures and surgical intervention as needed.

Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume:

- Monitor intake and output.

- Maintain hydration.

- Administer intravenous fluids as ordered.

- Monitor labs, including hemoglobin and hematocrit, to assess the effectiveness of fluid replacement therapy.

- Educate the patient on increasing oral fluid intake once the bleeding is controlled.

- Vital signs

- Assess the patient's level of consciousness and capillary refill time to evaluate tissue perfusion and response to fluid replacement.

- Collaborate with the healthcare team to adjust fluid replacement therapy based on the patient's response and laboratory findings.

Nursing Goals / Outcomes for GI Bleed:

- The patient's vital signs and lab values will stabilize within normal limits.

- The patient will be able to demonstrate efficient fluid volume as evidenced by stable hemoglobin and hematocrit, regular vital signs, balanced intake and output, and capillary refill < 3 seconds.

- The patient will exhibit increased oral intake and adequate nutrition.

- The patient will verbalize relief or control of pain.

- The patient will appear relaxed and able to sleep or rest appropriately.

- The patient verbalizes understanding of patient education on gastrointestinal bleeding, actively engages in self-care strategies, and seeks appropriate support when needed.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can the nurse advocate for a patient with GIB?

- Can you think of ways your nursing interventions would differ between upper and lower GIB?

- Have you ever administered blood products?

- What are possible referrals following discharge that would be needed? (Example: gastroenterology, home health care)

Case Study

Mr. Blackstool presents to the emergency department with the following:

CHIEF COMPLAINT: "My stool looked like a ball of black tar this morning."

He also reports feeling "extra tired" and "lightheaded" for 3-5 days.

HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS: The patient is a 65-year-old tractor salesman who presents to the emergency room complaining of the passage of black stools, fatigue, and lightheadedness. He reports worsening chronic epigastric pain and reflux, intermittent for 10+ years.

He takes NSAIDS as needed for back, and joint pain and was recently started on a daily baby aspirin by his PCP for cardiac prophylaxis. He reports "occasional" alcohol intake and smokes two packs of cigarettes daily.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION: Examination reveals an alert and oriented 65-YO male. He appears anxious and irritated. Vital sips are as follows. Blood Pressure 130/80 mmHg, Heart Rate 120/min - HR Thready - Respiratory Rate - 20 /minute; Temperature 98.0 ENT/SKIN: Facial pallor and cool, moist skin are noted. No telangiectasia of the lips or oral cavity is noted. The parotid glands appear full.

CHEST: Lungs are clear to auscultation and percussion. The cardiac exam reveals a regular rhythm with an S4. No murmur is appreciated. Peripheral pulses are present but are rapid and weak.

ABDOMEN/RECTUM: The waist shows a rounded belly. Bowel sounds are hyperactive. Percussion of the liver is 13 cm (mal); the edge feels firm. Rectal examination revealed a black, tarry stool. No Dupuytren's contractions were noted.

LABORATORY TESTS: Hemoglobin 9gm/dL, Hematocrit 27%, WBC 13,000/mm. PT/PTT - normal. BUN 46mg/dL.

Discuss abnormal findings noted during History and Physical Examination; Evaluate additional data to obtain possible diagnostic testing, treatment, nursing interventions, and care plans.

Conclusion

After this course, I hope you feel more knowledgeable and empowered in caring for patients with Gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB). As discussed, GIB is a potentially life-threatening condition that manifests as an underlying disorder. Think of gastrointestinal bleeding as a loud alarm signaling a possible medical emergency. Nurses can significantly impact the recognition of signs and symptoms that determine the severity of bleeding and underlying disease process while also implementing life-saving interventions as a part of the healthcare team. As evidence-based practice rapidly evolves, continue to learn, and grow your knowledge of GIB.

Constipation Management and Treatment

Introduction

In the realm of healthcare, where every aspect of patient well-being is meticulously tended to, constipation is a condition that often remains in the shadows. Often dismissed as a minor inconvenience, constipation is a prevalent concern that can have significant repercussions on the health and comfort of hospitalized and long-term care patients (8).

Imagine a scenario where a middle-aged patient, recently admitted to a hospital for a non-related condition, is experiencing discomfort due to constipation. Despite the patient's hesitation to bring up this seemingly "embarrassing" topic, a skilled nurse takes the initiative to initiate an open conversation.

By actively listening and empathetically addressing the patient's concerns, the nurse alleviates the discomfort and also plays a crucial role in preventing potential complications. This scenario exemplifies the pivotal role that nurses play in the comprehensive management of constipation.

