Course

Kentucky APRN Bundle

Course Highlights

- In this Kentucky APRN Bundle, we will learn about how advanced practice registered nurses (APRNS) can engage in safe prescribing practices in the care of patients with opioid use disorders.

- You’ll also learn statistics on addiction disorders in the United States and the state of Kentucky.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding common side effects, including severe possible side effects, of SSRIs

About

Pharmacology Contact Hours Awarded: 5

Course By:

Abbie Schmitt RN, MSN-Ed

Sadia A. MPH, MSN, WHNP-BC

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Kentucky Addiction Disorders

Introduction

The United States is facing an epidemic of opioid-related mortality and morbidity that has an unparalleled impact. Drug overdoses are the leading cause of accidental deaths in the U.S. (13). Roughly two-thirds of drug overdose deaths were caused by opioids – both legal and illicit (18). There are two intertwined epidemics: the excessive use of opioids for both legal and illicit purposes, and unprecedented levels of consequent opioid use disorder (OUD).

Addiction remains one of the most critical public health and safety issues facing the Commonwealth of Kentucky (8). There is hope on the horizon for those in Kentucky who are impacted by addiction disorders. The data and statistics suggest that the interventions established are having a meaningful impact. Kentucky had a decrease of over 5% of overdose deaths in 2022 from 2021. Significant legislation has been implemented to battle this crisis within the state of Kentucky.

As we explore addiction disorders, it is meaningful to understand the pharmacology of the most common opioids and the pharmacokinetics of Fentanyl to fully understand how a common treatment, Methadone, is effectively used.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What ethical consideration should APRNs be aware of when prescribing opioids?

- How can APRNs balance pain management needs with the risk for addiction?

- What is the most commonly misused opioid in our country?

- Can you think of any commonly used medications that treat addiction disorders?

Etiology and Statistics on Addiction Disorders in Kentucky

Opioids are the primary culprit of drug overdose deaths. In 2000, opioid overdoses represented 48% of drug overdose deaths in the U.S.; by 2021, they represented 75% of these deaths (11).

The Office of the State Medical Examiner (OSME) and toxicology reports submitted by Kentucky coroners state that 90% of deaths in 2022 involved opioids (13).

It is important to look at trends in data. Recent statistics of addiction disorders in Kentucky:

- In 2020, there were 1,964 overdose deaths in KY

- In 2021, there were 2,250 overdose deaths in KY (14.5% increase from 2020)

- In 2022, there were 2,135 overdose deaths (5% decrease from 2021)

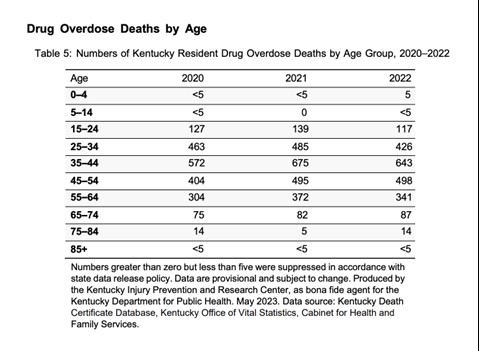

The Office of Drug Control Policy (ODCP) reports that 90% of deaths in 2022 involved opioids. The most prevalent drug contributing to overdose deaths is fentanyl, accounting for 72.5% nationwide in 2022 [See Figure 1]. In Kentucky, of the 2,135 overdose deaths in 2022, 1,548 (73%) were identified from toxicology testing (11). The age group with the greatest number of drug overdose deaths in Kentucky in 2022 included those between the ages of 35 and 44 [See Figure 2] (11).

Figure 1. Kentucky Fentanyl-Related Drug Overdose Deaths in 2022 (11)

Figure 2. Kentucky Drug Overdose Deaths by Age 2020-2022 (11)

Terminology Related to Addiction and Misuse

These terms are similar, but providers and clinicians should be aware of the differences (6).

- Addiction – the constant need for a drug despite harmful consequences.

- Pseudoaddiction – constant fear of being in pain, hypervigilance; usually there is a resolution with pain resolution.

- Dependence – physical adaptation to a medication where it is necessary for normal function and withdrawal occurs with lack of the medication.

- Tolerance – lack of expected response to a medication resulting in an increase in dose to achieve the same pain relief, resulting from central nervous system (CNS) adaptation to the medication over time.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you discuss the demographics that have the highest number of overdose deaths?

- How would you describe the statistics on Kentucky addiction disorders relating to opioids?

- Can you summarize the terms addiction, psuedoaddiction, dependence, and tolerance?

- Have overdose deaths relating to opioids increased or decreased over the past 20 years?

Opioid Use Disorder (OUD)

An opioid use disorder (OUD) is defined as a problematic pattern of opioid use that leads to serious impairment or distress (5).

In the late 1990s, prescription opioid use increased in all regions of the U.S. Unregulated prescription opioid use was promoted, in large part by the pharmaceutical industry (5). Misuse and diversion of these medications became widespread; by 2017, an estimated 1.7 million people in the U.S. suffered from substance use disorders related to prescription opioid pain medications (5).

The DSM-5 Criteria is an excellent guide for diagnosing OUD. To be eligible for methadone treatment, patients must meet DSM-5 criteria for opioid use disorder. According to the DSM-5, the presence of at least two of the following symptoms indicates OUD (1).

- Opioids are often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended

- There is persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control opioid use

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the opioid, use the opioid, or recover from its effects

- Craving or a strong desire to use opioids

- Recurrent opioid use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home

- Continued opioid use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of opioids

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of opioid use

- Recurrent opioid use in situations in which it is physically hazardous

- Continued use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by opioids

- Tolerance as defined by either of the following:

- Need for markedly increased amounts of opioids to achieve intoxication or desired effect

- Markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of opioid

- Withdrawal as manifested by either of the following:

- Characteristic opioid withdrawal syndrome.

- Same (or a closely related) substance is taken to relieve or avoid withdrawal

The severity of OUD is defined as (1):

MILD: The presence of 2 to 3 symptoms

MODERATE: The presence of 4 to 5 symptoms

SEVERE: The presence of 6 or more symptoms

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How is Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) defined?

- What is the DSM-5 criteria for this diagnosis?

- How can clinicians determine if opioids are having an impact on a patient’s functional level?

- Can you think of reasons it is important to appropriately diagnose the disorder prior to prescribing medications for the treatment?

Opiates and Opioids

Opiates are chemical compounds that are extracted or refined from natural plant matter (poppy sap and fibers).

Examples of opiates:

- Opium

- Morphine

- Codeine

- Heroin

Opioids are chemical compounds that generally are not derived from natural plant matter. Most opioids are synthesized.

Though a few opioid molecules — hydrocodone (e.g., Vicodin), hydromorphone (e.g., Dilaudid), oxycodone (e.g., Oxycontin, Percocet) — may be partially synthesized from chemical components of opium, other popularly-used opioid molecules are designed and manufactured in laboratories.

The pharmaceutical industry has created more than 500 different opioid molecules.

Common opioids used in the U.S. for treatment of pain:

- Fentanyl/fentanyl (e.g., Ultiva, Sublimaze, Duragesic patch)

- Dextropropoxyphene (e.g., Darvocet-N, Darvon)

- Hydrocodone (e.g., Vicodin)

- Oxycodone (e.g., Oxycontin, Percocet)

- Oxymorphone (e.g., Opana)

- Meperidine (e.g., Demerol)

Pharmacokinetics of Fentanyl

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid agonist that is 80-100 times stronger than morphine and is often added to heroin to increase its potency (6). It can cause severe respiratory depression and death, particularly when mixed with other drugs or alcohol. It has high addiction potential.

Drug Class

Opioid, narcotic agonist (Schedule II).

Uses

Pain relief, preop medication; adjunct to general or regional anesthesia. Management of chronic pain (transdermal).

Mechanism of Action

Opioids can be classified according to their effect on opioid receptors and can be considered as agonists, partial agonists, antagonists, and agonist-antagonists.

- Agonists – interact with an opioid receptor to produce a maximal response from that receptor.

- Antagonists – bind to receptors but produce no functional response, while at the same time preventing an agonist from binding to that receptor (naloxone).

- Partial agonists – bind to receptors but elicit only a partial functional response regardless of the amount of drug administered

- Agonist-antagonists – act as agonist to a certain opioid receptor, but have antagonist activity to another opioid receptor

Fentanyl is an μ-opioid agonist that binds to μ-opioid G-protein-coupled receptors, which prevents the release of pain neurotransmitters by decreasing the cellular calcium level. These receptors bind opioids, so they are also commonly referred to as mu-opioid receptors (MORs).

