Course

Differential Diagnosis of Depression

Course Highlights

- In this Differential Diagnosis of Depression course, we will learn about common clinical presentations of depression, including more severe clinical presentations.

- You’ll also learn possible differential diagnosis for depression.

- You’ll leave this course with a broader understanding of recommendations for depression recovery in outpatient, non-clinical settings.

About

Contact Hours Awarded: 2

Course By:

Sadia A, MPH, MSN, WHNP-BC

Begin Now

Read Course | Complete Survey | Claim Credit

➀ Read and Learn

The following course content

Introduction

When hearing the phrase depression, what comes to mind? If you're a nurse, you've heard about depression at some point in your nursing studies and career. Maybe even before nursing school, conversations about mental health, depression, and other health conditions existed every so often.

Presently, patients seek guidance and information on various health topics from nurses, including depression and mental health. The information in this course will serve as a valuable resource for nurses of all specialties, education levels, and backgrounds to learn more about depression and differential diagnosis of depression.

Defining Depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD), more commonly known as depression, is one of the most common mental health conditions in the United States, worldwide, and a leading cause of disability.

Depression is often characterized by symptoms of a depressed mood, decreased interest in activities, changes in sleep patterns, thoughts of self-harm, psychomotor changes, and more. Given the prevalence of depression, depression is expected to be the global leading cause of disability by 2030, making depression a concern for social well-being and functioning. (1, 2, 3, 4)

What is the Prevalence of Depression?

The prevalence of depression can vary significantly because of possible underdiagnosis and mistreatment. Present prevalence rates of depression in the United States range from 5-17% with women experiencing depression at twice the rate compared to men.

Studies have suggested that the most common age of onset for depression is 40; however, more studies on adolescent, pediatric, and adult mental health suggest that this common age of onset can be much lower. Early diagnosis, intervention, and assessment are essential for prompt diagnosis and treatment (1).

Depression is also noted to be more common in people who do not have strong social support networks, those who have co-morbid conditions, and those who live in rural communities compared to urban areas (1). While several studies and interventions on depression and mood have focused on adults, pediatric and adolescent populations must also be educated and screened for depression as well (1,2).

What if Depression Is Left Untreated?

If left untreated, depression can lead to further mental health complications, suicide, disability, and further decreased quality of life. For many people with depression, depression can interfere with their abilities to maintain and form social relationships, work, and go to school as well. By leaving depression untreated or not adequately managed, depression can cause further chronic issues to someone's health and livelihood (1).

Depression Pathophysiology

There are several studies, theories, and speculations regarding depression's pathophysiology. One common factor is that depression's pathophysiology is not a one-size-fits-all, and many things can influence depression in people. Genetics, hormonal shifts, pregnancy, stress, brain injuries, side effects of other medications, co-morbid health complications, psychosocial factors, and environmental situations are all suspected to influence depression pathophysiology (1).

While several studies postulate low levels of neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, GABA, dopamine, or norepinephrine, can play a role in suicidal ideation and mental health, low levels of these neurotransmitters are not the single cause of depression. More research is being done to determine the role of neuroregulatory functions, brain functions, and neurotransmitter distribution in depression and mental health overall.

Because further research is needed to determine the exact pathophysiology of depression, it is important to consider many factors that influence depression in people (1).

Depression Etiology

Similar to depression's pathophysiology, the exact etiology and cause of depression is not known. Several studies show the role of genetics, trauma, adverse childhood events (ACEs), stress, pregnancy, and more influencing the etiology of depression. That said, because there are several etiologies of depression with more research needed, it is important to consider several options for depression etiology in direct patient care (1).

Various Types of Depression

While depression is often used as a catch-all phrase for people with a depressed mood, there are several types of depression with distinct clinical presentations, management options, and interventions as well. A common type of depression is postpartum depression, which is the most common postpartum complication in the United States and one of the most common postpartum complications worldwide.

Other types of depression include perinatal depression (depression during pregnancy), seasonal affective disorder (SAD) (depression during winter months), atypical depression, psychotic depression, and more. Because of the wide variety of clinical presentations of depression, adequate assessment, intervention, and treatment are essential for appropriate patient care (1,2).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What populations can be affected by depression?

- What are some common types of depression?

- How would you explain to a patient what can cause depression?