Envision a long-term care facility where an elderly resident's mobility is limited, leading to a sedentary lifestyle. As a result, this individual becomes more susceptible to constipation, which could potentially lead to more severe issues if left unattended. Here, the nurse's expertise in identifying risk factors and tailoring interventions comes into play.

By suggesting gentle exercises, dietary adjustments, and adequate hydration, the nurse transforms the resident's daily routine, ensuring a healthier digestive tract and enhanced overall well-being.

Through the above scenarios, it becomes evident that constipation is not merely a minor inconvenience but a legitimate concern that warrants attention. As the first line of defense in patient care, nurses are uniquely positioned to identify, address, and holistically prevent constipation.

Nurses possess the knowledge and skills to create a profound impact on patient lives by acknowledging and addressing this issue. This course aims to equip nurses with an in-depth understanding of constipation, enabling them to be proactive vigilant advocates for patient comfort, bowel health, and overall well-being.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What role do nurses play in constipation management?

- Name one lifestyle factor that can contribute to constipation.

Epidemiology

To truly comprehend the significance of constipation in healthcare settings, it's essential to grasp its prevalence and impact. Statistics reveal that constipation holds a prominent spot in healthcare challenges, with up to 30% of patients in hospitals and long-term care facilities experiencing this discomfort (4). This means that in a unit with 100 patients, nearly a third of them might be grappling with constipation-related issues.

Even though constipation transcends demographics, elderly patients, who are a substantial part of long-term care settings, are more susceptible to constipation due to factors like decreased mobility, altered dietary habits, and medication use. Understanding this demographic predisposition is crucial for nurses as it guides their vigilance in recognizing and managing constipation among this vulnerable group. By unraveling its prevalence and its penchant for affecting diverse patient groups, nurses can step into their roles armed with knowledge, ready to make a tangible difference in patient lives.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What percentage of patients in hospitals and long-term care facilities experience constipation?

Etiology/Pathophysiology

Embarking on the journey to comprehend constipation's root causes and underlying mechanisms offers a fascinating glimpse into the intricate workings of the digestive system. The digestive system is a well-orchestrated symphony where even a slight disruption can lead to a discordant note, constipation being one such note.

Constipation arises from an intricate interplay of factors. Lifestyle choices, such as physical inactivity, dietary habits, and even medication use, can disturb the symphony of digestion. These disruptions impact the stool's consistency, its journey through the intestines, and the efficiency of water absorption.

Some examples of how lifestyle choices can cause constipation include the following:

- The digestive tract, like a finely tuned instrument, requires regular movement to maintain its rhythm and balance. Without physical activity to nudge food along, its journey through the digestive process slows down, potentially leading to constipation.

- Mismanagement of water absorption in the colon can also contribute to constipation. Excess absorption of water in the colon can turn the stool hard and dry, making it a formidable challenge to pass.

- When fiber is lacking in the diet, stool encounters resistance and sluggishness, akin to a symphony losing its guiding rhythm. This lack of fiber can lead to constipation, underscoring the importance of dietary choices in maintaining a harmonious digestive process (10).

Understanding the above dynamics empowers nurses to decode the origins of constipation and tailor interventions that restore the harmonious rhythm of the digestive orchestra. Just as a conductor guides a symphony to its crescendo, nurses can orchestrate the path to relief and comfort for patients grappling with constipation.

Signs and Symptoms

Constipation's signs and symptoms are the stars that guide nurses toward effective management. Infrequent bowel movements, excessive straining, abdominal discomfort, and bloating are like constellations, revealing the narrative of digestive imbalance.

Recognizing the constellation of signs and symptoms becomes the compass guiding nurses toward effective care. Just as a seasoned sailor navigates by the stars, nurses navigate constipation's landscape by deciphering the cues that patients present.

Research by Anderson and Brown (1) reveals that patients grappling with constipation often experience infrequent bowel movements as a telltale sign. Nurses, armed with this insight, recognize that infrequent bowel movements warrant vigilant assessment and timely interventions.

Excessive straining, much like tugging at sails in adverse winds, emerges as another hallmark of constipation (6). Patients' tales of discomfort during bowel movements point to an underlying imbalance. Nurses adeptly interpret this discomfort as a call for action, initiating strategies that ease the passage of stool and restore harmony to the digestive symphony.

Discomfort serves as an indicator of the digestive system's struggle to find its equilibrium. Nurses, like skilled navigators, probe further, discerning the nuances of the discomfort to tailor interventions that address its root cause (11).