The connection between the receptor and the first stage of signal transduction becomes established through the G proteins (alpha, beta, and gamma subunits). The main targets of G proteins include the adenyl cyclase, which is the enzyme responsible for the formation of the second messenger, and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) (10).

The phospholipase C is the enzyme responsible for the formation of several ion channels such as the calcium and potassium channels (10). Essentially, GPCRs can directly control the activity of ion channels through mechanisms that do not involve the second messengers. Opioids reduce neuronal excitability by opening the G protein-dependent and rectifying potassium (irk) channels (GIRK) and subsequent cell membrane hyperpolarization (10).

The opening of the channel occurs by the direct interaction between the subunits of the G protein and the potassium ion channel.

Endogenous and exogenous opioids operate through both inhibitory and excitatory action at the presynaptic and postsynaptic sites. In particular, the MORs interact with a G protein of the inhibitory type (10).

In the resting state, G-alpha-beta-gamma complex and the subunit α causes the bind, guanosine diphosphate (GDP). The binding of the opioid agonist (endogenous or exogenous) to the extracellular N-terminus domain of the MOR induces dissociation of GDP from the G-alpha subunit, which is replaced by guanosine triphosphate (GTP).

Because the enzymatic GTP turnover lasts approximately two to five minutes, a new signal may find the receptor still not ready to respond, so the regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) protein speeds up the GTP hydrolysis up to 100-fold; this protein binds the G-alpha subunit and removes the active G-alpha-GTP and beta-gamma species (10).

MORs are present in the CNS and are the most highly expressed of all opioid receptors. These receptors are expressed in neurons throughout the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and in different regions or the brain (10). Within the spinal cord, MORs are localized (presynaptic and postsynaptic) and receive sensory information from primary afferent nerve fibers innervating the skin and deeper tissues of the body (10).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How are the mechanisms of action different between agonists, partial agonists, antagonists, and agonist-antagonists?

- Can you describe how fentanyl prevents the release of pain neurotransmitters?

- Where are MORs located in the body?

- How much more potent is fentanyl than morphine?

Fentanyl Pharmacodynamics/Kinetics

- Onset of action for adults:

- IM: 7 to 8 minutes

- IV: Almost immediate (maximal analgesic and respiratory depressant effects may not be seen for several minutes)

- Transdermal patch (initial placement): 6 hours

- Transmucosal: 5 to 15 minutes

- Duration:

- IM: 1 to 2 hours

- IV: 0.5 to 1 hour

- Distribution: Highly lipophilic, redistributes into muscle and fat

- Note: IV fentanyl exhibits a 3-compartment distribution model

- Changes in blood pH may alter ionization of fentanyl and affect its distribution between plasma and CNS

- Vdss: Adults: 4 to 6 L/kg

- Protein binding: 79% to 87%, primarily to alpha-1 acid glycoprotein; also binds to albumin and erythrocytes.

- Metabolism: Hepatic, primarily via CYP3A4 by N-dealkylation and hydroxylation to other inactive metabolites.

- Half-life elimination:

- IV: Adults: 2 to 4 hours; when administered as a continuous infusion, the half-life prolongs with infusion duration due to the large volume of distribution (Sessler 2008)

- Sub-Q bolus injection: 10 hours

- Transdermal device: Terminal: ~16 hours

- Transdermal patch: 20 to 27 hours

- Transmucosal products: 3 to 14 hours (dose dependent)

- Intranasal: 15 to 25 hours (based on a multiple-dose pharmacokinetic study when doses are administered in the same nostril and separated by a 1-, 2-, or 4-hour time lapse)

- Buccal film: ~14 hours

- Buccal tablet: 100-200 mcg: 3 to 4 hours; 400 to 800 mcg: 11 to 12 hours

- Time to peak:

- Buccal film: 0.75 to 4 hours (median: 1 hour)

- Buccal tablet: 20 to 240 minutes (median: 47 minutes)

- Lozenge: 20 to 480 minutes (median: 20 to 40 minutes)

- Intranasal: Median: 15 to 21 minutes

- SubQ bolus injection: 10 to 30 minutes (median: 15 minutes)

- Sublingual spray: 10 to 120 minutes (median: 90 minutes)

- Sublingual tablet: 15 to 240 minutes (median: 30 to 60 minutes)

- Transdermal patch: 20 to 72 hours; steady state serum concentrations are reached after two sequential 72-hour applications

- Excretion: Urine 75%; feces ~9%

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What is the time of onset for the various forms of fentanyl?

- How is knowing the half-life meaningful when prescribing fentanyl?

Fentanyl Side Effects

- IV: Postop drowsiness, nausea, vomiting.

- Transdermal (10%– 3%): Headache, pruritus, nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, dyspnea, confusion, dizziness, drowsiness, diarrhea, constipation, decreased appetite (12)

Occasional:

- IV: Postop confusion, blurred vision, chills, orthostatic hypotension, constipation, difficulty urinating.

- Transdermal (3%–1%): Chest pain, arrhythmias, erythema, pruritus, syncope, agitation, skin irritations (12)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some common side effects of fentanyl?

- Can you name some management strategies for these side effects?

Fentanyl Adverse Effects

Overdose or too-rapid IV administration may produce severe respiratory depression, skeletal/thoracic muscle rigidity. This muscle rigidity may lead to apnea, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, cold/clammy skin, cyanosis, coma. Tolerance to analgesic effect may occur with repeated use (12).

Transdermal Fentanyl

Mechanism of Action

As mentioned, Fentanyl is nearly 100 times more potent than morphine, resulting in an estimated conversion ratio of 1 to 100 to provide an equal degree of analgesia. It has low molecular weight, high potency, and lipid solubility, which makes it ideal for use with the transdermal route.

Fentanyl is a 4-anilidopiperidine compound, it exerts its effect by acting as a high-affinity agonist on selective Mu-opioid receptors in the brain (17). It also has effects on delta and kappa receptors. The activation of Mu-opioid receptors causes analgesia and stimulates areas of the brain responsible for addictive potential.

The transdermal route eliminates the first-pass metabolism of fentanyl by the liver, increasing bioavailability to 90%, making it possible to use lower doses of the drug, thus reducing the incidence of adverse effects.

Fentanyl can be detected in serum after about one to two hours after first application but does not reach the therapeutic index until approximately 12 to 16 hours due to the need for fentanyl to saturate the epidermis before more efficient absorption (17). The patches are designed to deliver fentanyl at a constant rate.

Fentanyl is available in various doses: 12, 25, 50, 75, and 100 mcg/hour; requiring replacement every 72 hours.

Fentanyl metabolism occurs via cytochrome P450 (CYP34A) enzymes into inactive metabolites; hence drugs that enhance or inhibit cytochrome P450 will affect its metabolism (17).

The elimination half-life after patch removal is 13 to 22 hours; this is due to the slow release of fentanyl from the skin (16).

Several studies have shown that when compared to sustained-release oral morphine (SROM), transdermal fentanyl has a 30% lower incidence of adverse effects such as constipation and sedation (p<0.05). (16)

Administration

The patch has an adhesive side that contains an active ingredient that must be applied directly flat on the skin, and it should be applied to intact, clean, and healthy skin. Skin with scars, rashes, or open wounds should be avoided. Areas with excess hair require clipping if applying the patch in that location.

The ideal areas to apply the adhesive patch are the chest, back, and arms. Patches should not be applied consecutively in the same location (17). The transdermal fentanyl patch must be removed after 72 hours. Proper disposal is important to avoid intentional abuse and misuse of the discarded patch.

Adverse Effects

The most common adverse drug reactions of transdermal fentanyl are nausea, vomiting, and constipation (17). Adverse side effects are manageable with stool softeners and antiemetics. There is a higher incidence of respiratory depression in patients who have not previously been exposed to opioid analgesics. Additional adverse effects include rash and erythema at the application site of the patch that abates after removal or with antihistamine therapy (17). Hypoventilation has been noted as an adverse effect.

Withdrawal symptoms of transdermal fentanyl may cause adverse side effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and shivering. These symptoms may occur when decreasing dosage, abrupt cessation of use, or changing to an alternative opioid medication (17).

Contraindications

Contraindications of transdermal fentanyl include patients who experience hypoventilation, respiratory compromise (including acute or severe asthma) or respiratory depression should not take transdermal fentanyl. Also, fentanyl transdermal should be avoided during the acute postoperative pain period for short term pain control, intermittent pain control, or mild pain (17).

Pediatric patients under 12 or children under 50 kgs and under 18 should not use this drug. Avoid use in patients with a history of sensitivity or reactions to adhesives.