Differential Diagnosis for Depression

Clinical Criterium for Depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a mental health condition in which a person has consistent, prolonged appetite changes, sleep changes, psychomotor changes, decreased interest in activities, negative thoughts, suicidal thoughts, and depressed mood that interfere with a person's quality of life.

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, a patient must have at least five persistent mood-related symptoms, including depression or anhedonia, that interfere with a person's quality of life to be formally diagnosed with MDD. Other depressive states can also be assessed with the PHQ-9. Note that MDD does not include a history of manic episodes, and pediatric populations can present with more variable MDD symptoms. As a nurse, you can assess MDD by doing a detailed patient health history or having a patient complete the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (1,3,4).

The PHQ-9 is a short questionnaire that can be completed in inpatient or outpatient settings, often on an electronic device, with questions about appetite, sleep, concentration, and self-harm. Patients can rate their thoughts on these questions from not at all to nearly daily, indicating the possible severity of depression.

Since depression can also overlap with other mental health conditions, such as anxiety, schizophrenia, and chronic fatigue, it is important to also ask the patient questions about their mood, diet, sleep, and health in addition to having them complete the PHQ-9 (1,3,4).

Advanced Health Assessment Skills

Depression is such a common, chronic health condition affecting millions of people, so it can be under-recognized or misinterpreted as another health condition. When considering a formal diagnosis for depression, it is important to take a detailed patient history and also other conditions that can affect mood, such as thyroid complications, head trauma, nutritional deficiencies, electrolyte imbalances, symptom duration and onset, infection history, chronic health history, substance use, and more (1).

For instance, while a decreased interest in activities or changes in sleep patterns can be signs of depression, those can also be signs of thyroid abnormalities, Vitamin B12 deficiency, or substance use.

In addition, depressive symptoms can also be common side effects of other medications as well, such as hormonal contraception, pain medications, or antipsychotic medications. Furthermore, changes in the ability to concentrate or mood changes could be related to another mental health condition, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or bipolar disorder (1).

Key considerations for advanced health assessment skills and performing a differential diagnosis for depression include:

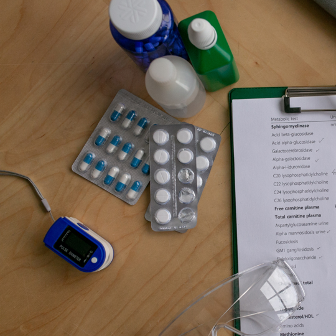

- Obtaining blood work, such as a complete metabolic panel (CMP), complete blood count (CBC), vitamin levels (specifically D and B12), iron and folate levels, and a complete thyroid panel

- Obtaining a detailed, honest patient history of substance use (including marijuana, tobacco, stimulants, and alcohol use), recent and historical trauma (sexual abuse, head trauma, car accidents), and medical history (all current and prior medication use, existing health conditions)

- Obtaining an infectious disease screening panel to include HIV, COVID-19, and syphilis

- Asking questions about mental health in general to screen for other mental health conditions, such as asking if a patient sees or hears hallucinations, has sudden mood changes, or has had any mental health concerns in the past

Upon examination and lab work result completion, it is important to consider a referral to a mental health specialist, such as a psychiatrist, mental health specializing health care provider, or therapist for a consultation. When lab work shows lab values, you can discuss these results with the patient and discuss findings of any possible health concerns (1).

Depression screening needs to be considered for every annual visit (including adult, geriatric, and pediatric patients), every pregnancy visit, and as needed. Oftentimes, in several busy healthcare settings, depression screenings are not completed or performed because of a lack of staff and lack of time. However, this results in missed opportunities for earlier intervention, detection, and management of depression and other health conditions.

If you are not comfortable with diagnosing or screening for depression, you can be honest with your patients and also refer them to specialty care as well (1).

Depression Management Options

Because of the wide clinical presentation of depression and the wide range of age groups affected by depression, there are several depression management options. From medications to therapies and lifestyle interventions, depression is a chronic health condition with several management options and more options being studied. (1, 2, 3, 4)

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What depression screenings do you use presently?

- What are some health conditions that can have similar clinical presentations of depression?

- What are some clinical labs you can use to rule out other possible causes of depressive symptoms?

Depression Recovery Paths

What Are the Options for Depression Recovery?