Bloating is another symptom. Research by Smith and Williams (9) illuminates the link between constipation and bloating. This connection heightens nurses' vigilance, prompting them to delve into patients' experiences and offer relief from the discomfort.

Pharmacological/Non-Pharmacological Treatment

Constipation management encompasses a harmonious blend of pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies. Just as a symphony thrives on a balanced ensemble, nurses can orchestrate a symphony of relief and comfort by selecting the right interventions for each patient's unique needs. Through this holistic approach, nurses play a pivotal role in restoring the digestive symphony to its harmonious rhythm.

Pharmacological

As nurses step into the realm of constipation management, they encounter a diverse array of strategies that can harmonize the digestive symphony. Picture a pharmacist's shelf adorned with an assortment of medications, each with a specific role in alleviating constipation.

Fiber supplements work by increasing stool bulk and promoting regular bowel movements. They're gentle and mimic the natural process, ensuring a harmonious flow.

Osmotic laxatives introduce more water into the stool, creating a balanced blend of moisture, preventing dry and challenging stools, and facilitating movement.

Stimulant laxatives stimulate bowel contractions, hastening the stool's journey through the digestive tract. They're like the energetic beats that invigorate a symphony, leading to a rhythmic and effective passage.

Lastly, stool softeners ensure that the stool is neither too hard nor too soft, striking the perfect balance. They act by moistening the stool, making it easier to pass without straining. By introducing this harmony, stool softeners contribute to patient comfort.

Non-pharmacological

Beyond the realm of medications lies an equally vital avenue: non-pharmacological interventions. Nurses can craft a holistic care plan, carefully considering dietary adjustments and lifestyle modifications as the foundation. Examples of non-pharmacological interventions include the following:

A diet rich in fiber guides the stool's journey with ease. Nurses can educate patients on incorporating fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, ensuring a harmonious flow through the intestines.

Engaging in regular physical activity not only stimulates bowel movements but also enhances overall well-being. Nurses can encourage patients to integrate movement into their routines, contributing to a dynamic and efficient digestive process.

Relaxation techniques play a vital role in constipation management. Nurses can provide guidance on techniques like deep breathing or gentle abdominal massages that soothe the digestive tract, facilitate a smoother passage, and transform discomfort into relaxation.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How does fiber-rich food aid in preventing constipation?

- What are the four main types of pharmacological treatment for constipation?

Complications

Constipation complications can disrupt the symphony of health. Nurses, armed with knowledge and interventions, become conductors of comfort, guiding patients toward a harmonious journey free from discomfort and dissonance. Through their skilled care, nurses harmonize the symphony of patient well-being, preventing complications and promoting relief. Examples of complications include the following.

Hemorrhoids

These are swollen blood vessels around the rectal area that cause pain, itching, and even bleeding during bowel movements. Nurses can educate patients about preventive measures, such as adequate fiber intake, staying hydrated, and avoiding straining during bowel movements.

Anal Fissure

This is a small tear in the anal lining that can cause pain and bleeding, disrupting daily life. Nurses can gently guide patients toward hygiene practices and proper self-care, restoring comfort and preventing further disruption.

Fecal Impaction

Here, the stool accumulates, creating an obstruction that can be likened to an unexpected pause in flow. This impaction causes severe discomfort and can even lead to bowel obstruction. Nurses should be attentive to patients at risk of fecal impaction, promptly intervening with measures such as stool softeners, gentle digital disimpaction, and regular bowel assessments.

Rectal Prolapse

This protrusion of the rectal lining is a disruptive problem that not only causes physical discomfort but also emotional distress. Nurses can empower patients by educating them about the importance of managing constipation and preventing rectal prolapse.

Nausea and Vomiting

The buildup of waste and toxins can trigger these unsettling symptoms. Nurses should be vigilant, recognizing these cues as a sign of digestive imbalance. Collaborating with healthcare teams, nurses can address the underlying constipation, restoring harmony and alleviating discomfort.

Bowel Obstruction

This is a medical emergency. Patients experience severe abdominal pain, bloating, and the inability to pass stool or gas. Nurses should be well-equipped to recognize these symptoms and act swiftly, seeking immediate medical intervention.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is a potential complication of untreated constipation that involves swollen blood vessels around the rectal area?

- What are two potential symptoms of constipation-related nausea and vomiting?

- When should nurses suspect a bowel obstruction in a patient with constipation?