Prescriber Monitoring

Fentanyl is an extremely potent opioid and requires prescriber monitoring to maintain a safe therapeutic concentration. The gold standard method of assessing fentanyl concentration is Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. A blood concentration of 0.6 ng/ml to 3.0 ng/ml is appropriate for analgesia.

Monitoring Fentanyl is increasingly important when the patient is taking multiple medications. Drugs that are important review carefully are those which inhibit CYP3A4 metabolism, which causes an increase in Fentanyl concentration and can lead to toxicity. Examples of these drugs include azole class antifungals and macrolide antibiotics (17). CYP3A4 inducers, such as rifampin, phenytoin, and carbamazepine, may also reduce the level of fentanyl to a non-therapeutic level (17).

Antidote for Fentanyl: Naloxone

Nursing Considerations (12):

- Prepare: Resuscitative equipment and opiate antagonist (naloxone 0.5 mcg/kg) should be available for initial use.

- Establish baseline blood pressure, pulse rate, and respirations.

- Assess type, location, intensity, duration of pain.

- Assess fall risk and implement appropriate precautions.

- Assist with ambulation and encourage patient to turn, cough, deep breathe every two hours.

- Monitor respiratory rate, B/P, heart rate, oxygen saturation.

- Assess for relief of pain.

- For patients with prolonged high-dose use, continuous infusions (critical care, ventilated patients), clinicians should consider weaning the drip gradually or transitioning to a fentanyl patch to decrease symptoms of opiate withdrawal.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you describe how increasing knowledge among prescribers can help to battle the opioid crisis?

- What are some contraindications when prescribing fentanyl?

- Why is it important to document the reason for prescribing this drug?

- How can knowledge of the mechanisms of action of opioids help to guide understanding of treatments for opioid abuse disorders?

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) for OUD

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is the use of medications, in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies, in the treatment of opioid use disorders (OUD). The goal is sustained recovery. Often, individuals have actual pain and became dependent on prescription narcotic drugs, then switch to illicit opioids or the opiate heroin when the medically supplied narcotics run out.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has only approved three medication assisted treatments (MATs) for opioid use disorder (OUD): methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.

We will discuss the pharmacokinetics of Methadone in this course.

FDA-approved methadone products approved for the treatment of OUD include:

- Dolophine (methadone hydrochloride) tablets

- Methadose (methadone hydrochloride) oral concentrate

Buprenorphine and methadone have been shown to decrease mortality among those with OUD. A recent study reported that buprenorphine was associated with a lower risk of overdose during active treatment compared to post-discontinuation.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you name the drugs that are approved by the FDA for the treatment of OUD?

- How can partnerships between policy makers and healthcare providers enhance MATs?

- How would you describe your experience in addiction treatment programs?

- Have you ever administered methadone in your nursing practice?

Methadone

Methadone is a medication approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat OUD, as well as for management of chronic pain. Methadone is safe and effective when taken as prescribed. Methadone is a component of a comprehensive treatment plan, which includes counseling and other behavioral health therapies to provide patient-centered care.

Definition

Methadone, a long-acting opioid agonist, it can help relieve cravings and withdrawal, while also blocking the effects of opioids (15). It is available in liquid, powder, and diskettes forms. Patients taking methadone to treat OUD must receive the medication under the supervision of a medical provider, but after a period of stability and consistent compliance, patients may be allowed to take methadone at home between program visits (15).

Drug Class

Opioid agonist (Schedule II). CLINICAL: Opioid analgesic. Opioid dependency management. (12)

Uses

Methadone is a first-line Opioid Addiction Treatment (OAT) option, along with buprenorphine. Methadone may be preferable to buprenorphine for patients who are at high risk of treatment cessation and subsequent fentanyl overdose. It also alters processes affecting analgesia, emotional responses to pain, and reduces withdrawal symptoms from other opioid drugs

Mechanism of action

Methadone hydrochloride is a mu-agonist, which is a synthetic opioid analgesic with multiple actions that are similar to those of morphine (7). The most prominent actions impact the central nervous system and organs composed of smooth muscle.

Methadone binds to opiate receptors in the CNS, causing inhibition of ascending pain pathways and altering the perception of and response to pain (12). It also produces generalized CNS depression (12). Methadone has also been shown to have N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonism. The contribution of NMDA receptor antagonism to methadone’s efficacy is unknown.

Methadone binds to plasma proteins in circulation, most predominantly α1-acid glycoprotein (9). This is an important consideration as certain conditions or medications may alter plasma protein levels. There is considerable tissue distribution of methadone, and it is possible for tissue levels to exceed plasma levels.

The lipophilic nature of methadone allows for rapid absorption, long duration of action, and slow release from tissues into the bloodstream. This accounts for the wide variation in half-life, recorded as a range from two to 65 hours.

Methadone is metabolized into inactive molecules by the liver CYP450 enzyme and the intestinal CYP3A4/CYP2D6 enzymes before elimination in the feces or urine.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you name the uses of methadone?

- How does the mechanism of action of methadone help to alleviate withdrawal symptoms from opioids?

- Is the half-life of this drug considered long or short?

- Why is it important to recognize that methadone binds to plasma proteins in circulation?

Methadone Pharmacokinetics

Figure 3. Pharmacokinetics of Methadone (12)

- Well absorbed after IM injection.

- Protein binding: 85%–90%.

- Metabolized in liver. Primarily excreted in urine.

- Not removed by hemodialysis.

- Half-life: 7– 59 hrs.

- Crosses placenta and found in breast milk.

Respiratory issues may occur in neonates if mother received opiates during labor.

Elderly patients are more susceptible to respiratory depressant effects.

Age-related renal impairment may increase the risk of urinary retention.

Caution: Renal/ hepatic impairment, elderly/debilitated patients, risk for QT prolongation, medications that prolong QT interval, conduction abnormalities, severe volume depletion, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, cardiovascular disease, depression, suicidal tendencies, history of drug abuse, respiratory disease, and biliary tract dysfunction.

Drug Interactions

Alcohol, other CNS depressants (e.g., Lorazepam, morphine, zolpidem) may increase CNS effects, respiratory depression, and hypotension.

CYP3A4 inducers (e.g., carbamazepine, phenobarbital) may decrease concentration/effects; CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., rifampin, clarithromycin) (12).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you name drugs that should be carefully monitored when prescribed along with methadone?

- What are examples of additional precautions for elderly patients?

Methadone Side Effects

As with other opioid medications, general side effects of methadone are related to excessive opioid receptor activity, including but not limited to:

- Diaphoresis/flushing

- Pruritis

- Nausea

- Dry mouth

- Constipation

- Sedation

- Lethargy

- Respiratory depression

Adverse Effects

Cardiovascular: Bigeminy, bradycardia, cardiac arrhythmia, cardiac failure, cardiomyopathy, ECG changes, edema, extrasystoles, flushing, hypotension, inversion T wave on ECG, palpitations, phlebitis, prolonged QT interval on ECG, shock, syncope, tachycardia, torsades de pointes, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia

Central nervous system: Agitation, confusion, disorientation, dizziness, drug dependence (physical dependence), dysphoria, euphoria, hallucination, headache, insomnia, sedation, seizure

Dermatologic: Diaphoresis, hemorrhagic urticaria (rare), pruritus, skin rash, urticaria

Endocrine & metabolic: Adrenocortical insufficiency, altered hormone level (androgen deficiency; chronic opioid use), amenorrhea, antidiuretic effect, decreased libido, decreased plasma testosterone, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, weight gain

Gastrointestinal: Abdominal pain, anorexia, biliary tract spasm, constipation, glossitis, nausea, vomiting, xerostomia

Genitourinary: Asthenospermia, decreased ejaculate volume, male genital disease (reduced seminal vesicle secretions), prostatic disease (reduced prostate secretions), spermatozoa disorder (morphologic abnormalities), urinary hesitancy, urinary retention

Hematologic: Thrombocytopenia (reversible, reported in patients with chronic hepatitis)

Neuromuscular & skeletal: Amyotrophy, bone fracture, osteoporosis, weakness

Ophthalmic: Visual disturbance

Respiratory: Pulmonary edema, respiratory depression

Warnings

- May prolong QT interval, which may cause serious arrhythmias.

- May cause serious, life-threatening, or fatal respiratory depression.

- Monitor for signs of misuse, abuse, addiction.

- Prolonged maternal use may cause neonatal withdrawal syndrome.

Do not confuse methadone with Mephyton, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, methylphenidate, or morphine

Serious adverse effects: pancreatitis, hypothyroidism, Addison’s disease, head injury, increased intracranial pressure.