Depression recovery is often non-linear and complex. Many people with depression consider suicide, develop co-morbid health conditions, and report a decreased quality of life (1). Depression management options include prescription medications, therapy options, lifestyle modifications, and more. Many healthcare providers will recommend an antidepressant medication as a first-line option in addition to a therapy option, such as a referral for psychotherapy. Depending on patient presentation and response to medication, patients might need to return multiple times to manage their medication dosage, frequency, route, or new medication entirely (1,3,4,5).

In addition, medications for depression have a wide range of side effects, which is something to consider as an option for depression recovery. It is also important to educate patients that recovery from depression is often life-long and requires extensive time and effort. Oftentimes, medication alone is not enough to manage depression, and lifestyle modifications and therapies are needed as well (1).

How and Where Are Depressive Management Methods Used?

Medications for depression management are used in America and around the world in pediatric, adult, and geriatric populations. Medications can be taken by mouth as a pill, capsule, or liquid oral solution. Therapies, such as psychotherapy or group therapy, can be done in person or online depending on the mental health provider's ability. The role of telehealth has also increased access to mental health services in rural and underserved areas, making depressive management more accessible in these communities as well (1,3,4).

What Is the Average Cost of Depression Management?

Cost for depression management can significantly vary depending on the type of medications used, insurance, dosage, frequency, and other factors. Cost is among a leading reason why many patients cannot maintain their medication or therapy regime (6). If cost is a concern for your patient, consider reaching out to your local pharmacies or patient care teams to find cost effective solutions for your patients. Consider also looking into telehealth therapy options for your patients or in collaboration with your place of work as well.

Common Depression Medications

Depression has a wide variety of medication management options. Some of the most common medication management options for depression include:

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Commonly known SSRIs include sertraline, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram, escitalopram, and paroxetine.

- SSRIs are among the first line of depression medication management options and the most widely prescribed antidepressants because of their cost, medication administration route, and side effect profile.

- SSRIs have a method of action of inhibiting the reuptake pumps for serotonin, causing serotonin levels and absorption in the body to vary, causing changes in mood.

(1,3)

- Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Commonly known SNRIs include milnacipran, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, and levomilnacipran.

- SNRIs have a method of action of inhibiting the reuptake pumps for serotonin and norepinephrine, causing serotonin and norepinephrine levels and absorption in the body to vary, causing mood changes.

(1,3)

- Atypical antidepressants. Commonly known atypical antidepressants include bupropion.

- Bupropion has a method of action of inhibiting the reuptake pumps for dopamine and norepinephrine, causing dopamine and norepinephrine levels and absorption in the body to vary, causing mood changes.

(1,3)

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Commonly known TCAs include amitriptyline, desipramine, imipramine, mirtazapine, clomipramine, doxepin, and nortriptyline.

- TCAs have a method of action of inhibiting the reuptake pumps for serotonin and norepinephrine, causing serotonin and norepinephrine levels and absorption in the body to vary, causing changes in mood. (1,3)

- Because of TCAs' more serious side effect profile and incidence of toxicity, TCAs are often not a first-line medication prescribed for depression or often prescribed by providers who are not extensively knowledgeable of mental health medications.

(1,3)

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Commonly known MAOIs include phenelzine, tranylcypromine, isocarboxazid, and selegiline.

- MAOIs have a method of action of inhibiting the reuptake pumps for serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, causing serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine levels and absorption in the body to vary, causing mood changes. (1,3)

- Because of MAOI’s more serious side effect profile and incidence in toxicity, MAOIs are often not a first-line medication prescribed for depression or often prescribed by providers who are not extensively knowledgeable of mental health medications.

(1,3)

While these are among the most common types of medications for depression, most of these medications also have other indications as well, such as management for anxiety or nerve pain. It is important to consider other possible conditions a patient has that can be affected by these medications, in addition to cost, ease of access, and medication administration route.

While these medications are among the most common for depression management, they also come in various dosages. It is often recommended to start a patient on the lowest dosage possible and monitor the patient for symptom alleviation or changes. Some patients will respond well to the lowest dosage of an SSRI, while others will respond better to a higher dose of an SNRI (1,3,4,5).

When tapering a patient off of a medication to try another medication or discontinue medication therapy entirely, it is recommended to do so slowly. Patients tapering off or switching from one antidepressant to another can have severe side effects, such as serotonin syndrome, psychological changes, and physiological changes (1,3).