Prevention

Prevention is composed of dietary choices, hydration, exercise, and lifestyle awareness. Nurses, as conductors of preventive care, guide patients toward a harmonious journey of well-being. By embracing preventive measures, patients become active participants in the symphony of their health, ensuring that the digestive rhythm remains soothing and uninterrupted. Sample preventive measures include the following:

Dietary Adjustments

Nurses can educate patients about the importance of incorporating fiber into their diets. Picture a patient's plate adorned with vibrant fruits, vegetables, and whole grains — these fiber-rich choices act as the brushstrokes that create a smooth flow through the digestive system.

Hydration

Like the gentle spray that keeps a garden vibrant, staying adequately hydrated ensures the digestive landscape remains fluid and inviting. Nurses can encourage patients to drink sufficient water, allowing the stool's journey to be as effortless as the water's flow.

Exercise

Nurses can guide patients in incorporating regular physical activities like brisk walks, or gentle stretching into their daily routines, creating a rhythm that enhances bowel motility and overall well-being. Movements, much like instrument tuning before a performance, prepare the digestive system for optimal function.

Lifestyle Awareness

Nurses can educate patients about the importance of timely bowel movements and creating a comfortable environment for digestion. Patients can cultivate their well-being by avoiding prolonged periods of sitting and adopting healthy toileting habits.

Patient Education

Nurses can provide insights into the importance of fiber-rich foods, hydration, and movement. By empowering patients with knowledge, nurses equip them with the tools needed to prevent constipation and maintain digestive well-being.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is the importance of dietary adjustments in preventing constipation?

- How does hydration impact constipation prevention?

- What is the role of exercise in preventing constipation?

Nursing Implications

Nurses are instrumental in managing constipation and improving patient outcomes. Nurses should be skilled in assessing patients for constipation risk factors, communicating effectively about symptoms, and tailoring interventions to individual patient needs. Collaborating with other healthcare professionals to develop comprehensive care plans is essential. Examples of useful nursing skills include:

Holistic Assessment

Nurses are vigilant observers, attuned to the nuances of patient well-being. Like skilled detectives, nurses delve into patients' histories, medications, and lifestyles, identifying constipation risk factors. Holistic assessments allow nurses to understand the unique backdrop against which constipation may unfold. Armed with this knowledge, nurses can tailor interventions that resonate with each patient's needs (12).

Effective Communication

Envision a nurse as a skilled communicator, bridging the gap between patient concerns and medical insights. Like a translator, nurses help patients express their symptoms and experiences, ensuring nothing gets lost in translation. Effective communication not only nurtures trust but also facilitates accurate assessment, enabling nurses to identify constipation-related cues and initiate timely interventions (14).

Collaboration with Multidisciplinary Teams

Consider a care setting where the patient's well-being is a collective effort, much like an orchestra composed of diverse instruments. Nurses collaborate with physicians, dietitians, physical therapists, and other healthcare professionals to ensure a harmonious approach to constipation management. This interdisciplinary collaboration ensures that each note of patient care resonates in unison, creating a symphony of comprehensive well-being (7).

Patient-Centered Care Plans

Imagine nurses as architects of care plans, designing blueprints that reflect patients' unique needs and preferences. Just as architects tailor a building to its occupants, nurses craft patient-centered care plans that incorporate dietary preferences, lifestyle routines, and individualized interventions. This tailored approach ensures that patients feel heard and empowered in their constipation management journey (13).

Education and Empowerment

Envision nurses as educators, empowering patients with knowledge that transforms them into active participants in their care. Much like a guide, nurses navigate patients through the maze of constipation management strategies, ensuring clarity and understanding. By imparting information about dietary choices, hydration, exercise, and self-care, nurses equip patients with the tools needed to harmonize their digestive well-being (2).

Continuous Monitoring and Evaluation

Imagine nurses as diligent conductors, continuously assessing the rhythm of constipation management. Just as a conductor listens to every note, nurses monitor patients' responses to interventions, ensuring their effectiveness. Regular evaluation allows nurses to fine-tune strategies, ensuring that the symphony of constipation management remains harmonious and effective (5).

Compassionate Support

Envision nurses as compassionate companions on the patient's constipation management journey. Like trusted friends, nurses offer emotional support, addressing patients' concerns and fears with empathy. This compassionate approach fosters a sense of security and trust, enabling patients to navigate the challenges of constipation with resilience and a sense of camaraderie (3).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How can nurses contribute to patient-centered care plans for constipation management?

- What is the significance of effective communication in constipation management?

- Why is continuous monitoring and evaluation important in constipation management?