Methadone Dosing and Titration for APRNs

The following are tips for nurse clinicians in dosing and titrating Methadone (3):

- The clinician should attempt to reach an optimal dose of methadone safely and quickly (3).

- Starting methadone at 30mg is recommended.

- The starting dose of methadone can be increased by 10–15mg every three to five days.

- Slower titration is recommended for patients at higher risk of toxicity (e.g., older age, sedating medications or alcohol, patients new to methadone).

- Patients who have recently been on methadone dosing at higher doses (i.e., in the previous week) can be considered for more rapid dose increases based on their tolerance.

- Once a dose of 75–80mg is reached, the dose can then be increased by 10mg every five to seven days.

- If four consecutive missed doses, the dose of methadone should be reduced by 50% or to 30mg, whichever is higher. If five or more consecutive doses are missed, methadone should be restarted at a maximum of 30mg and titrated according to patient need.

- Sustained-release oral morphine (SROM), at a maximum starting dose of 200mg, can be added on the day of a restart as long as the patient has not become completely opioid-abstinent.

- For patients who use fentanyl regularly, methadone doses of 100mg or higher are often appropriate.

- Use prescription practices that promote treatment retention, including phone visits, check-ins, extending prescriptions, or leaving longer duration methadone prescriptions for 30mg at the pharmacy so patients can restart treatment.

- Be aware of the limitations of urine drug testing.

- Provide treatment for concurrent psychiatric illnesses and substance use disorders.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you explain the major side effects and adverse effects of methadone?

- Can you describe the recommendations on missed doses of methadone?

- What is the recommended starting dose of this drug?

- What are some ways to manage gastrointestinal effects of the drug?

Pregnancy and Methadone

Opioid withdrawal is associated with a high risk for spontaneous abortion and preterm labor, so pregnant patients with OUD should be started as soon as possible and titrated to avoid withdrawal symptoms (3). Hospital admission for rapid up-titration of methadone with augmenting opioids is recommended if possible. When caring for a pregnant patient using fentanyl, it is vital to contact an obstetrical team early. Use of opiates during pregnancy produces withdrawal symptoms in neonate, including irritability, excessive crying, tremors, hyperactive reflexes, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, yawning, sneezing, seizures (12).

Guidance for Kentucky APRNs

Prescribing Opioids

Before prescribing opioids, complete a detailed patient history and assessment that includes:

- Indication of pain relief request

- Location, nature, and intensity of pain

- Prior pain treatments and response

- Diagnostic testing

- Comorbid conditions

- Potential physical and psychologic pain impact on function

- Family support, employment, and housing

- Leisure activities, mood, sleep, and substance use

- Signs of emotional, physical, or sexual abuse

When considering opioids, weigh the benefits with the risks of abuse or addiction, adverse drug reactions, overdose, and physical dependence.

Assessment Tools

Screening tools can assist in determining risk level and the degree of monitoring and structuring required for a treatment plan. Examples include:

- Brief Intervention Tool

- 26-item “yes-no” questionnaire used to identify signs of opioid addiction or abuse.

- Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM)

- The Current Opioid Misuse Measure is a 17-item patient self-report assessment.

- Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk, and Efficacy (DIRE) Tool

- The Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk, and Efficacy is a clinician-rated questionnaire used to predict patient compliance with long-term opioid therapy.

- Opioid Risk Tool

- The Opioid Risk Tool is a five-item assessment to evaluate for aberrant drug-related behavior.

- Pain Assessment and Documentation Tool (PADT)

- The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Federation of State Medical Boards, and Joint Commission stress documentation from both a quality and diagnostic perspective.

- Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R)

- The Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R) is a screening with questions addressing the history of alcohol or substance use, cravings, mood/psychological status, and stress.

- Urine Drug Tests (UDT)

- The CDC recommends drug testing before starting opioid therapy and routinely to detect unanticipated drug use.

Checklists For Prescribers and Dispensers

- Dose, frequency, and length prescribed consistent with the indication – avoid long-acting opioids for acute pain

- Age, weight, height, and sex considered

- Evaluate for potential drug interactions

- Evaluate for potential allergic reactions

- Patient informed and verbalized understanding of the risks and benefits

- Warnings about addiction, abruptly halting, use of power equipment, side-effects, respiratory depression, avoid sharing or using not as prescribed.

- Medication use agreement in place.

- Instructions for storage and disposal of unused opioids.

Potential Signs of Drug Misuse

The following are red flags of misuse:

- Only drugs prescribed are controlled substances

- Early refills

- Pays cash, although insurance is present.

- Lost prescriptions

- Remote address

- Multiple prescribers

- Concerning PDMP or KASPAR (Kentucky All Schedule Prescription Reporting) results

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you name a few tools available to clinicals when addiction disorders are suspected?

- How can these assessment tools be integrated into screening at primary care clinics?

Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs)

Kentucky has mandatory PDMP Use Laws for clinicians who prescribe certain medications. APRNs are required to use and apply the information gained from this database into practice.

Prescription drug monitor programs (PDMPs) are in place in various methods and degrees in all states. These databases assist prescribers and dispensers in working together to decrease drug misuse.

The key benefits include (6):

- Assists in monitoring opioid prescriptions.

- Identify if multiple providers are providing prescriptions for the same individual (avoids “doctor shopping”).

- Assists regulatory boards, Medicaid, medical examiners, law enforcement, and research organizations in gathering data on the effectiveness and enforcement of regulations.

- PMP Interconnect allows the sharing of prescription information across state lines.

KASPAR (Kentucky All Schedule Prescription Reporting)

KASPER is a controlled substance prescription monitoring system designed to assist practitioners and pharmacists. KASPER also provides an investigative tool for law enforcement and regulatory agencies to assist with authorized reviews and investigations. The report shows all Schedule II through V controlled substance prescriptions a patient has received and a list of prescribers who prescribed them (6).

Practitioners can request this report to review data on controlled substances administered or dispensed to their patient prior to prescribing. This is also a tool to assess the prescriptions obtained by a birth mother of an infant being treated for neonatal abstinence syndrome or prenatal drug exposure.

To obtain the report, go to the Kentucky Online Gateway website or call KOG Help Desk at 502-564-0104)

Requirements for an initial prescribing of a controlled substance for pain or associated with the same primary complaint (201 KAR 9:260 Section 3): (6)

- Appropriate medical history and physical exam.

- Obtain KASPER report for the previous 12-month period.

- Do not prescribe or dispense long-acting or controlled-release controlled substances for acute pain not associated with recent surgery.

- Explain that the medication is intended to treat acute pain for a time-limited use, and to discontinue when resolved.

- If Schedule II Controlled Substance or Schedule III Controlled Substances with hydrocodone:

- Make a written plan stating the objectives of the treatment and further diagnostic examinations required

- Discuss the risks and benefits of controlled substance use.

- Obtain written consent for treatment

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you name specific laws and regulations for prescribers in Kentucky?

- How can KASPER reports be obtained?

- What are some benefits of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs)?

- What schedule of controlled substance prescriptions are included in the KASPER report?

Conclusion

When designing a treatment strategy to battle this addiction and abuse crisis, it is important to look at common addiction disorders, the pharmacokinetics of opioids, prescribing guidance and laws, and pharmacological interventions that clinicians can use to help improve this crisis. Kentucky is facing poor outcomes in the battle against opioid use disorders (OUD), but with broader research and education, healthcare policy initiatives, and support of those impacted, there is significant hope!

KENTUCKY PHARMACOLOGY AND ADDICTION DISORDERS

Introduction

Individuals struggling with an addiction often feel powerless and hopeless in the battle. Thankfully, there are effective tools to empower and provide hope to these individuals, including initiatives for support, medications, counseling, behavioral therapies, as well as regulations to prevent inappropriate prescribing.

This course will provide pharmacology of opioids and drugs that can be an effective treatment tool, including buprenorphine and naltrexone. It is meaningful to explore the etiology of addiction disorders impacting the state of Kentucky and review laws and prescribing regulations.

Understanding Kentucky Addiction Disorders

The United States is facing an opioid crisis. The number of overdose deaths involving opioids, including prescription opioids, heroin, and synthetic opioids (like fentanyl), is currently roughly 10 times the number in 1999 (2). Opioid overdoses took the lives of 80,000 people in 2021 in the U.S., and nearly 88% of those deaths involved synthetic opioids (2).

Kentucky ranks in the top 10 states for drug overdoses in the U.S. (5). In 2022, there were 2,135 overdose deaths in Kentucky approximately 90% of those deaths involved opioids (5). Fentanyl causes more overdose fatalities than any other type of drug and in Kentucky, fentanyl was present in 70% of overdose deaths last year (5).