Because of the possibility of severe negative side effects when tapering off or stopping antidepressant medications, monitoring is essential. Before prescribing a medication, consider patient preference, other medication use, allergies, medication administration route, possible caregiver and family education, and patient overall health in determining your first possible medication option.

Common Depression Medication Side Effects

All medications have a risk of side effects, and antidepressant medications are no exception. Common medication side effects for medications for depression include weight changes, sleep changes, mood changes, headache, dry mouth, vision changes, rash, tremors, eating habit changes, and GI upset (1,7). Specific side effects of medications for depression include:

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- SSRIs have additional possible side effects of sexual dysfunction (such as vaginal dryness, erectile dysfunction, vaginal pain, decreased ability to orgasm), QTc prolongation, and jaw pain.

- Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- SNRIs have additional possible side effects of increased blood pressure, diaphoresis, and possible bone absorption.

- Atypical antidepressants

- Bupropion has a possible side effect of seizures and has a contraindication for patients with a history of seizures or suspected seizures.

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

- TCAs have additional possible side effects of urinary changes (specifically urinary retention), constipation, QRS prolongation, orthostatic hypotension, and seizures.

- It is also recommended to avoid TCAs in patients with a history of cardiovascular complications, such as heart disease, because of the risk of QRS prolongation and orthostatic hypotension.

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- MAOIs have additional possible side effects of increased potential for serotonin syndrome compared to other antidepressant medications.

In 2004, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a black box warning for SSRIs and other antidepressant medications because of the possible increased risk of suicidality in pediatric and young adult (up to age 25) populations. When considering SSRI use in patients under 25 and knowing MDD is a risk factor for suicidality, having a conversation with the patient about risks versus benefits must be considered. However, in the past several years since the FDA's warning, there is no clear evidence showing a correlation between SSRIs and the increased risk of suicidality (7). Healthcare providers’ professional discretion and patient condition should guide therapy. Consider your patient's health history and needs before prescribing any medication.

Common Depression Medication Alternatives

While prescription medications are often among the first-line options for depression management, they are often prescribed in conjunction with non-pharmacological management options. Common non-pharmacological management options for depression include psychotherapy, physical exercise, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). meditation, yoga, mindfulness exercises, over-the-counter supplements, and more (1,3).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some common medications that can be prescribed to help manage depression?

- What is the difference between SSRIs and MAOIs?

- How does cost influence someone's access and ability to manage their depressive symptoms?

Common Non-Pharmacological Depression Management Options

One of the most complementary non-pharmacological management options for depression is psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or interpersonal therapy. Given the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth psychotherapy, also known as virtual therapy, has become increasingly popular, leading to a surge of online therapy options for several age groups and populations typically hard to reach with traditional office visit times.

Patients can opt-in for psychotherapy to meet with a licensed mental health professional, such as a licensed clinical social worker or psychologist, to discuss their depressive symptoms and emotional state. Often, healthcare providers can work with therapists to determine a plan of care and monitor patients' responses to medication therapy.

In addition, while psychotherapy is often prescribed to help people with depression, therapy can also be done for families, couples, friends, and other social settings. Therapy's cost can vary by insurance, location, and provider, so if cost is a concern, that is something to address with a patient.

Physical Exercise and Depression

One of the most complementary non-pharmacological management options for depression is physical exercise, which can include walking, running, doing yoga, and performing mindful exercises. Many times, when patients (and other health care providers) hear of physical exercise, they think of someone running on a treadmill for an hour a day for a few times a week. While that is one way to do physical exercises, there are thousands of ways to do physical exercise and activity. It is important to provide realistic, evidence-based information to patients and realize that not everyone is going to go run on a treadmill for an hour every day.

Educating patients on walking in nature for 5-10 minutes a day, doing some at-home yoga for 15 minutes a few times a week with some free videos online, or taking a class once a week at a local gym are simple, straightforward steps for physical exercise. With the rise of free online fitness videos, there are multiple ways for people who are limited in time, money, or mobility to perform fitness from the comfort of their homes. While some people might enjoy physical exercise in the presence of others, other people might find more ease in fitness and exercise in a more private setting (8).