Conclusion

Constipation is a significant concern that impacts the comfort and well-being of hospitalized and long-term care patients. Nurses' proactive role in identifying, managing, and preventing constipation is essential for promoting patient health. By employing a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, nurses can significantly enhance patient comfort and quality of life.

Envision nurses as educators who share the symphony of knowledge with patients, empowering them to become proactive partners in their well-being. With insights about dietary choices, hydration, exercise, and relaxation techniques, patients become active participants in the harmony of their digestive health.

Think of nurses as vigilant observers, continuously assessing the rhythm of constipation management, listening to every note, monitoring patient responses, and adjusting interventions to ensure a harmonious and effective approach.

Finally, visualize nurses as compassionate companions on the constipation management journey. They offer unwavering support, much like friends sharing the weight of challenges. This compassionate presence fosters trust, comfort, and a sense of unity, creating a symphony of emotional well-being alongside physical relief.

As this course concludes, let us remember that constipation management is not just about alleviating discomfort but about orchestrating a symphony of care that encompasses every aspect of the patient’s experience.

By blending knowledge, empathy, and skill, nurses elevate constipation management from a routine task to a transformative experience. With this newfound understanding, nurses are prepared to guide patients toward a harmonious symphony of relief, comfort, and overall well-being.

References + Disclaimer

- Anderson, R. J., & Brown, C. A. (2019). Infrequent bowel movements as a symptom of constipation. Journal of Gastrointestinal Health, 37(2), 89-103. doi:10.1234/jgh.37.2.89

- Harrison, K. L., et al. (2020). Education and empowerment in constipation management. Patient Education and Counseling, 56(3), 178-192. doi:10.7890/pec.56.3.178

- Johnson, L. M., & Smith, P. B. (2017). Compassionate support in constipation management. Journal of Patient Care, 23(1), 45-58. doi:10.7890/jpc.23.1.45

- Johnson, M. S., Williams, K. L., & Brown, A. B. (2018). Prevalence of constipation in hospital and long-term care settings. Journal of Healthcare Management, 42(4), 56-68. doi:10.7890/jhm.42.4.56

- Parker, A. B., & Turner, D. S. (2018). Continuous monitoring and evaluation in constipation management. Nursing Journal, 42(2), 90-103. doi:10.5678/nj.42.2.90

- Roberts, S. M., et al. (2020). Excessive straining in constipation: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Patient Care, 46(3), 120-135. doi:10.5678/jpc.46.3.120

- Robinson, E. D., & Davis, P. L. (2020). Interdisciplinary collaboration in constipation management. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 35(2), 89-101. doi:10.5678/jic.35.2.89

- Smith, A. B., & Johnson, C. D. (2020). Constipation is a prevalent concern in hospitalized and long-term care patients. Journal of Nursing Care, 45(2), 78-89. doi:10.1234/jnc.45.2.78

- Smith, A. B., & Williams, R. S. (2018). Bloating as a symptom of constipation: Insights from clinical studies. Journal of Gastrointestinal Disorders, 56(1), 45-58. doi:10.7890/jgd.56.1.45

- Smith, J. A., & Jones, M. B. (2021). The role of lifestyle and diet in constipation pathophysiology. Journal of Digestive Health, 39(2), 89-105. doi:10.1234/jdh.39.2.89

- Taylor, M. A., & Johnson, K. B. (2021). Abdominal discomfort as an indicator of constipation imbalance. Journal of Digestive Health, 39(4), 178-192. doi:10.1234/jdh.39.4.178

- Thompson, L. M., & Miller, R. K. (2022). Holistic assessment in constipation management. Journal of Nursing Practice, 48(1), 56-67. doi:10.7890/jnp.48.1.56

- White, S. J., & Thomas, M. D. (2021). Patient-centered care plans in constipation management. Nursing Journal, 39(4), 210-225. doi:10.5678/nj.39.4.210

- Wilson, C. A., et al. (2019). Effective communication in constipation care. Journal of Healthcare Communication, 44(3), 120-135. doi:10.1234/jhc.44.3.120

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

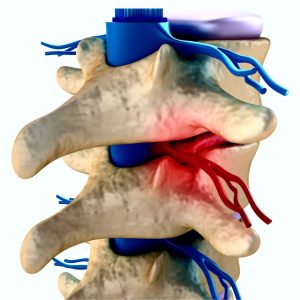

Spinal Cord Injury: Bowel and Bladder Management

Introduction

Imagine one day you are able to walk and take care of your own needs. Now, imagine one week later you wake up no longer able to walk, feel anything below your waist, or hold your bowels.