In 2021, a total of 12,946 Kentucky residents visited an ED for a nonfatal drug overdose (5).

Legislators in Kentucky have recognized the devastation of addiction disorders and created many initiates to prevent, identify, and treat addiction disorders, specifically opioid use disorders.

Opioid-Related Laws and Prescribing Regulations for APRNs in Kentucky

Several laws and policies are in place to mitigate the impact of increased opioid addiction and deaths. These include regulations for prescribers, legislation permitting the operation of syringe exchange programs, and Good Samaritan laws that provide legal protections to bystanders who seek help in the event of an overdose.

APRNs should be aware of the state laws, regulations, guidance, and policies related to oversight of opioid prescribing and monitoring of opioid use.

Kentucky’s Controlled Substances Act governs all controlled substances and has many provisions to be aware of (8).

- Kentucky’s Senate Bill 192, enacted in 2015, provided substance abuse treatment funds and amended KRS 218A.500 to permit communities to set up syringe exchange programs (8).

- Kentucky’s Good Samaritan Law (KRS 218A.133) protects individuals from prosecution if they seek medical attention while experiencing a drug overdose in certain circumstances (8). It also protects individuals from prosecution when they report a drug overdose if they stay with the individual who has overdosed until first responders arrive.

- Kentucky Administrative Regulations (KAR) KRS 218A.172 addresses prescribing and dispensing Schedule II controlled substances and Schedule III controlled substances containing hydrocodone.

- It requires prescribers to obtain the patient’s medical history and conduct a physical or mental health examination, obtain patient data in the prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP), make a written plan of treatment, discuss the risks with the patient, obtain written consent for treatment, and review data and modify treatment when needed (8).

- KRS 218A:205, limits the prescribing of a Schedule II controlled substance used for acute pain to a 3-day supply (8).

- Kentucky’s prescription drug monitoring program, Kentucky All Schedule Prescription Electronic Reporting (KASPER KRS 218A.172) requires prescribers to check KASPER.

- Required prior to the initial prescribing or dispensing of any Schedule II or Schedule III controlled substance containing hydrocodone

- Every three months thereafter

- Prescribers are required to complete continuing education relating to the use of KASPER, pain management, addiction disorders, or a combination of two or more of these subjects (KRS 218A.205).

The exceptions for an APRN to prescribe greater than a 3-day supply of hydrocodone combination products include only the following (4).

- In the professional judgment of the APRN, more than a 3-day supply is needed. The need must be thoroughly documented.

- Treating chronic pain.

- Treating cancer pain.

- Treating a patient at end of life or in Hospice.

- Treatment of pain after major surgery or significant trauma as defined by the licensing Board and the Office of Drug Control Policy.

- Administered directly to the patient in an inpatient setting.

- Scenarios authorized by the licensing board.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you describe the Good Samaritan law in Kentucky?

- How can the availability of syringe exchange programs impact communicable diseases?

- What are restrictions on opioid prescribing in Kentucky?

- What is the limit (in days) for supply of Schedule II and Schedule III controlled substance containing hydrocodone when prescribed for acute pain in Kentucky?

Basic Pharmacology of Opioids

Opioids are a group of analgesic agents commonly used in clinical practice. Opioid receptors are G-protein-coupled receptors which cause cellular hyperpolarization when bound to opioid agonists (3).

As long ago as 3000 BC the opium poppy, Papaver somniferum, was cultivated; followed by morphine being isolated from opium in 1806 by Serturner (3).

Opioids can also be classified according to their effect on opioid receptors and can be considered as agonists, partial agonists, antagonists, and agonist-antagonists (3).

- Agonists – interact with an opioid receptor to produce a maximal response from that receptor.

- Antagonists – bind to receptors but produce no functional response, while at the same time preventing an agonist from binding to that receptor (naloxone).

- Partial agonists – bind to receptors but elicit only a partial functional response regardless of the amount of drug administered

- Agonist-antagonists – act as agonist to a certain opioid receptor, but have antagonist activity to another opioid receptor

Naturally occurring opioid receptors are present throughout the body, both centrally (e.g., in the brain and spinal cord) and peripherally (e.g., in the heart and gut). The primary opioid receptors that have been identified are the mu (μ), kappa (κ), and delta (δ) subtypes (1). All of the opioid receptor subtypes are seven-transmembrane G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) that can exist in both active and inactive states.

Opioid agonists bind to inhibitory G proteins, which ultimately activate various signaling cascades. When opioid receptors are activated, release of the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is decreased (1). GABA produces a tonic inhibition of dopamine release, so this inhibition of GABA causes an increase in dopamine release. In the past few years, several important advances have occurred in our understanding of opioid receptor functioning, including biased signaling, allosteric regulation, and heteromerization (1).

Pain can be categorized as nociceptive, neuropathic or nociplastic pain (a combination of both that cannot be entirely explained as nociceptive or neuropathic). Nociceptive pain is generated as a warning signal transmitted to the brain about the possible damage of a non-neural tissue (9).

Neuropathic pain typically results from damage to neural tissue caused by a disease, toxin, or infection. The next type, called nociplastic pain, is a chronic and complex pain, not completely defined but probably caused by an alteration of neurons’ pain response and an increased sensitivity of the central nervous system (CNS). This pain sensations and is commonly observed in patients with cancer and other long-term chronic disorders (9).

The opioid system is a physiological control system that facilitates communication among a significant number of endogenous opioid peptides and several types of opioid receptors in the CNS and peripheral nervous system.

This system also significantly modulates numerous sensory, emotional, cognitive functions, as well as addictive behaviors (9). It is also involved in other physiological functions, including responses to stress, respiration, gastrointestinal transit, endocrine, and immune functions (9).

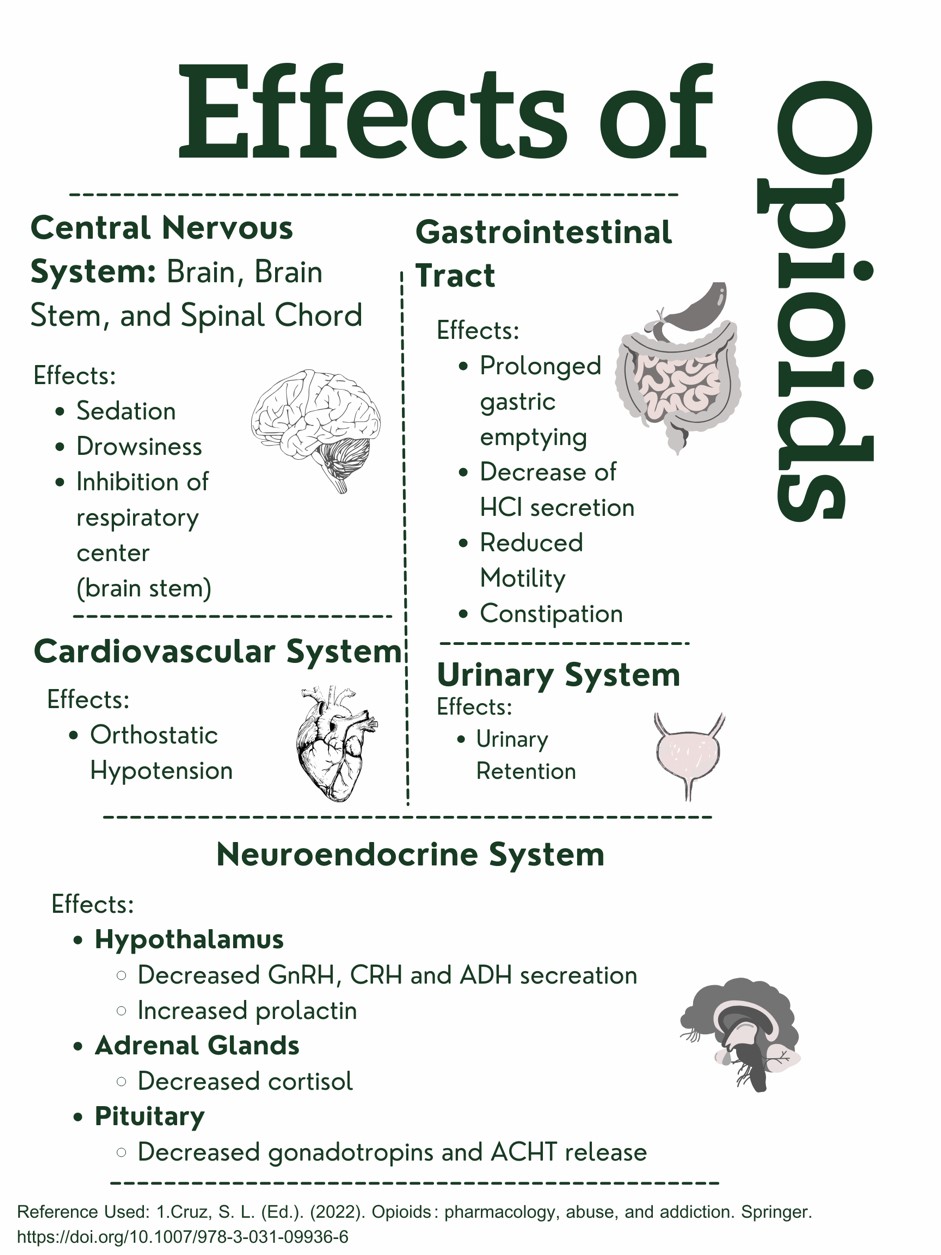

Figure 1. Effects of Opioids on the Body. Designed by Author. Information retrieved from (15).