Many times, people with depression feel that physical exercise is prescribed when they might be experiencing symptoms of trouble eating, trouble concentrating, and sleeping. It is appropriate to use clinical judgment and patient-friendly language when discussing physical exercise as a possible option for helping with depressive symptoms (8).

Other Methods: ECT, VNS, TMS, OTC Supplements and Depression

Less used non-pharmacological methods to help with depression include ECT, VNS, TMS, and OTC supplements. ECT, also known as electroconvulsive therapy, is what it sounds like. ECT involves electric shocks into the brain in a healthcare setting, often in psychiatric institutions. ECT is more commonly used for seizure management but can be used for patients who have not responded to other types of depression management, for patients who are unable to take any medications, or for patients who are experiencing extreme depressive symptoms. VNS, also known as vagus nerve stimulation, is also what it sounds like. Similar to ECT, VNS uses electric shocks to the brain via vagal nerve stimulation. VNS involves electric shocks into the vagal nerve in a health care setting, often in psychiatric institutions (1).

VNS is not often a first-line option for depressive management, but it is a possible option for people who have not responded to other types of depression management, for patients who are unable to take any medications, or for patients who are experiencing extreme depressive symptoms (1).

TMS, also known as transcranial magnetic stimulation, is a type of electrical stimulation using magnets to send electrical currents throughout various parts of the brain. Similar to ECT and VNS, it is not a first-line option and uses electricity to help with brain function. TMS is a possible option for people who have not responded to other types of depression management, for patients who are unable to take any medications, or for patients who are experiencing extreme depressive symptoms. TMS involves electric shocks into the vagal nerve in a healthcare setting, often in psychiatric institutions (1).

Because of the specialized equipment and staff needed for ECT, TMS, and VNS, they are rarely used as first-line options for depressive management and are often used when other options have failed. These options are also often found in specialized psychiatric centers, which are often in major cities, presently a barrier for transportation, cost, and access for those in rural areas or with limited transportation options. Cost for ECT, TMS, and VNS can also vary significantly depending on the number of treatment sessions needed, the duration of sessions, the frequency of sessions, and patient response to these therapies (1,6).

In addition to these mechanical non-pharmacological options, there are several OTC supplements, such as magnesium and serotonin supplements, that patients can try as well. While these medications are not regulated by the FDA, for patients to limited access to health care, these are often their first-line options given their ease of access and affordability. Because of the ease of access to OTC supplements, it is important to obtain a detailed medication history prior to prescribing any medications to avoid possible complications of serotonin syndrome and medication interactions (1,6).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Why would a patient prefer to use non-pharmacological options instead of pharmacological options for depressive symptom management?

- What is the difference between ECT and VNS?

- What sort of physical exercises can be done to help with depressive symptoms?

Nursing Considerations

Nurses remain the most trusted profession for a reason, and nurses are often pillars of patient care in several healthcare settings. Patients turn to nurses for guidance, education, and support. While there are no specific guidelines for the nurses' role in depression education and management, here are some suggestions to provide quality care for patients with a current or suspected history of depression.

- Take a detailed health history. Oftentimes, mental health, such as depressive thoughts or anxiety, are often dismissed in health care settings, even in mental health settings. If a patient is complaining of symptoms that could be related to depression, inquire more about that complaint. Ask about how long the symptoms have lasted, what treatments have been tried, if these symptoms interfere with their quality of life, and if anything alleviates any of these symptoms. If you feel like a patient's complaint is not being taken seriously by other healthcare professionals, advocate for that patient to the best of your abilities.

- Review medication history at every encounter. Sometimes, in busy clinical settings, reviewing health records can be overwhelming. While millions of people take medications, many people take medications and are no longer benefiting from the medication. Ask patients how they are feeling on the medication, if their symptoms are improving, and if there are any changes to their medication history. Make sure to specify if the patient is taking any over-the-counter supplements or herbs as well.

- Ask about family history. If someone is complaining of symptoms that could be related to depression, ask if anyone in their immediate family, such as their parent or sibling, experienced similar conditions.

- Be willing to answer questions about mental health and medication use. Society stigmatizes open discussions of prescription medication and mental health. Many people do not know about the benefits and risks of depression-related medications, the long-term effects of unmanaged depression, or possible treatment options. Be willing to be honest with yourself about your comfort level discussing topics and providing education on medication and health conditions. If you are not comfortable discussing something, please refer to another staff member.