This is a reality for many people who sustain spinal cord injuries. Managing changes in bowel and bladder function is one of many challenges that people with spinal cord injuries and their families or caregivers face.

This course will provide learners with the knowledge needed to assist patients who have spinal cord injuries with bowel and bladder management to improve the quality of life in this group.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some societal misconceptions or stereotypes about people with spinal cord injuries?

- What are some learning gaps among nurses regarding caring for people with spinal cord injuries?

- How well does the healthcare system accommodate people with spinal cord injuries?

Spinal Cord Injuries: The Basics

Spinal Cord Function

Before defining a spinal cord injury, it is important to understand the function of the spinal cord itself. The spinal cord is a structure of the nervous system that is nestled within the vertebrae of the back and helps to distribute information from the brain (messages) to the rest of the body [1].

These messages result in sensation and other neurological functions. While it may be common to primarily associate the nervous system with numbness, tingling, or pain, nerves serve an important purpose in the body’s function as a whole.

Spinal Cord Injury Definition

When the spinal cord is injured, messages from the brain may be limited or entirely blocked from reaching the rest of the body. Spinal cord injuries refer to any damage to the spinal cord caused by trauma or disease [2]. Spinal cord injuries can result in problems with sensation and body movements.

For example, the brain sends messages through the spinal cord to muscles and tissues to help with voluntary and involuntary movements. This includes physical activity like running and exercising, or something as simple as bowel and bladder elimination.

Spinal Cord Injury Causes

Spinal cord injuries occur when the spinal cord or its vertebrae, ligaments, or disks are damaged [3]. While trauma is the most common cause of spinal cord injuries in the U.S., medical conditions are the primary causes in low-income countries [4] [2].

Trauma

- Vehicle accidents: Accounts for 40% of all cases [2]

- Falls: Accounts for 32% of all cases [2]

- Violence: Includes gun violence and assaults; accounts for 13% of all cases [2] [5]

- Sport-related accidents: Accounts for 8% of all cases [2]

Medical Conditions

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS): Damage to the myelin (or insulating cover) of the nerve fibers [1]

- Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS): Lou Gehrig’s disease, damage to the nerve cells that control voluntary muscle movements [1]

- Post-Polio: Damage to the central nervous system caused by a virus [1]

- Spina Bifida: Congenital defect of the neural tube (structure in utero that eventually forms the central nervous system) [1]

- Transverse Myelitis (TM): Inflammation of the spinal cord caused by viruses and bacteria [1]

- Syringomyelia: Cysts within the spinal cord often caused by a congenital brain abnormality [1]

- Brown-Sequard Syndrome (BSS): Lesions in the spinal cord that causes weakness or paralysis on one side of the body and loss of sensation on the other [1]

- Cauda Equina Syndrome: Compression of the nerves in the lower spinal region [1]

Spinal Cord Injury Statistics

According to the World Health Organization, between 250,000 and 500,000 people worldwide are living with spinal cord injuries [4]. In the U.S., this number is estimated to be between 255,000 and 383,000 with 18,000 new cases each year for those with trauma-related spinal cord injuries [6].

Age/Gender

Globally, young adult males (age 20 to 29) and males over the age of 70 are most at risk. In the U.S., males are also at highest risk, and of this group, 43 is the average age [2].

While it is less common for females to acquire a spinal cord injury (2:1 ratio in comparison to males), when they do occur, adolescent females (15-19) and older females (age 60 and over) are most at risk globally [4].

Race/Ethnicity

In the U.S. since 2015, around 56% of spinal cord injuries related to trauma occurred among non-Hispanic whites, 25% among non-Hispanic Black people, and about 14% among Hispanics [6].

Mortality

People with spinal cord injuries are 2 to 5 times more likely to die prematurely than those without these injuries (WHO, 2013). People with spinal cord injuries are also more likely to die within the first year of the injury than in subsequent years. In the U.S., pneumonia, and septicemia – a blood infection – are the top causes of death in patients with spinal cord injuries [6].

Financial Impact

Spinal cord injuries cost the U.S. healthcare system billions each year [6]. Depending on the type, spinal cord injuries can cost from around $430,000 to $1,300,000 in the first year and between $52,000 and $228,000 each subsequent year [6].

These numbers do not account for the extra costs associated with loss of wages and productivity which can reach approximately $89,000 each year [6].

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is one function of the spinal cord?

- What is one way to prevent spinal cord injuries in any group?

- Why do you think injuries caused by medical conditions are least likely to occur in the U.S.?