Figure 1. Effects of Opioids on the Body. Designed by Author. Information retrieved from (15).

This design was created and copyrighted by Abbie Schmitt, RN, MSN and may not be reproduced without permission from Nursing CE Central.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you name the physiological effects of opioids on the different systems of the body?

- How are the actions of agonists and antagonists different in their interaction with opioid receptors?

- How does the activation and cascade of opioid receptors impact GABA and dopamine?

- Can you discuss the different categories of pain?

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD)

An opioid use disorder (OUD) is defined as a problematic pattern of opioid use that leads to serious impairment or distress (1). Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is the use of medications, in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies, in the treatment of opioid use disorders (OUD). The goal is sustained recovery.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has only approved three medication assisted treatments (MATs) for opioid use disorder (OUD): buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone.

FDA-approved buprenorphine products approved for the treatment of OUD include:

- Brixadi (buprenorphine) injection for subcutaneous use

- Bunavail (buprenorphine and naloxone) buccal film

- Cassipa (buprenorphine and naloxone) sublingual film

- Probuphine (buprenorphine) implant for subdermal administration

- Sublocade (buprenorphine extended release) injection for subcutaneous use

- Suboxone (buprenorphine and naloxone) sublingual film for sublingual or buccal use, or sublingual tablet.

- Subutex (buprenorphine) sublingual tablet

- Zubsolv (buprenorphine and naloxone) sublingual tablets

FDA-approved methadone products for the treatment of OUD include:

- Dolophine (methadone hydrochloride) tablets

- Methadose (methadone hydrochloride) oral concentrate

FDA-approved naltrexone products for the treatment of OUD include:

- Vivitrol (naltrexone for extended-release injectable suspension) intramuscular

The FDA requires that prescribing information for medicines that are intended for use in the outpatient setting include how to safely decrease the dose. Prescribers should not abruptly discontinue opioids in a patient who is physically dependent, but slowly decrease the dose of the opioid and continue to manage pain therapeutically.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Are medications intended to be used independently of other therapeutic measures in the treatment of OUD?

- Can you discuss the medications that are approved by the FDA for the treatment of OUD?

- Is it appropriate to abruptly quit these medications?

- Have you had experience administering methadone or similar drugs?

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine should be used as part of a comprehensive treatment program to include counseling and psychosocial support.

Definition

Buprenorphine is a synthetic opioid developed in the late 1960s and is used to treat opioid use disorder. This drug is a synthetic analog of thebaine, which is an alkaloid compound derived from the poppy flower (6).

Buprenorphine is categorized as a Schedule III drug. This schedule includes drugs that have a moderate-to-low potential for physical dependence or a high potential for psychological dependence (6).

Buprenorphine is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat acute and chronic pain and opioid use disorder.

Drug Class

- Analgesic, Opioid

- Analgesic, Opioid Partial Agonist

Uses

Buprenorphine is used to treat opioid use disorder (OUD) and to manage pain that is severe enough to require long-term opioid treatment, and in patients for which alternative treatment options (e.g., nonopioid analgesics) are ineffective, not tolerated, or inadequate enough to provide sufficient management of pain (13).

Buprenorphine should be used as part of a complete treatment program to include counseling and psychosocial support.

Mechanism of Action

Buprenorphine has an analgesic effect by binding to mu opiate receptors in the CNS. Due to it being a partial mu agonist, its analgesic effects plateau at higher doses and it then behaves like an antagonist (13). This is a meaningful attribute, and this plateauing of its analgesic effects at higher doses, causes it to have ceiling, or limited, effects on respiratory depression (6). This is a positive attribute, signifying its safety superiority.

Buprenorphine exhibits high-affinity binding to the mu-opioid receptors and slow-dissociation kinetics. In this way, it differs from other full-opioid agonists such as morphine and fentanyl, which results in milder and less uncomfortable withdrawal symptoms for the patient (6).

Essentially, the benefits of this drug include: (1) higher doses do not lead to greater analgesic effects, thus respiratory depression; and (2) the withdrawal symptoms from buprenorphine are not as intense as full-opioid antagonists.

The extended-release formulation is injected subcutaneously as a liquid (13).

Note on absorption: When administered orally, buprenorphine has poor bioavailability due to the first-pass effect, in which the liver and intestine metabolize the drug.

The preferred route of administration is sublingual, so it can have rapid absorption and circumvent the first-pass effect. Placing the tablet under the tongue results in a slow onset of action, with the peak effect occurring approximately 3 to 4 hours after administration (6).

Pharmacodynamics/Kinetics

Pharmacodynamics/Kinetics of buprenorphine include the following (13).

- Onset of action: Immediate-release IM: ≥15 minutes

- Peak effect: Immediate-release IM: ~1 hour

- Duration: Immediate-release IM: ≥ 6 hours; Extended-release Sub-Q: 28 days

- Absorption: Immediate-release IM and Sub-Q: 30% to 40%.

- Application of a heating pad may increase blood concentrations of buprenorphine 26% to 55%.

- Distribution: Cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) concentrations are 15% to 25% of plasma concentrations

- Protein binding: High (~96%, primarily to alpha- and beta globulin)

- Metabolism: Primarily hepatic via N-dealkylation by CYP3A4 to norbuprenorphine (active metabolite), and to a lesser extent via glucuronidation by UGT1A1 and 2B7 to buprenorphine 3-O-glucuronide; the major metabolite, norbuprenorphine, also undergoes glucuronidation via UGT1A3; extensive first-pass effect

- Bioavailability (relative to IV administration): Buccal film: 46% to 65%; Immediate-release IM: 70%; Sublingual tablet: 29%; Transdermal patch: ~15%

- Half-life elimination in adults:

- IV: 2.2 to 3 hours

- Buccal film: 27.6 ± 11.2 hours

- Sublingual tablet: ~37 hours

- Transdermal patch: ~26 hours

- Time to peak, plasma:

- Buccal film: 2.5 to 3 hours

- Extended-release Sub-Q: 24 hours, with steady state achieved after 4 to 6 months

- Subdermal implant: 12 hours after insertion, with steady state achieved by week four

- Sublingual: 30 minutes to 1 hour

- Transdermal patch: Steady state achieved by day three

- Excretion: Most of the drug and its metabolite are eliminated through feces, with less than 20% excreted by the kidneys (6)

- Clearance: Related to hepatic blood flow

- Adults: 0.78 to 1.32 L/hour/kg

Adverse Effects

Buprenorphine has anticholinergic-like effects and may cause CNS depression, dry mouth, dizziness, hypotension, drowsiness, QT prolongation, and lower seizure threshold (6).

Additional adverse effects of buprenorphine include:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Headache

- Memory loss

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Urinary retention

Following buprenorphine treatment, a patient’s tolerance to opioids decreases, increasing risk for harm if they resume their previous opioid dosage. Patients should be strongly advised against using opioids without prior consultation with their healthcare provider.

Warnings

Prescribers should exercise caution when prescribing buprenorphine to patients with hepatic impairment, morbid obesity, thyroid dysfunction, a history of ileus or bowel obstruction, prostatic hyperplasia or urinary stricture, CNS depression or coma, delirium tremens, depression, anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and toxic psychosis (6).

Concerns related to adverse effects:

Hepatic Impairment

- In individuals with hepatic impairment, such as patients with hepatitis B and C, the dose of buprenorphine has to be modified to prevent toxicity (6). As buprenorphine metabolism takes place in the liver, individuals with liver impairment should undergo close monitoring of their liver function and drug levels. Clinicians should educate patients with hepatitis about the correlation between IV use of buprenorphine and hepatotoxicity (6).