- Communicate the care plan to other staff involved for continuity of care. For several patients, depression management often involves a team of mental health professionals, nurses, primary care specialists, pharmacies, and more. Ensure that patients' records are up to date for ease in record sharing and continuity of care.

- Stay up to date on continuing education related to medications and mental health conditions, as evidence-based information is always evolving and changing. You can then present your new learnings and findings to other healthcare professionals and educate your patients with the latest information. You can learn more about the latest research on medications and mental health by following updates from evidence-based organizations.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to look at someone with the naked eye and determine if they have depression. APRNs can identify and diagnose if someone has depression by taking a complete health history, listening to patient's concerns, having patients complete the PHQ-9 questionnaire, and communicating any concerns to other health care professionals (1,3,4).

Nurses can recommend self-monitoring for patients with depression, especially regarding medication side effects. Patients should know that anyone has the possibility of experiencing side effects on antidepressant medications, just like any other medication. Patients should be aware that if they notice any changes in their mood, experience any sharp headaches, or feel like something is a concern, they should seek medical care.

Because of the social stigma associated with mental health and antidepressant use, people are hesitant to seek medical care because society has normalized side effects interfering with quality of life and fear of being dismissed by health care professionals (1,3,5). However, as more research and social movements discuss mental health and mental health medication use more openly, there is more space and awareness for medication use and mental health.

Nurses should also teach patients to advocate for their health to avoid the progression of depression and possible unwanted medication side effects. Here are important tips for patient education in the inpatient or outpatient setting.

- Tell the health care provider of any existing medical conditions or concerns (need to identify risk factors)

- Tell the health care provider of any existing lifestyle concerns, such as alcohol use, other drug use, sleeping habits, diet changes, menstrual cycle changes (need to identify lifestyle factors that can influence medication use and depression management)

- Tell the health care provider if you notice any changes in your mood, behavior, sleep, sexual health (including vaginal dryness or erectile dysfunction), or weight (possible changes that could hint at more chronic side effects of medication use)

- Tell the health care provider if you have any changes in urinary or bowel habits, such as increased or decreased urination or defecation (potential risk for medication malabsorption or possible unwanted side effects)

- Tell the nurse of health care provider if you experience any pain that increasingly becomes more severe or interferes with your quality of life

- Keep track of your mental health, medication use, and health concerns via an app, diary, or journal (self-monitoring for any changes)

- Tell the health care provider right away if you are having thoughts of hurting yourself or others (possible increased risk of suicidality is a possible side effect for medication use or worsening depressive symptoms)

- Take all prescribed medications as indicated and ask questions about medications and possible other treatment options, such as non-pharmacological options or surgeries

- Tell the health care provider if you notice any changes while taking medications or on other treatments to manage your depression (potential worsening or improving mental health situation)

What should families and caregivers know about depression?

Families and caregivers should know that depression is a chronic health condition that can require extensive medical intervention and support. Some people will need more support than others, and everyone will respond to medications differently. Because of the non-linear trajectory of depression, it is important to be realistic of your expectations when caring for someone with depression (1).

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some problems that can occur if medications are not managing major depressive disorder symptoms adequately?

- What are some possible ways you can obtain a detailed, patient-centric health history?

- What are some possible ways nurses can educate patients on medication options for depression?

Upcoming Research

There is extensive publicly available literature on depression via the National Institutes of Health and other evidence-based journals. If a patient shows interest in participating in clinical trial research, they can seek more information on clinical trials from local universities and healthcare organizations.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some reasons someone would want to enroll in depression-related clinical trials?

Conclusion

Depression management, treatment, and recovery are complex processes for people. While there are several medical interventions and guidelines, depression can vary in clinical presentation and response to therapies from person to person, making this condition extremely personalized in management, assessment, and care. Depression management is often a lifetime process that involves several medical interventions, assessments, follow-ups, appointments, therapies, medications, and people professionally and within one's social circle. Education and awareness of different management options and different clinical presentations of depression can influence the lives of many people healthily.

Case Study

Stephanie is a 32-year-old woman working as an accountant. She arrives for her annual exam at her primary care next to her place of work. She says she's been feeling more tired over the past few months. Stephanie reports having some trouble sleeping and eating but doesn't feel too stressed overall. She has a history of pre-diabetes before pregnancy, gestational diabetes during pregnancy earlier, and gave birth a few months ago.