- For buccal film and sublingual tablets in patients with severe hepatic impairment, it is advisable to reduce the dose by 50% and closely monitor for signs and symptoms of toxicity.

- Subcutaneous injections are not recommended.

CNS Depression

- Due to side effects and CNS depression, patients must be cautioned about performing tasks that require mental alertness (e.g., operating machinery, driving).

Hypersensitivity Reactions

- Hypersensitivity, including bronchospasm, angioneurotic edema, and anaphylactic shock, have been reported. The most common symptoms include rash, hives, and pruritus.

Hypotension

- Clinicians must be aware of possible hypotension (including orthostatic hypotension and syncope); use with caution in patients with hypovolemia, cardiovascular disease, or if patient takes drugs that may exaggerate hypotensive effects (including phenothiazines or general anesthetics).

- Monitor for symptoms of hypotension following initiation or dose titration.

Infection from Subdermal Implant

- Infection may occur at the site of insertion or removal (6).

Figure 2. Buprenorphine Injectable (13)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Can you describe the mechanisms of action for Buprenorphine?

- What are some comorbidities to be careful with when prescribing this drug?

- How are the mechanisms of actions for Buprenorphine different than the mechanisms of actions for opioids?

- Can you describe the analgesic effects of higher doses of Buprenorphine?

Naltrexone

Naltrexone is a pure opioid antagonist, it acts as a competitive antagonist at opioid receptor sites, showing the highest affinity for mu receptors (14).

Naltrexone was developed in 1963 and patented in 1967 and is used for treatment of alcohol use disorders (6). In 1984, naltrexone received approval for medical use in the U.S.

Drug Class

- Antidote

- Opioid Antagonist

Uses

- Alcohol use disorder: FDA-approved

- Opioid use disorder: For the blockade of the effects of exogenously administered opioids; FDA-approved

- A fixed-dose combination of naltrexone and bupropion is FDA-approved for obesity (6)

- Researchers are studying its use in patients with stimulant use disorder, particularly patients with polydrug dependence on opioids, heroin, and amphetamine (6)

Mechanism of Action

Naltrexone (and its active metabolite 6-beta-naltrexone) is pharmacologically effective against opioids by blocking the mu-opioid receptor.

Naltrexone blocks the effect of opioids and prevents opioid intoxication and physiologic dependence on opioid users. Naltrexone helps with alcohol dependency because it modifies the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to suppress ethanol consumption (14) .

Opioids act mainly via the mu receptor, although they affect mu, delta, and kappa-opioid receptors. Naltrexone competes for opiate receptors and displaces opioid drugs from these receptors, thus reversing their effects (14). It is capable of antagonizing all opiate receptors. (14). Exogenous opioids include the commonly prescribed pain relievers such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, and heroin. These typically induce euphoria at much higher doses than those prescribed by medical providers to relieve pain. If naltrexone occupies the receptors, the opioids are not going to provide these euphoric effects.

According to guidelines by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), a combination of buprenorphine and low doses of oral naltrexone is effective for opioid use disorder for managing withdrawal (14).

Pharmacodynamics/Kinetics

- Duration: Oral: 50 mg: 24 hours; 100 mg: 48 hours; 150 mg: 72 hours; IM: 4 weeks

- Absorption: Oral: Almost complete

- Distribution: Vd: ~1350 L; widely throughout the body but considerable interindividual variation exists

- Metabolism: Extensively metabolized via noncytochrome-mediated dehydrogenase conversion to 6-beta-naltrexol (primary metabolite) and related minor metabolites; glucuronide conjugates are also formed from naltrexone and its metabolites

- Oral: Extensive first-pass effect

- Protein binding: 21%

- Bioavailability: Oral: Variable range (5% to 40%)

- Half-life elimination:

- Oral: 4 hours; 6-beta-naltrexol: 13 hours

- IM: naltrexone and 6-beta-naltrexol: 5 to 10 days (dependent upon erosion of polymer)

- Time to peak, serum:

- Oral: ~60 minutes

- IM: Biphasic: ~2 hours (first peak), ~2 to 3 days (second peak)

- Excretion: Primarily urine (as metabolites and small amounts of unchanged drug)

Side Effects

Commonly reported side effects of naltrexone include:

- Abdominal pain

- Gastrointestinal Distress

- Constipation

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Insomnia

- Joint and muscle pain

- Fatigue

- Loss of strength and energy

- Tooth pain

- Dry mouth

- Increased thirst

Warnings

Patients should be opioid-free for a minimum of 7 to 10 days prior to taking naltrexone (14)

Prescribers must be aware that patients who had been treated with naltrexone may respond to lower opioid doses than previously used, which could result in potentially life-threatening or fatal opioid intoxication. Patients should be educated that they may be more sensitive to lower doses of opioids after naltrexone treatment is discontinued, after a missed dose, or near the end of the dosing interval (14).

Opioid withdrawal may be noted in patients, and symptoms include pain, hypertension, sweating, agitation, and irritability; in neonates: shrill cry, failure to feed (14).

Cases of eosinophilic pneumonia have been reported and should be assessed in patients presenting with progressive hypoxia and dyspnea.

Hepatotoxicity can occur, and clinicians should note that elevated transaminases may be a result of alcoholic liver disease, hepatitis B and/or C infection, or concomitant use of other hepatotoxic drugs; abrupt opioid withdrawal may also lead to acute liver injury. Clinicians should discontinue this drug if any signs or symptoms of hepatotoxicity are found.

Drug-Drug Interactions:

- Bremelanotide- Contraindicated to administer with naltrexone due to reduced therapeutic effect of naltrexone (10).

- Thioridazine – Contraindicated to administer with naltrexone due to the risk of lethargy and somnolence (10).

- Methylnaltrexone: May enhance the adverse/toxic effect of opioid antagonists; the risk for opioid withdrawal may be increased (14).

- Naldemedine: Opioid Antagonists may enhance the adverse/toxic effect of naldemedine; the risk for opioid withdrawal may be increased (14).

Treatment Resources

The KY HELP Call Center is available to those with a substance use disorder, or their friends or family members, as a resource for information on treatment options and treatment providers.

Individuals may call 833-8KY-HELP (833-859-4357) to speak one-on-one with a specialist who will connect them with treatment as quickly as possible (5).

The Kentucky Injury Prevention and Research Center (KIPRC) at the University of Kentucky College of Public Health manages a vital website, www.findhelpnowky.org, for Kentucky health care providers, court officials, families and individuals seeking options for substance abuse treatment and recovery (5).

The Kentucky State Police (KSP) Angel Initiative is a proactive program designed to help those who battle addiction. There are 16 posts located throughout the commonwealth that will connect individuals with a local officer who will assist with locating an appropriate treatment program. The Angel Initiative is completely voluntary, and individuals will not be arrested or charged with any violations if they agree to participate in treatment.

Figure 3. Substance Use Disorder Call Center Contact Information (5)

Conclusion

A common theme among individuals who struggle with OUD is a loss of power to this addictive substance. There is significant opportunity to help this population gain back control, including legislation and supportive initiative, and appropriate combined use of medications, counseling, and behavioral therapies. Knowledge on the pharmacology of opioids, as well as buprenorphine and naltrexone is critical. Although the opioid crisis is substantial, there is hope on the horizon.

SSRI Use in Major Depressive Disorder

Introduction

When hearing the phrase selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, what comes to mind? If you’re an advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) with prescriptive authority, you’ve heard of SSRIs before. Even as a nurse or maybe before nursing school, conversations about prescription drug use and mental health existed every so often.

Presently, patients seek guidance and information on various health topics from APRNs, including medication management, women’s health, and mental health. The information in this course will serve as a valuable resource for APRNs with prescriptive authority of all specialties, education levels, and backgrounds to learn more about SSRIs and major depressive disorder (MDD).

Defining SSRIs

What Are SSRIs?

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, known as SSRIs, are a type of pharmacological drug class. SSRIs have existed for the past several decades as a class of prescription medications that can manage major depressive disorder (MDD) and other mental health conditions (1).

While this course focuses explicitly on SSRI use in MDD management, SSRIs are also Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved to manage obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder (PD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and social anxiety disorder (SAD). In addition, several off-label uses for SSRI include management for binge eating disorder and menopausal vasomotor symptoms.

How and Where Are SSRIs Used?

SSRIs are commonly prescribed to manage MDD and other mood disorders in the U.S. and around the world in pediatric, adult, and geriatric populations (1, 2). SSRIs can be taken by mouth as a pill, capsule, or liquid oral solution. Presently, SSRIs cannot be offered via intravenous, rectal, buccal, or injection routes.

What Is the Clinical Criteria for Prescribing SSRIs?

Clinical criteria for prescribing SSRIs can vary depending on the intention for the SSRI. In the case of MDD, several factors can play a role in the clinical criteria for prescribing SSRIs. A patient’s adherence to swallowing a pill daily, dosage given the patient’s weight, medical history, and MDD concerns, and prior experience with other medications can influence prescribing SSRIs. When considering prescribing SSRIs for MDD management, consider assessing the patient for MDD first, taking a detailed health history, and discussing the risk versus benefits of starting SSRIs for this patient (1, 3).

What Is the Average Cost for SSRIs?

Cost for SSRIs can significantly vary depending on the type of SSRI, insurance, dosage, frequency, and other factors. Cost is among leading reasons why many patients cannot maintain their medication regime (4). If cost is a concern for your patient, consider reaching out to your local pharmacies or patient care teams to find cost-effective solutions for your patients.

What Is Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)?

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a mental health condition in which a person has consistent appetite changes, sleep changes, psychomotor changes, decreased interest in activities, negative thoughts, suicidal thoughts, and depressed mood that interfere with a person’s quality of life (5). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, a patient must have at least five persistent mood related symptoms, including depression or anhedonia (loss of interest in activities once enjoyed), that interferes with a person’s quality of life to be formally diagnosed with MDD. Note that MDD does not include a history of manic episodes, and pediatric populations can present with more variable MDD symptoms (5). As an APRN, you can assess for MDD by doing a detailed patient health history or having a patient complete the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) – a depression assessment tool (5).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some medication administration options for SSRIs?

- What populations can be prescribed SSRIs?

SSRI Pharmacokinetics

Drug Class SSRIs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, known as SSRIs, are a type of pharmacological drug class part of the antidepressant drug class. They can be prescribed at various dosages depending on the patient history, severity of major depressive disorder (MDD), other medication use, and other factors based on patient-centered decision making. Currently, SSRIs that are FDA approved for MDD management include paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, vilazodone, and fluoxetine. SSRIs can be prescribed for the oral route and are available via capsule, tablet, or liquid suspension/solution. SSRIs can be taken at any time of day. They can be taken with or without food, though vilazodone in particular is recommended with food. SSRIs are often prescribed to be taken once a day, sometimes twice a day, depending on the severity of MDD. Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy (1).

SSRIs are metabolized by and known to affect the cytochrome P450 system. CYP2D6 inhibitors include escitalopram, citalopram, sertraline, paroxetine, and fluoxetine. Fluoxetine and fluvoxamine are inhibitors of CYP2C19. Fluvoxamine is an inhibitor of CYP1A2. Consider reviewing a patient’s medication history and health history prior to prescribing SSRIs (1).

SSRIs Method of Action

SSRI method of action has been subject to several studies, especially in the last few years. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that plays a role in mood and other bodily functions. It can be measured in plasma, blood, urine, and CSF (6). It is important to note that serotonin is rapidly metabolized to 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) (6). SSRIs work by inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin at certain chemical receptors, thereby increasing serotonin activity and concentration (1). SSRIs inhibit the serotonin transporter (SERT) at the presynaptic axon terminal.

By obstructing the SERT, a higher amount of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5HT) remains in synaptic clefts. This higher amount of serotonin can then stimulate postsynaptic receptors for a more extended period (1). While SSRIs can increase serotonin activity, there is some evidence that suggests the possibility of long-term SSRI use reducing serotonin concentration (6). In addition, the clinical response to SSRIs in patients with MDD can take anywhere from a few to several weeks to emerge (7). While some research suggests that there are initial improvements in mood, evidence remains inconclusive as to the exact time SSRIs can take to provide a therapeutic response for patients (7). Also, while research suggests that SSRIs can increase serotonin levels, there is still mixed evidence on the exact method of action for SSRIs (7).

As a result, it is important to counsel patients that SSRIs can take a few weeks to provide a therapeutic response and to monitor mood and symptoms while taking SSRIs.

SSRI Side Effects

Every medication has the possibility of side effects, and SSRIs are no exception. Fortunately, SSRIs are known to have less side effects than other drug classes of antidepressants, such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). The most commonly known side effects of SSRIs include weight gain, sleep changes, headache, gastrointestinal issues, drowsiness, orthostatic hypotension, and sexual function changes (1).

Sleep changes can include an increased desire to sleep, increase in the amount of time sleeping, or insomnia. Gastrointestinal issues can include an upset stomach, nausea, or dry mouth. Mood changes, such as anxiety, are possible side effects as well. Sexual function changes can include erectile dysfunction, libido changes, impaired orgasmic response, and vaginal dryness (1, 8).

There are more serious possible side effects of SSRIs as well. For instance, SSRIs have the possible side effect of QT prolongation, which if left untreated or undiagnosed, can lead to fatal cardiac arrythmias (1, 8). In particular, the SSRI citalopram has been shown to have more of a risk for QT prolongation compared to other SSRIs. Also, like any other medication that can possibly increase levels of serotonin in the body, there is a possibility of serotonin syndrome as a complication of SSRI use. Possible serotonin syndrome clinical manifestations include increased blood pressure, increased sweating, increased reflex ability, and increased dry eyes (8). Due to the wide varied range of side effects, patient counseling, monitoring, and education is essential when prescribing SSRIs.

SSRI Black Box Warning

In 2004, the FDA issued a black box warning for SSRIs and other antidepressant medications due to the possible increased risk of suicidality in pediatric and young adult populations (up to age 25). When considering SSRI use in patients under 25 and knowing MDD is a risk factor for suicidality, having a conversation with the patient about risks versus benefits must be considered. However, in the past several years since the FDA’s warning, there is no clear evidence showing a correlation between SSRIs and the increased risk of suicidality (1, 8). Health care provider professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy.

SSRI Alternatives

MDD can be a complex, chronic condition to manage with varying clinical presentation and influence on a patient’s quality of life. There are several alternatives to SSRI use, such as: (1, 9)

- Other prescription drugs

- Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Commonly known SNRIs include milnacipran, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, and levomilnacipran.

- Atypical antidepressants. Commonly known atypical antidepressants include bupropion and mirtazapine.

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Commonly known TCAs include amitriptyline, desipramine, imipramine, clomipramine, doxepin, and nortriptyline.

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Commonly known MAOIs include phenelzine, tranylcypromine, isocarboxazid, and selegiline.

- Psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal therapy

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

- Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some possible side effects of SSRIs?

- What are some pharmacological alternatives to SSRIs?

Nursing Considerations

Nurse’s Role

What Is the Nurses’ Role in SSRI Patient Education and Management?

Nurses remain the most trusted profession for a reason, and APRNs are often pillars of patient care in several health care settings. Patients turn to nurses for guidance, education, and support. While there is no specific guideline for the nurses’ role in SSRI education and management, here are some suggestions to provide quality care for patients interested in or currently taking SSRIs to manage current or suspected major depressive disorder (MDD).

- Take a detailed health history. Often times, mental health symptoms, such as depressive thoughts or anxiety, are often dismissed in health care settings, even in mental health settings. If a patient is complaining of symptoms that could be related to major depressive disorder, inquire more about that complaint. Ask about how long the symptoms have lasted, what treatments have been tried, if these symptoms interfere with their quality of life, and if anything alleviates any of these symptoms. If you feel like a patient’s complaint is not being taken seriously by other health care professionals, advocate for that patient to the best of your abilities.

- Review medication history at every encounter. Often times, in busy clinical settings, reviewing health records can be overwhelming. While a vast number of people take SSRIs, many are no longer benefiting from the medication. Ask patients how they are feeling on the medication, if their symptoms are improving, and if there are any changes to medication history.

- Ask about family history. If someone is complaining of symptoms that could be related to MDD, ask if anyone in their immediate family, such as their parent or sibling, experienced similar conditions.

- Be willing to answer questions about mental health and SSRIs. Society can often stigmatize open discussions of prescription medication and mental health. SSRIs are no exception. There are many people who do not know about the benefits and risks of SSRIs, the long-term effects of unmanaged MDD, or possible treatment options. Be willing to be honest with yourself about your comfort level discussing topics and providing education on SSRIs and MDD.

- Communicate the care plan to other staff involved for continuity of care. For several patients, MDD management often involves a team of mental health professionals, nurses, primary care specialists, pharmacies, and more. Ensure that patients’ records are up to date for ease in record sharing and continuity of care.