She is currently not taking medication but was put on insulin briefly when she was giving birth a few months ago. Stephanie reports taking some over-the-counter magnesium from her local drug store, but that has not helped her sleep. She also thinks she might have some depression because she looked at some forums online and resonated with a lot of people's comments.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- What are some specific questions you'd want to ask about her mental health?

- What are health history questions you'd want to highlight?

- What lab work would you suggest performing?

Stephanie heard one of her friends talk about SSRIs for depression and wants to try them, but she's never taken prescription medications long-term before. She doesn't know if she has postpartum depression or if she's just stressed and tired of being a new mom. She agreed to complete blood work today and scored an average PHQ-9 score. She said that no one in her family talks about mental health, but she heard about depression from her friends recently and family a long time ago.

Before leaving this visit, you prescribe Stephanie sertraline 25mg once a day and want her to follow up in 6 weeks to see how she is doing. You also recommend that she see a therapist, as Stephanie reports she has never been to therapy. She denies thinking about hurting herself or others.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- How would you discuss Stephanie's mental health concerns?

- How would you explain to Susan the influence of lifestyle, such as sleep, diet, postpartum, and environment, on mood?

- What side effects would you educate Stephanie on?

- How would you educate Stephanie on self-monitoring while on a new medication?

Stephanie returns to your office three months later, and she reports that she found a good therapist online who specializes in women's health issues and has availability in the evenings. Her therapist diagnosed her with postpartum depression, and she sees her therapist weekly. Her lab work shows AIC 6 with no other abnormalities, but Stephanie is still reporting trouble sleeping and also reports pain during sex as well. She wants to know if these can be related to the serotonin changes and if there are other options for her depression.

Self Quiz

Ask yourself...

- Knowing Susan's concerns, what are some possible other pharmacological and non-pharmacological management options for her postpartum depression?

- What other specialists would you refer Stephanie to?

References + Disclaimer

- Bains N. and Abdijadid S. Major Depressive Disorder. (2023). In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559078/

- Batt M, et al. (2020). Is Postpartum Depression Different from Depression Occurring Outside of the Perinatal Period? A Review of the Evidence. Focus, 18(2), 106-119. https://focus.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.focus.20190045

- Woodall, A. and Walker, L. (2022). A guide to prescribing antidepressants in primary care. Prescriber, 33: 11-18. https://doi.org/10.1002/psb.2006

- Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R. E., Stockmann, T., Amendola, S., Hengartner, M. P., & Horowitz, M. A. (2023). The serotonin theory of depression: a systemic umbrella review of the evidence. Molecular Psychiatry, 28, 3243-3256. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

- Lam, M. K., Lam, L. T., Butler-Henderson, K., King, J., Clark, T., Slocombe, P., Dimarco, K., & Cockshaw, W. (2022). Prescribing behavior of antidepressants for depressive disorders: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 918040. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.918040

- Rohatgi, K. W., Humble, S., McQueen, A., Hunleth, J. M., Chang, S. H., Herrick, C. J., & James, A. S. (2021). Medication Adherence and Characteristics of Patients Who Spend Less on Basic Needs to Afford Medications. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM, 34(3), 561–570. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2021.03.200361

- Sheffler ZM, Patel P, Abdijadid S. Antidepressants. 2023. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): Stat Pearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538182/

- Noetel, M, et al. (2024). Effect of exercise for depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ, 384. https://www.bmj.com/content/384/bmj-2023-075847

Disclaimer:

Use of Course Content. The courses provided by NCC are based on industry knowledge and input from professional nurses, experts, practitioners, and other individuals and institutions. The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NCC. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Knowledge, procedures or insight gained from the Student in the course of taking classes provided by NCC may be used at the Student’s discretion during their course of work or otherwise in a professional capacity. The Student understands and agrees that NCC shall not be held liable for any acts, errors, advice or omissions provided by the Student based on knowledge or advice acquired by NCC. The Student is solely responsible for his/her own actions, even if information and/or education was acquired from a NCC course pertaining to that action or actions. By clicking “complete” you are agreeing to these terms of use.

➁ Complete Survey

Give us your thoughts and feedback

➂ Click the Green MARK COMPLETE Button Below

To receive your certificate